It will perhaps come as no shock that, in terms of website categories, pornography attracts the most traffic. Number two, however, may surprise some: genealogy.

Popularized by shows such as Who Do You Think You Are? and Finding Your Roots, genealogy - the study of lines of descent - has become one of the most prevalent pastimes in the United States.

Broadly speaking, interest in one's family - alive and dead - is represented in every human society. However, its expression differs throughout time and space. Like its European and Asian forebears, the historical and modern practice of genealogy in the United States reflects its peoples' shifting priorities and paranoia. Tracing the tree of genealogy itself offers a roots-deep insight into American culture.

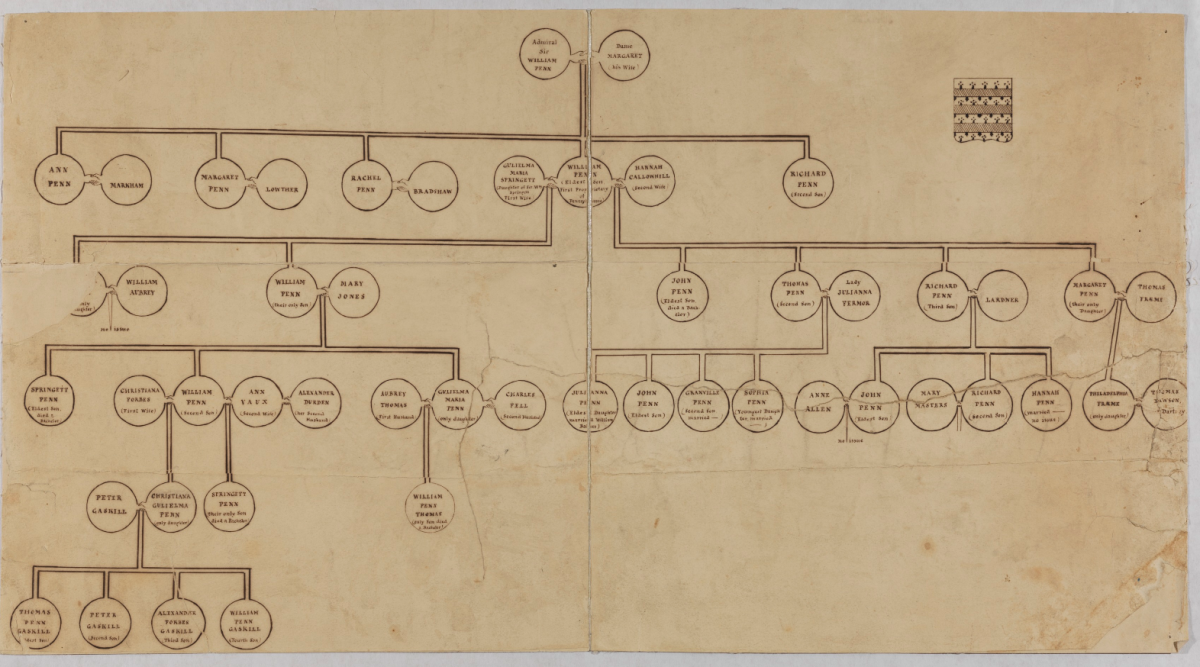

The Penn family’s genealogy chart (William and Hannah are in the second level, in the middle). From the Historical Society of Pennsylvania Genealogy Chart Collection.

The British fondness for royal and aristocratic pedigrees had long been exported to their colonies, whose settlers sought to establish social status within the empire by tracing their lineage - and inheritance - to landed families in England and Scotland.

Aside from these baronetcy-chasers, other colonists expressed a more private attentiveness to their family history. The margins of Bibles, typically a family's most precious possession and passed down generationally, were often filled with details of members' lives. With church registers far from comprehensive, these notes also represented a practical solution to documenting births, deaths, and marriages.

Modern genealogists will commiserate with their 18th-century counterparts upon hearing of their identical challenges. Henry Laurens, a president of the Continental Congress, lamented that his father "had been very Careless concerning his Ancestry," saving few family records, which "account[s] for the deficiency of my knowledge in the history of our past Generations."

After a bloody eight-year war waged against the tyranny of ancestral privilege, it is perhaps no surprise that the class consciousness of the colonial era's "gentry genealogy" became unfashionable among newly minted republicans.

Yet, by 1856, an English visitor to the United States observed that "the number of family records or genealogical monographs [was] much larger in America than in aristocratic England." What happened?

