By Cameron L. Kline

Colonial Tobias Lear V (1762-1816) penned the only first-hand accounts of the death of George Washington in December of 1799. He was at Mount Vernon helping his friend and mentor, the first President of the United States, by being “…engaged in writing letters, recording military papers…” when he witnessed the death of our young nation’s greatest leader (Lear, Tobias Lear Diary, 1799-1801).

Lear’s relationship with Washington began in 1785 when Washington went searching for a secretary. Washington was still an active citizen on the young nation’s stage and was flooded with correspondence and requests. He reached out to his friend, Major General Benjamin Lincoln, for help. Lincoln, who later became the namesake of Lear’s son, recommended Tobias Lear, a 23-year-old family friend. Washington wrote:

"I have at last found a Mr. Lear, who supports the character of a gentleman and a [Harvard] scholar. He was educated at Cambridge, Mass. He has been to Europe and in different parts of this continent. It is said he is a good master of languages. He reads French and writes exceedingly good letters." (Brighton, 1985, p. 33)

Lear’s primary duties were to help the former President with his voluminous correspondences, the hosting of guests, and the day-to-day activities of Mount Vernon from 1784 until Washington’s death in 1799. Mount Vernon’s floors were well trodden by the near-great and great. From Adams, Jefferson, and Madison to friends, family, craftsmen, and merchants to his army colleagues and masonic brothers, everyone wanted to spend time at Mount Vernon. Lear was a secretary, he was a gopher, he was a mentee, and he was the man behind the man who helped Washington run his plantation, eventually becoming a dependable secretary and gatekeeper in the Office of the First President of the United States.

In August of 1795, Lear married Martha Washington’s favorite niece Fanny. As a wedding present, George Washington gave Lear, his wife, and her three children—to live on but not to own—a house and 360 acres of his Mount Vernon estate. Lear and his family were close to Mount Vernon, he regularly spent time at the house, and so on Thursday, December 12, 1799, he wrote:

"…[T]he general rode out to his farms about ten o’clock, and did not return home till past three. Soon after he went out the weather became very bad, rain, hail and snow falling alternately with a cold wind.

I observed to him that I was afraid he had got wet; he said no, his great coat had kept him dry; but his neck appeared to be wet and the snow was hanging upon his hair. He came to dinner (which had been waiting for him) without changing his dress. In the evening he appeared as well as usual."

An infection, today considered to be acute bacterial epiglottitis, took hold. Between 2 and 3 a.m. on Saturday, December 14, 1799, Washington, who was bedridden, concluded that he is dying:

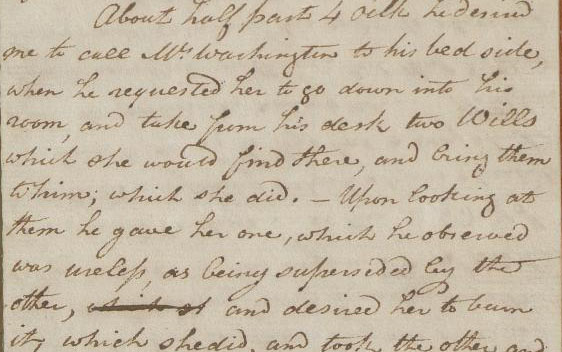

"About half past 4 o’clock he desired me to call Mrs. Washington to his bed side, when he requested her to go down into his room, and take from his desk two Wills which she would find there, and bring them to him; which she did. Upon looking at them he gave her one, which he observed was useless, as being superseded by that other, and desired her to burn it, which she did, and took the other and put it into her closet.After this was done, I returned to his bed side and took his hand. He said to me, 'I find I am going.'"

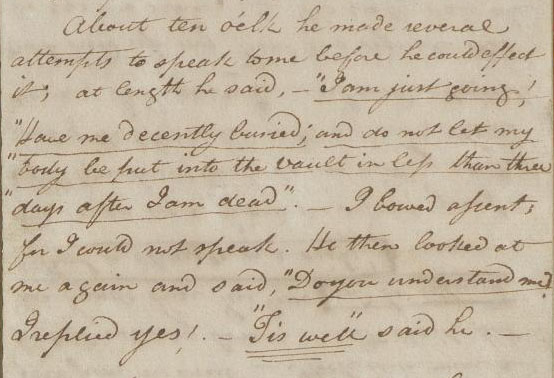

Washington, who could barely speak at this point and was in great pain, was close to death but was still focused on sharing his last wishes:

"'Have me decently buried; and do not let my body be put into the vault in less than three days after I am dead.' I bowed assent; for I could not speak. He then looked at me again and said, 'Do you understand me?' I replied yes! 'Tis well' said he."

The Tobias Lear journal, which is housed in the archives of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, documents the period of time from December 10, 1799 to July 4, 1801. It is 70 pages long, with interspersed blank pages. It details the death of Washington, records the President’s final wishes, funeral perpetrations, funeral (December 18, 1799), entombment, the possible publishing of his papers, love for his family, Lear’s appointment to be Council to St. Domingo (March 29, 1801), a Caribbean journey, and the journey’s weather reports.

Read the full account with Washington’s last words. Transcription by Cameron L. Kline.

See the original journal in HSP's Digital Library.

Related Materials

References

Brighton, R. (1985). The Checkered Career of Tobias Lear. Portsmouth, NH: Portsmouth Marine Society.

Lear, T. (1799-1801). Tobias Lear Diary. Tobias Lear Diary, Historical Society of Pennsylvania (Am.09238), Dec. 10, 1799.