On May 5, 1829, while digging in the Durham section of the Delaware Canal in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, contractors Porter & Hough uncovered a remarkable burial. Beneath three feet of earth, a “pile of 18 cannon balls was found, and directly underneath, the bones of a human being.” As can be imagined, such a discovery gained a significant amount of public attention, as reported in a number of local newspapers, including an account published in The Ariel, a Philadelphia periodical of the time.

Excavations of the Delaware Canal had begun as early as October of 1827 in Durham Township and continued periodically through 1830. That specific area of Durham was the site of the Durham Iron Works, which was built in 1848. Prior to that, Durham Township was home to the Durham Furnace, which predated the American Revolution. The forge produced cannon and shot in great numbers during the war.

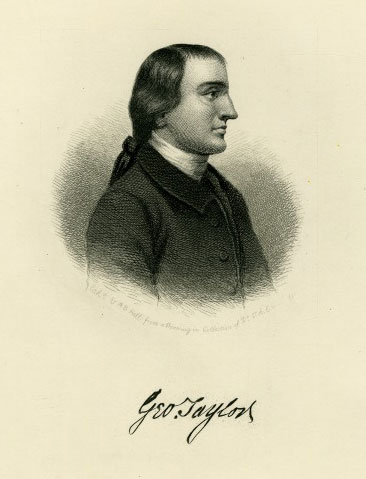

Irish-born George Taylor, an ironmaster, militia colonel, member of the Continen tal Congress, and one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, served as a superintendent of the Bucks County furnace. While living at Durham, he is given credit for being the first person in Pennsylvania to “make shot and shells for the Continental Army” from 1775 through 1778, as revealed in a number of early Pennsylvania colonial records.

tal Congress, and one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, served as a superintendent of the Bucks County furnace. While living at Durham, he is given credit for being the first person in Pennsylvania to “make shot and shells for the Continental Army” from 1775 through 1778, as revealed in a number of early Pennsylvania colonial records.

In October of 1775, Taylor was producing 18-, 24-, and 32-pound cannonballs in significant numbers. As late as August of 1782, the Durham Furnace shipped 12,357 “solid shot” to Philadelphia by boat.

The mysterious 1829 discovery raises many questions. Who was the person buried there? Why did he have eighteen cannonballs lying on top of his remains? It was a common practice for centuries to drive a stake through the body of a deceased criminal after internment or weigh down a body after death, in an attempt to prohibit its spirit from rising up from the grave and haunt the living. Whether this was the case with the man found in 1829 will no doubt never be known.

There are surviving accounts of both British and German prisoners of war who had been impressed into hard labor at the furnace during the administration of Richard Backhouse. Some of these men became sick during their imprisonment. Perhaps one of these men perished during the Revolution and was buried at the site, with cannonballs placed upon his remains, for the reason mentioned above. This is one of many interesting archaeological discoveries throughout the Philadelphia area, ones that cry out for an interpretation. Perhaps a reader of this sketch may find the answer.