by Beth Kreydatus

This article was published in the fall 2018 issue of Pennsylvania Legacies (vol. 18, no 2): Protest in 1960s Pennsylvania.

On September 7, 1968, two protests took place within blocks of one another on the boardwalk of Atlantic City, New Jersey, both giving voice to the growing disgust many Americans felt for the Miss America Pageant. One demonstration was led by the New York Radical Women (NYRW), one of the earliest women’s liberation groups, and was attended by roughly 100 women, including Carol Hanisch, Robin Morgan, Flo Kennedy, and Jo Freeman—activists with a history of engagement in the Civil Rights and New Left movements and leaders of the burgeoning women’s liberation movement. The second protest was sponsored by two black men from nearby Philadelphia: J. Morris Anderson, a black businessman, and Phillip H. Savage, a local NAACP official. Anderson and Savage organized and staged a Miss Black America counter-pageant, which incorporated elements of the Miss America tradition but pointedly imbued them with black pride and the politics of respectability. Both protests, and the media coverage that followed them, helped to shape and focus the opposition to an annual tradition that many Americans believed to be degrading to women.

“Trail-Breaking Beauties of Yesteryear: These eight girls helped start the Atlantic City Beauty Pageant rolling away back in September, 1921.” Philadelphia Record, Aug. 30, 1948. Philadelphia Record Photograph Morgue.

The Miss America pageant was a potent symbol for activists wishing to reshape American culture. Begun in 1921 as an “Inter-City Beauty” contest, the pageant was, by 1968, an entrenched national institution. Playing before 25,000 live audience members and on the television screens of as many as 27 million viewers; it regularly ranked as either the first- or second-most popular broadcast in the nation. Year after year, Bert Parks serenaded pageant winners with “There She Is, Miss America,” calling her “the queen of femininity” and “your ideal.”

Miss America reflected and, arguably, shaped American gender norms. The young women who vied for the crown were vigorously screened for sexual “respectability”—required to be unmarried, chaperoned, and abstinent from alcohol, cigarettes, and, especially, sex. Any whiff of “moral turpitude” could disqualify a woman from the contest. So could her race. In the 1940s, contest rules explicitly required that contestants be “of the white race.” While the official language mandating whiteness disappeared in the 1950s, African American women were excluded until 1970. Furthermore, candidates faced class barriers. The pageant was an expensive affair for which contestants had to don multiple wardrobes, including ballgowns. Finally, contestants were expected to quietly support the political status quo. For example, Judith Anne Ford (Miss America 1969), when asked her opinion about the protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, demurred, “That’s controversial. . . . I hate to talk about this.” As her interviewer, New York Times reporter Charlotte Curtis, pointed out, this “is what Miss Americas are supposed to say.” Overall, the pageant sent the message that the ideal American woman was white, wealthy, virginal, and apolitical.

In 1968, protesters hoped that critiquing Miss America might result in meaningful cultural change. Women’s liberationists objected primarily to the ways in which the pageant objectified women. Pointing to the swimsuit contest, a central part of the pageant wherein the judges explicitly assessed contestants’ bodies, the protestors compared the human contestants to “cattle” and the pageant to an “auction block.” However, they also hoped to make a point about several other causes, including antiracism, anticommercialism, and antiwar activism. As organizer Robin Morgan explained, the Miss America pageant “has always been a lily-white, racist contest; the winner tours Vietnam, entertaining the troops as a ‘Murder Mascot’; the whole gimmick is one commercial shillgame to sell the sponsor’s products. Where else could one find such a perfect combination of American values—racism, militarism, sexism—all packaged in one ‘ideal symbol,’ a woman.” Historians consider the Miss America pageant protest they staged on September 7, 1968, to be the first demonstration of second-wave feminism, and the protest and the media portrayal of the protesters shaped the public image of women’s liberation for decades thereafter.

Swimsuit-clad contestants of the Miss America pageant “raise their tootsies in salute to Philadelphia,” Sept. 1, 1941. Philadelphia Record Photograph Morgue.

In contrast, black activists from Philadelphia, a city that had a strong black power movement by the late 1960s, focused on the exclusionary racism of the pageant. Historian Georgia Paige Welch has written about the regional opposition to the all-white pageant in the journal Feminist Formations. She explains that in 1966, Atlantic City NAACP activists had threatened boycott to integrate the pre-pageant parade; in subsequent years, the Afro American Unity Movement challenged police brutality and the neglect of black neighborhoods in Atlantic City, hinting that without reform, they’d protest outside of the pageant. Many African American residents of Atlantic City, a strictly segregated tourist town that catered to white tourists, chafed at hosting an annual pageant that celebrated white womanhood and deliberately excluded blacks.

