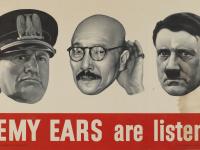

Last month, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania highlighted our Japanese Internment manuscript materials of WWII with “The Truth Behind Hold These Truths,” a program featuring Penn professor Dr. Franklin Odo, a performance by Makato Hirano, and a discussion with Sumiko Kobayashi, a former internee whose records are housed at the Society. Over 120,000 individuals of Japanese ancestry were incarcerated during that period of American history, with roughly 77,000 actually holding American citizenship. But many are unaware that other ethnic groups residing with the United States, including American citizens of both Italian and German ancestry, were also incarcerated during both the First and Second World Wars. The Federal government and many citizens-at-large were afraid that perhaps some of these individuals were not only sympathetic but actively plotting covert operations on behalf of the Axis Powers of Mussolini and Adolf Hitler against the Allied forces. Incarceration during times of war,however, is nothing new in U.S.history. During the first two years of the Civil War, it is estimated that President Lincoln approved the arrest of approximately 13,000 American citizens by declaring martial law and suspending the right of habeus corpus. These presidential directives affected those persons generally referred to as Peace Democrats. These were pro-Southern individuals believed to be overtly thwarting the Lincoln administration’s war effort via vocal condemnation within the press or covert military funding and recruitment for the seceded Confederate States of America.

Such concerns were also expressed during the First World War when Theodore Roosevelt expressed his disgust for what he referred to as “hyphenated Americanism.” “A hyphenated American is not an American at all…The only man who is a good American is the man who is an American and nothing else.” German-Americans were often referred to in the press as hypens and it was suggested in Iowa in April of 1918 that there were “5,000 persons… who ought to be in the stockade this very minute…the nest egg of all treason in the United States is the German press and the German language.” Others remarked that such ostracism would cause division in America, with “one against another… this awful war should not be made more terrible by internecine strife.” Some 2,000 Germans would be incarcerated at Fort Douglas, Utah, and Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia.

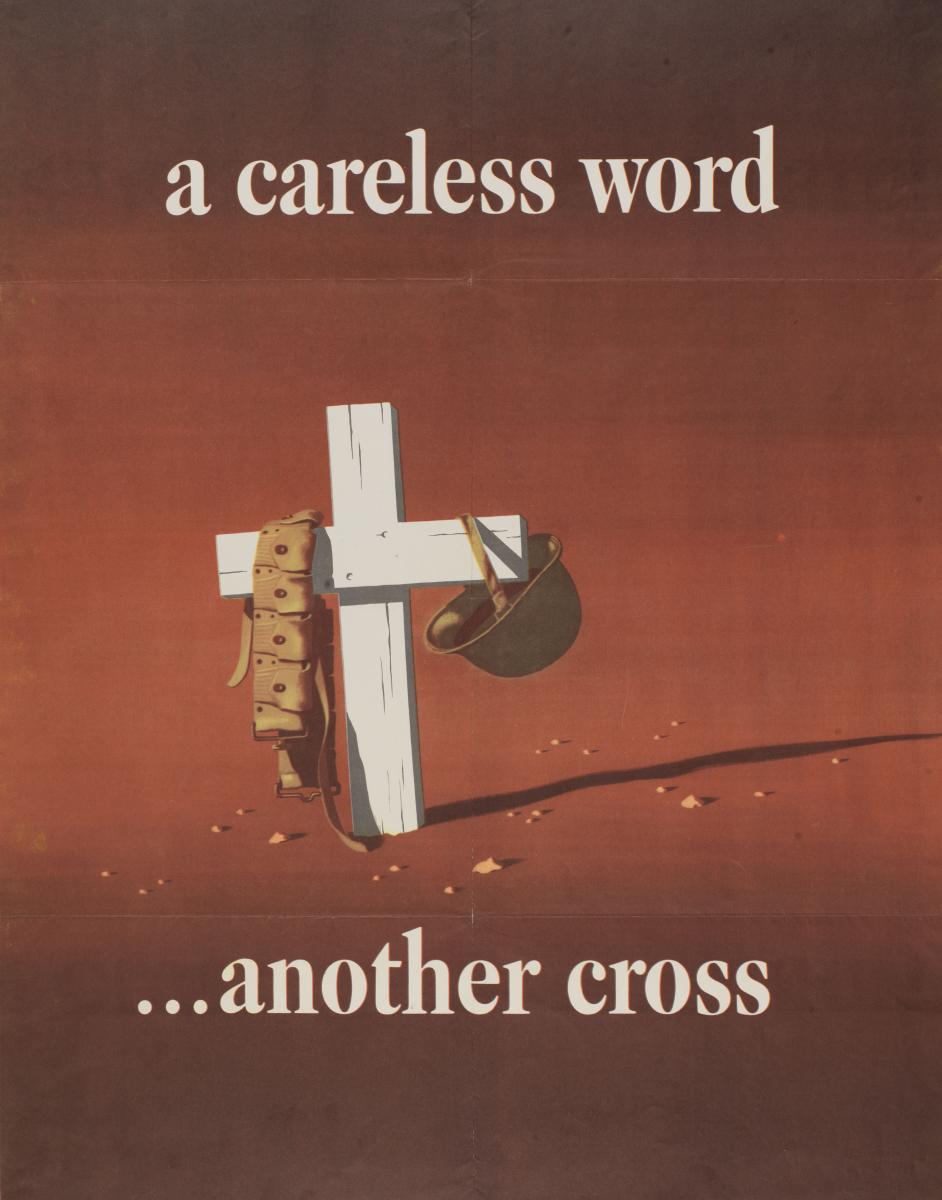

During the Second World War the U.S. government detained over 11,507 Germans and 1,521 Italian aliens. Japanese-Americans were forced to sell their businesses, remove from the West Coast to the East, or were incarcerated. Despite these obstacles, the famous 442nd Infantry Division, composed primarily of Japanese-Americans, earned more purple-hearts for valor fighting the Nazis in Europe than any other military organization.

Though there were a few cases of American citizens aiding the enemy, most so-called hypenated Americans were very loyal to their adopted country. The late Gordon K. Hirabayashi, a former internee, would later remark how he had believed that the Constitution had failed him. But “with the reversal in the courts...I feel that our country has proven that the Constitution is worth upholding. The U.S. government admitted it made a mistake. A country that can do that is a strong country. I have more faith and allegiance to the Constitution that I ever had before.”

Though there were a few cases of American citizens aiding the enemy, most so-called hypenated Americans were very loyal to their adopted country. The late Gordon K. Hirabayashi, a former internee, would later remark how he had believed that the Constitution had failed him. But “with the reversal in the courts...I feel that our country has proven that the Constitution is worth upholding. The U.S. government admitted it made a mistake. A country that can do that is a strong country. I have more faith and allegiance to the Constitution that I ever had before.”