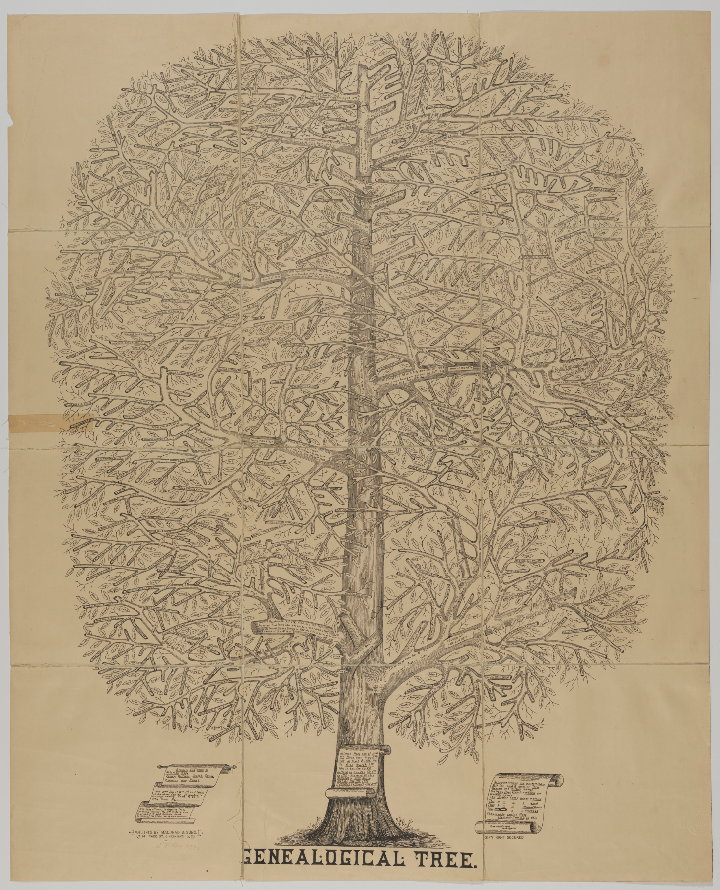

The Hoge family tree. From the Historical Society of Pennsylvania Genealogy Chart Collection.

Like the United States, genealogy itself was democratized. Stripped of its status-seeking connotations and redefined as a civic, if not moral, responsibility, an interest in one's ancestors was no longer solely the pastime of social climbers or hidden away in family Bibles. It was part of a wave of historical consciousness sweeping the nation. This newfound reverence for the past - hitherto a decidedly un-American trait - produced many of the nation's earliest historical societies and genealogical organizations, including the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1824.

"There often is . . . a regard for ancestry which nourishes only a weak pride," acknowledged Daniel Webster in an 1820 address at Plymouth, but "there is also a moral and philosophical respect for our ancestors, which elevates the character and improves the heart."

With this democratization came commercialization. So popular was genealogy in antebellum America that publishers of Bibles began to preprint blank pages for family members' jottings, while printers hawked memorial lithographs and researchers-for-hire offered to travel and copy records.

Not all were convinced of this new middle-class pastime. "When I talk with a genealogist, I seem to sit up with a corpse," Ralph Waldo Emerson spat in 1855.

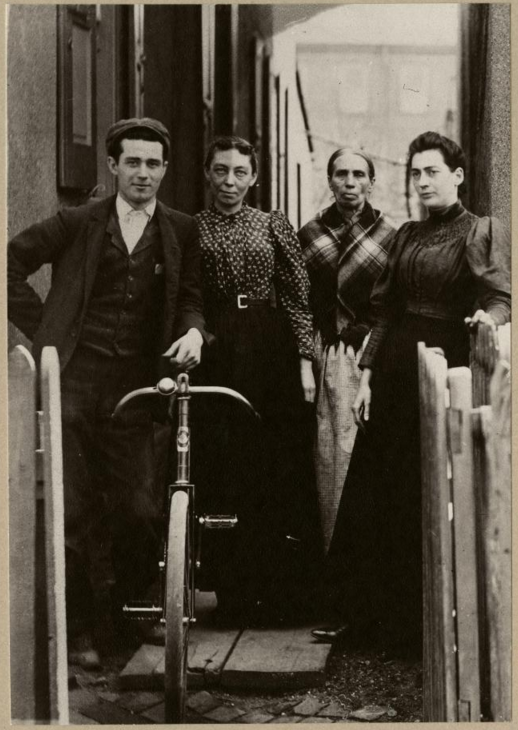

Photograph of William Magee with his mother Mary Louise Campbell Magee, and sisters. From the Historical Society of Pennsylvania Magee Family Photograph collection [PG141].

From Reconstruction through the Second World War, several forces upended American society. The onslaught of industrialization and increased immigration from Ireland, Italy, Greece, and China challenged traditional notions of race and class. The works of Charles Darwin and Gregor Mendel put the issue of heredity at the forefront of Americans' concepts of identity and group membership.

Popular genealogy adopted this racial perspective, minimizing its historical and moral aims and becoming a handmaiden for eugenics. Genealogists' methodology and sources became a means to document the "purity" of the Anglo-Saxon race, a way to distinguish these "uncorrupted" lineages from those of the Caucasian but otherwise non-WASP immigrants.

The global conflagrations brought about by racial patriotism and eugenics in the 1930s and 1940s shook these shibboleths, with the 1960s civil rights movement further discrediting them.

"Genealogical trees do not flourish among slaves," observed Frederick Douglass in 1855. Court records and fugitive narratives tell a more nuanced story - of relatives sought through the Freedmen's Bureau during Reconstruction, of genealogy preserved and transmitted orally - and it is the legacy of slavery as experienced by one family that kicked off genealogy's modern resurgence: Alex Haley's 1976 novel, Roots.

35mm group portrait of the Ahonkhiaf family circa 2000. From the Historical Society of Pennsylvania New Immigrants Initiative collection [3442].

With the advent of the Internet and the accessibility of millions of records online, genealogy has become a multicultural pursuit within the reach of most Americans. What does current interest in genealogy say about contemporary culture, of individual and collective identities, of our orientation to the past, to the future? Now, as before, genealogy often reveals more about the genealogists than their ancestors.

On March 18 and 19, HSP is hosting Family History Days, one of the Mid-Atlantic's largest genealogy conferences, for beginners and experienced genealogists alike. Learn more at hsp.org/FHD.

This article originally appeared in the February 28, 2016, Currents section of the Philadelphia Inquirer as part of its weekly series, Memory Stream.