Once or twice, upon forgetting to do homework in grade school, I considered telling my teacher that I conscientiously objected to the assignment. It sounds a lot better than "The dog ate my homework." But if I was a student at Westtown School, with its storied Quaker heritage, and my teacher actually had been a Conscientious Objector during World War II, I would definitely stick with the "dog ate it" excuse.

Westtown School in Chester County, Pennsylvania is the oldest continuously operating coeducational boarding school in the United States. It was founded by the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in 1799 with the goal of educating Quaker children in an environment that fostered moral development consistent with their religious ideals. The school's archives are extensive, encompassing not only the records of the school administration, but also collections of personal papers gathered from various alumni, teachers, and other individuals associated with the school.

Among these collections is the papers of J. (John) Bernard Haviland (1915-2004), a Westtown alumnus who also taught English and Bible there for several decades. He was an active member of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) who served Philadelphia Yearly Meeting on their Standing Committee on Spiritual Life, wrote widely on Quaker topics, and registered as a Conscientious Objector during World War II. The J. Bernard Haviland papers, 1929-1998, consist of files created by Haviland while a student at Princeton (1930s), a teacher at Westtown School (1940s-1960s), a graduate student at Harvard University (1940s) and at University College, Dublin (1960s), and notes for courses he taught at Pendle Hill.

Among these collections is the papers of J. (John) Bernard Haviland (1915-2004), a Westtown alumnus who also taught English and Bible there for several decades. He was an active member of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) who served Philadelphia Yearly Meeting on their Standing Committee on Spiritual Life, wrote widely on Quaker topics, and registered as a Conscientious Objector during World War II. The J. Bernard Haviland papers, 1929-1998, consist of files created by Haviland while a student at Princeton (1930s), a teacher at Westtown School (1940s-1960s), a graduate student at Harvard University (1940s) and at University College, Dublin (1960s), and notes for courses he taught at Pendle Hill.

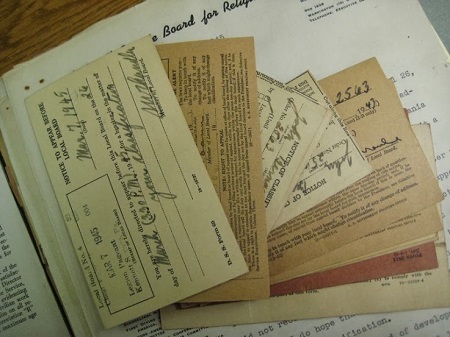

Of particular interest to me in the Haviland papers were materials relating to Haviland's status as a Conscientious Objector (CO) during World War II, including his applications and appeals; informational flyers/materials from Friends groups about CO status; articles about Haviland on pacifism and Conscientious Objection; and correspondence with his father and others about Conscientious Objection.

During World War I, CO status was granted to individuals who could prove membership in an Historic Peace Church--principally the Mennonites, Church of the Brethren, and Religious Society of Friends. The CO application process had become more nuanced by World War II, with CO status granted to individuals who could convincingly demonstrate their objection was by "by reason of religious training and belief" (section 5(g) of the Burke-Wadsworth Act of 1940), even if they were not part of a pacifist sect. Haviland explained in his CO application, "I believe that within every man there is some knowledge of the Will of God as well as the ability to do God's Will if he so chooses. I believe that men are potential brothers in the presence of the common knowledge of God's Will and that the realization of this potential brotherhood is the object of God's Will."

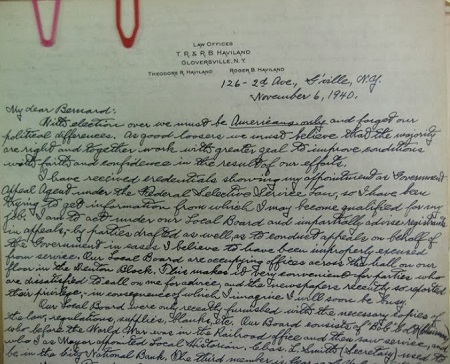

Perhaps in preparing his application Haviland consulted with his father, who was a Government Appeal Agent under the Federal Selective Service Law. Several of his letters, including this one a scant month before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, cast light onto the experience of determining legitimate claims to conscientious objector status.

"I am to act under our Local Board and impartially advise registrants in appeals,-by parties drafted as well, as to conduct appeals on behalf of the Government in cases I believe to have been improperly excused from service."

Whether or not he consulted with his father, Haviland's application essays were likely more sophisticated and articulate than most received by the draft boards. At the time a budding scholar of Quaker religion, Haviland wrote several articles about theological topics related to pacifism and about moral integrity and the military.

If I had been Haviland's student and claimed conscientious objection to a homework assignment, perhaps he would have just smiled and asked me to instead fill out a multi-page application explaining why, by reason of religious training and belief, I felt conscientiously opposed to participation in homework in any form. Should have blamed it on the dog.