Officially, the NAACP had embraced a slow-but-steady push for integrating the pageant. During the summer of 1968, the Atlantic City chapter of the NAACP had worked with the Miss America organization to appoint an African American reverend to its board of directors and begun recruiting African Americans to participate in local and state contests. But that same summer, Philadelphians J. Morris Anderson and Philip Savage demanded immediate attention to the issue, announcing a separate Miss Black America pageant. Because Savage was the leader of the New York-Delaware-New Jersey NAACP branch, the pair’s announcement seemed to carry the sanction of the NAACP, although the organization was never actually involved. Instead, Savage worked with Anderson, a former stockbroker and publisher who devoted his business acumen to developing and sustaining the pageant. When introducing plans for Miss Black America to the press, Savage explained “We want to be in Atlantic City at the same the hypocritical Miss America contest is being held. Theirs will be lily white and ours will be black.” He went on to charge the Miss America organization with “reinforcing a false and hypocritical sense of racial awareness in its viewers.” Savage and Anderson believed that black Americans were being sold the message that only white women were beautiful, and they turned to a pageant of their own to recognize black women’s beauty.

The Miss Black America pageant was prominently staged in front of the Convention Center hosting the all-white Miss America event. Contestants participated in a parade along the Atlantic City Boardwalk and a cabana party on the beach. Savage and Anderson imbued the event with symbols of Black culture. The Newark (NJ) Sunday News reported that “Bongo players in Africa garb provided the music . . . as Miss Black America contestants rode down the boardwalk in a motorcade and then through the Negro neighborhood.” By choosing 19-year-old Saundra Williams of Philadelphia as the winner, pageant organizers drove home the black pride message. A junior at Maryland State College majoring in sociology, Williams was active in campus civil rights activism and had organized a “Black Awareness Movement” at her school. She sported a natural hairstyle and told reporters, “With my title, I can show black women that they too are beautiful, even though they do have large noses and thick lips.” She won the pageant by performing an African dance and a monologue entitled “I am Black.” Media reports hinted at connections between the newly crowned Miss Black America and the burgeoning black power movement.

Portrait of Saundra Williams, Miss Black America 1968, in In Black America—1968: The Year of Awakening, ed. Patricia W. Romero (New York, 1969).

Miss Black America grew in popularity. The original pageant featured 10 contestants and was attended by only about 200 spectators. In 1969, however, the pageant had as many as 4,300 people in the audience; was judged by black activists, including Betty Shabazz, widow of the late Malcolm X, Shirley Chisholm, the first black US Congresswoman, and Floyd McKissick, former chairman of CORE; and featured performances by Stevie Wonder and the Jackson Five.

In early years, Miss Black America enabled activists to draw symbolic attention to Miss America’s racist exclusivity. Savage and Anderson’s protest was embedded with some internal contradictions, however. First, was an NAACP official endorsing a “separatist” approach to racial justice? At a time when black activists disagreed whether separatism or integration was the more appropriate path to equality, there was some controversy in establishing an all-black event, even to protest an all-white one. Secondly, the Miss Black America pageant, organized by two men, appeared to fully embrace the gender politics of the original. The female contestants were explicitly judged for their appearance and decorum, and while the winner, Saundra Williams, criticized men for not helping with household responsibilities in an interview with the New York Times, the pageant itself did little to question patriarchal culture. When the Times reporter asked Williams about the women’s liberation protest, Williams purportedly “looked bored.” Miss Black America contestants were expected to advance black rights by emphasizing their respectability. Challenging gender norms would not be compatible with this political approach.

While Savage and Anderson clearly rebuked the Miss America pageant for its racism, it did so by creating a duplicate event that embraced many of its elements, including profits from ticket sales and advertising. The directors confronted the contradictions of running an activist pageant that mimicked white, patriarchal, capitalist pageantry when Joyce Warner (Miss Black America 1971) refused to attend the 1972 pageant, alleging she’d been exploited “to make financial gains for a few individuals who claim to be working in the best interests of black people.” Her comments suggest that not all black women embraced a second, black-centric pageant as the best approach to activism. Nevertheless, Miss Black America has continued annually since 1968. It was aired as a telecast by 1969 and made it to primetime NBC by 1977.

