When one thinks of early Quakers or members of the Society of Friends, a common stereotype is that they were predominately pacifists, or non-aggressive in nature. Though this may be true to a large degree, like individuals of all faiths, there are those who fail to fit the prescribed behavior and instead exhibit characteristics quite distinct and independent of the norm. Born in 1799, Josiah Harlan, a Quaker from Chester County, Pennsylvania, was one such character.

As early as 1826, Harlan was firmly entrenched within the political and military conflicts transpiring between India and Afghanistan. In 1838-39 he was the Aide-de-Camp to Dost Mohammed Khan, the Emir of Kabul and in command of a division of the Afghan army whom he trained in European-style warfare. It is believed that Rudyard Kipling’s famous short story, The Man Who Would be King, was based in part upon the life and experiences of Harlan while he resided in the border area of the Punjab in India and what is now Afghanistan. Harlan aligned himself for awhile with the native ethnic group known as the Hazaras, who agreed to declare him the Prince of Ghor, an Afghan province.

Map of Cabul [Kabul] and the Vicinity by General Harlan

When the British army arrived upon the scene in the 1830s, Harlan was very critical of its policies in general and had no amiable relations with its forces or military personnel. Though he had resided within the northern regions of the Indian subcontinent for some eighteen years, he eventually returned to Philadelphia. Here his father, Joshua Harlan, had worked as a broker merchant.

For sometime Harlan became involved in a variety of ventures, from grape agent to mill operator, and attempted to introduce camels as transportation animals within the armed forces. In 1855, Jefferson Davis (then Secretary of War for the United States, later the President of the Confederate States of America during the Civil War) allocated $30,000 dollars to purchase camels for American forces to be used in the Southwest. Harlan advocated the camels be obtained from Afghanistan while the U.S. government opted for those from Africa. Regardless, the American Camel Corps was short-lived.

After the outbreak of the Civil War, Harlan raised the 108th regiment, also known as Harlan’s Light Cavalry. He was eventually commissioned as a Colonel in the Union army, but was forced to retire because of ill health on August 20, 1862. Prior to this, in 1849, he married Elizabeth Baker, also a Quaker from Chester County, by which he had one child.

Harlan later obtained employment as a physician, after he’d made another geographical move, this time to San Francisco. There he would die of tuberculosis on October 21, 1871.

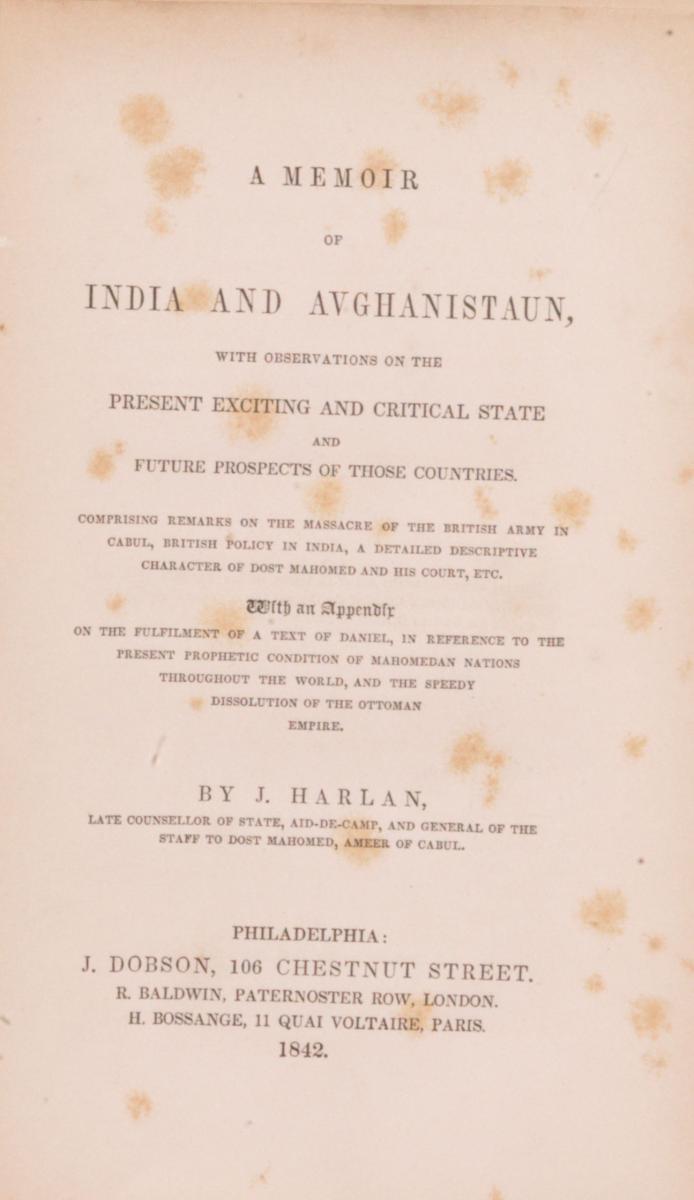

A few years ago Harlan was the subject of a biography by British author Ben Macintyre, titled, The Man Who Would be King: The First American in Afghanistan (2004). Harlan was an established author as well, and one can read his work, A Memoir of India and Avghanistaun… (Philadelphia: J. Dobson, 1842), at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Harlan also wrote Personal Narrative of General Harlan’s Eighteen Years’ Residence in Asia, a manuscript that was never published. Truly “truth is stranger than fiction,” and much of this truth is available within the collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.

A few years ago Harlan was the subject of a biography by British author Ben Macintyre, titled, The Man Who Would be King: The First American in Afghanistan (2004). Harlan was an established author as well, and one can read his work, A Memoir of India and Avghanistaun… (Philadelphia: J. Dobson, 1842), at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Harlan also wrote Personal Narrative of General Harlan’s Eighteen Years’ Residence in Asia, a manuscript that was never published. Truly “truth is stranger than fiction,” and much of this truth is available within the collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia.