Olivia D'Aiutolo, HSP's summer 2015 Communications Intern, explores the library's cookbook collections as part of her new blog series, A Pinch of History: Culinary Commotion at HSP.

In my blog series, I will be profiling several recipes from colonial cookbooks in HSP’s collections. However, I’d like to begin with one of the largest obstacles I’ve encountered so far on my journey outside of the kitchen: the strangeness and scarcity of many recipes’ ingredients.

When asked, my friends predicted that these older dishes would be extremely simple to prepare. They would be surprised to learn that most of the dishes these women made regularly featured an extensive list of ingredients, some of which are no longer available. Other ingredients required a significant amount of additional work. Instead of a “teaspoon of nutmeg”, many of these recipes call for “one nutmeg” which would have to be ground into a powder.

Other ingredients I had never heard of before. Here’s my running list of the obscurities so far, which I’m keeping to further understand these older culinary practices.

• Marrow- flexible tissue inside bones (I looked this up because I didn’t believe anyone would cook with marrow… I soon learned it’s common practice today for bone broth)

• Fricassee- when meat is cut, sautéed, braised, served in sauce it was cooked in

• Sweetmeat- candy covered in sugar; “meat” just meant food, something to eat

• Mace- covering of nutmeg shell

• Collop- slice of meat

• Pippin- red/yellow dessert apple

• Lamprey- jawless fish with tunnel-like sucking mouth (looks unappetizing… take my word for it)

• Sack- fortified wine

• Florentine- usually when spinach is included in a recipe

• Syllabub- dairy dessert made from cream & wine; served cold

• Posset- frothy custard made from cream, wine, eggs; served hot

• Treacle- uncrystallized syrup made during sugar refinement

• Suet- raw beef or mutton fat

• Tansy- flowering herbaceous plant (several books had recipes featuring flowers)

• Indian meal- cornmeal

• Pearl ash- first chemical leavening used in baking

• Emptins- yeast from the remnants of the beer brewing process

• Quinces- fruit in the apple & pear family

• Musk- aromatic substance from animal glands like deer

• Rusk- hard and dry biscuit or twice-baked bread

• Rosewater- rose petals steeped in water, used to flavor food

Have any of you come across these ingredients in your culinary adventures, past or present?

I am going to do my best to obtain mace and rosewater, as a lot of the baking and dessert recipes I’ve selected call for them. I’m trying my hardest not to compromise the integrity of the recipe, hoping to convey utmost authenticity of colonial cuisine through my blog.

Most of the dishes consumed during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in America had a European taste, with the majority brought over from the Old World. Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery contains recipes dating back to Elizabethan England. As time went on, recipes began evolving, incorporating the different materials and foodstuffs available in the New World that Europeans did not previously have access to.

Many items now considered staples would have looked unfamiliar to the Old World’s emigrants. Europe didn’t have corn, potatoes, squash, tomatoes or turkey.

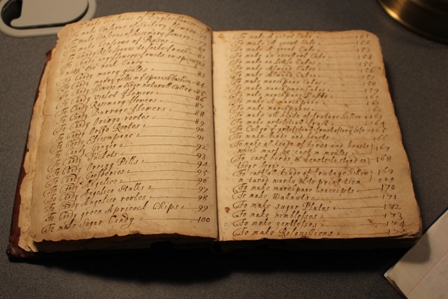

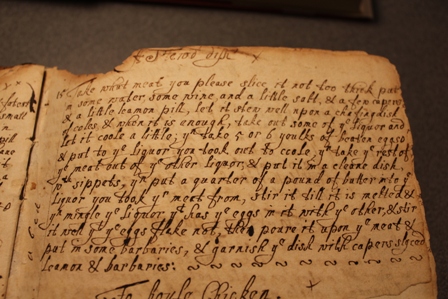

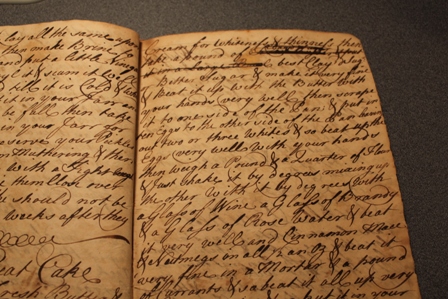

I would also like to comment on the cookbooks themselves, as physical objects. Martha Washington’s and Mary Plumstead’s recipe books are handwritten; they seem more like personal family artifacts meant to be passed down through generations than something stuffed away in a kitchen. In the case of Martha’s cookbook, it was in fact an heirloom passed down to her by the mother-in-law of her first husband (George was her second husband). While reading through these cookbooks, I had the feeling of being a part of their family.

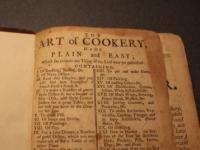

Hannah Glasse’s and Amelia Simmons’s books, on the other hand, are printed books with forwards and introductions. Glasse said she wrote the book to simplify the cooking process for the servile class while Simmons is known for the first cookbook published in America featuring exclusively American ingredients in several of the recipes. These were easier to read but were still written in a style entirely different from any common cookbook. Glasse and Simmons both devoted a significant amount of time explaining how to choose the best ingredients and cook with respect for seasonality.

I couldn’t help but feel connected to these women as I paged through their work. I know how difficult it can be to run a kitchen, as I normally cook every night in my house. I also began, over the last few months, developing my own recipes rather than using ones I have found. It is difficult to get recipes right the first time. I wasn’t concerned with the lack of specific measurements of most ingredients, as that is how I would cook. It is so much more enjoyable when you are not concerned with measuring this or that, but rather just working through the process and experiencing it. Throw in however much is needed to make the food taste good!