The women’s liberationists employed a different form of pageantry—the spectacle of opposition. The style of the women’s liberation demonstration borrowed from Civil Rights, New Left, and antiwar protests. In an action reminiscent of burning draft cards, feminists submitted permits to the Mayor of Atlantic City to burn “women garbage,” including bras, girdles, curlers, high-heeled shoes, and other “instruments of torture to women.” Because the permits were denied, activists merely threw these items into a “freedom trash can”—nevertheless, the myth of the “bra-burners” was born. African American lawyer and activist Flo Kennedy and Bonnie Allen, another black feminist, pretending to be chained to a maypole, participated in a staged “cattle auction,” while Peggy Dobbins, a white member of the New York Radical Women, played auctioneer, reading off their attributes to the crowd. Both in this action, and in a flyer advertising the demonstration headlined “Slavery Exists!” feminists echoed the language and imagery of black nationalists and the civil rights movement. The protestors unfurled a banner proclaiming “Women’s Liberation” in the Atlantic City Convention Center just as the outgoing Miss America made a televised farewell speech. As promised in the “No More Miss America!” pamphlet distributed by the NYRW, the protest was a “day-long boardwalk-theater event.”

“200 years of bondage is enough!” announces this undated National Organization for Women (NOW) brochure promoting the Equal Rights Amendment. National Organization for Women, Philadelphia Chapter Records.

The women’s liberation protest was met with mockery from many critics. On the boardwalk, a small counterprotest developed, including a former beauty queen wearing a sign painted, “There’s Only One Thing Wrong With Miss America. She’s Beautiful.” Crowd of passersby screamed insults, calling the women’s liberationists communists and lesbians. Members of the news media continued to deride the protestors over the following days and months. New York Post editorialist Harriet Van Horne, for example, lashed out, “If they can’t be pretty, dammit, they can at least be quiet!”

Even some participants wondered whether their rhetoric was effective. Organizer Carol Hanisch questioned the effectiveness of signs reading “Miss America Sells It” and “Miss America is a Big Falsie.” Worrying that these signs were divisive or even “anti-womanist,” she insisted that future protests needed to more clearly delineate criticism of the pageant as an institution from criticism of the women who participated in it. As she explained in 2000, the “main point in the demonstration [was] that all women were hurt by beauty competition—Miss America as well as ourselves.” Hanisch’s critique of the pageant illustrates the challenge of contesting normative gender expectations and the cultural institutions that perpetuate them without seeming to criticize the individuals—especially the women—who live and strive within these norms.

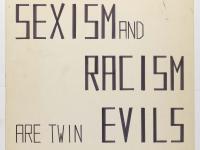

Journalists and historians alike have emphasized the two Miss America protests’ differences, suggesting that there was little common ground between women’s liberation and Miss Black America organizers and emphasizing the divisions between these two groups. Certainly, dealing with double oppression—sexism and racism—has complicated African American women’s participation in both black and feminist organizations. It’s likely that the Miss Black America pageant would have benefited from black female leadership, and the women’s liberation movement should have done more to include and prioritize black women’s voices. Georgia Paige Welch has argued, however, that the two protests actually shared more common ground than historians and journalists have acknowledged: the activists in both cases were responding to a shared set of concerns, working with a shared set of symbols, and meeting with similar (negative) media coverage. Welch pays particular attention to the neglect of Flo Kennedy’s role in the protest. As a black activist with roots in both civil rights and black power movements, Kennedy’s leadership at that demonstration makes it harder to suggest that the two protests were strictly divided by race.

“Sexism and Racism Are Twin Evils of Society” poster, undated. National Organization for Women, Philadelphia Chapter Records.

The Miss Black America pageant, still helmed by J. Morris Anderson, continues in 2018, recently celebrating its 50th anniversary with a pageant in Kansas City. The Miss America pageant has grown more racially diverse in the past 50 years, yet the crowning of the first Indian American winner (Nina Davuluri, Miss America 2014) was met with racist and xenophobic hostility on social media. And after emails surfaced in December 2017 showing that Miss America CEO Sam Haskell and pageant telecast lead writer Lewis Friedman had used derogatory language to refer to past winners, the pageant moved to all-female leadership for the first time in its history with the appointment of CEO Regina Hopper and Board of Trustees Director Gretchen Carlson. Carlson and Hopper’s leadership seemed particularly significant at a time when the #MeToo movement against sexual harassment was first gaining steam. In June 2018, Carlson announced a radical shift in the pageant away from evaluation of contestants for their appearance towards emphasis on interviews and talent. These changes—including the elimination of the swimsuit competition—have led to open revolt from dozens of state and local leaders, and the organization appears to be deeply divided about the pageant’s future. It remains to be seen whether the Miss America pageant can survive as a talent contest that de-emphasizes appearance. Meanwhile, the Miss Black America leadership has responded to calls for an end to their own swimsuit pageant with a firm refusal. Clearly, after 50 years, many of the concerns raised by protestors in 1968 continue to be significant and deeply divisive.

Beth Kreydatus is an associate professor in the Department of Focused Inquiry at Virginia Commonwealth University. She teaches general education courses, with a focus on service-learning.

This article was published in the fall 2018 issue of Pennsylvania Legacies (vol. 18, no 2): Protest in 1960s Pennsylvania. Learn more and subscribe.