Some people assume that the magical practice of using a likeness of a person to influence his actions or destiny is a product of Haitian or West African Vodou or Voodooism. Yet such paranormal acts are not exclusively African in origin. Image Magic, or invultuation or envoutement as it is officially known, has been around for centuries in many countries. In European folk traditions, clay, wood, metal, and wax all have been used to make life-like images of individuals. Purportedly, the victim will suffer torment or pine away as the doll is stabbed, drowned, burnt, or tortured in some way.

According to a Latin work known as the Laws of Henry I, invultuation (along with poisoning, sorcery, and other forms of black magic) was considered to be murder as early as the twelfth century. In 1538, “a wax baby with two pins stuck in it” was discovered in a London churchyard. A man who was knowledgeable about sorcery declared that the maker of the puppet “was not his craft’s master, for he should have put it either in horse dung or in a dung hill.” As late as 1916, a woman showed a County Sussex vicar in England a “rude figure cut out of a turnip,” which contained “two pins stuck into that part which represented the chest” purportedly made by her husband in order to afflict her.

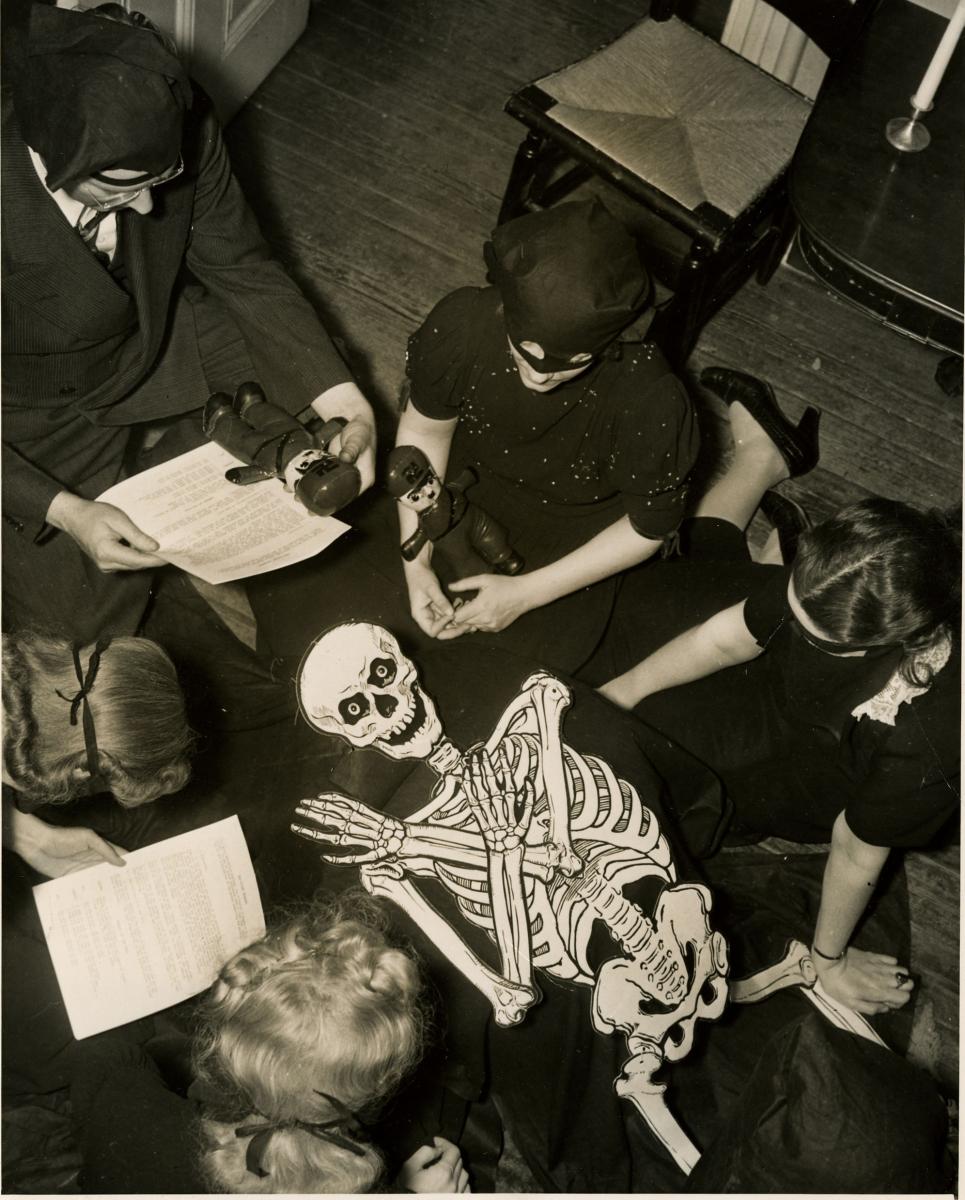

It is not surprising then that during World War II, supernatural customs that were still prevalent in Europe were used to afflict nefarious characters such as Adolf Hitler with disease or death. These photographs, found within the Philadelphia Record photo morgue at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, reveal that the belief in “image magic” persisted at that time.

Europe were used to afflict nefarious characters such as Adolf Hitler with disease or death. These photographs, found within the Philadelphia Record photo morgue at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, reveal that the belief in “image magic” persisted at that time.

In February of 1941, residents of Central Europe and immigrants from that area residing in Washington, D.C., called upon the old pagan deity of Istan (akin to the Magyar or Hungarian word Istvan  for god) to invoke his wrath to effect Hitler’s demise. Illustrations and even cardboard cutouts of a skeletal figure representing Hitler, along with wooden dolls, were stuck with pins in vital organs in the belief that the mass murderer would thus suffer destruction.

for god) to invoke his wrath to effect Hitler’s demise. Illustrations and even cardboard cutouts of a skeletal figure representing Hitler, along with wooden dolls, were stuck with pins in vital organs in the belief that the mass murderer would thus suffer destruction.

As can be seen in the image at beginning of this article, a cat (often perceived as an animal connected to witchcraft) invokes its inherent powers upon “a doll-image of Adolf Hitler” by leaping onto an altar to examine the pin-pierced figure at weekly hex-related meetings.

The collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania abound with modern imagery of a centuries-old custom, along with other supernatural-related materials. Perhaps these items will entice to you make a research trip to the Historical Society this Halloween, if you dare!