Imagine taking an afternoon stroll through a meticulously sculpted garden, winding along pathways lined with flowers and shrubberies overlooking majestic view of the Schuylkill River. Detailed sculptures are scattered along the path, depicting cherubs and angels. You pass stelae and obelisks, and as you continue, you find yourself surrounded by elaborate mausoleums. Not only are the stone structures beautiful works of art, decorated with detailed carvings and Tiffany stained glass windows, but they also serve as the final resting place for the deceased.

For many today, taking such an afternoon jaunt through a graveyard is not an ideal way to spend your time. However, for Philadelphians in the nineteenth century, sightseeing, picnics, and strolls among the dead were not out of the ordinary. Death was a common part of everyday life in the Victorian era, and infant and child mortality rates were high. Victorian Philadelphians had what many today might label as a morbid fascination with the dead, and this celebration of the deceased can easily be observed at Laurel Hill Cemetery.

Located in what is now the East Falls neighborhood of Philadelphia, Laurel Hill Cemetery was founded in 1836 by John Jay Smith as an alternative to the relatively small, crowded cemeteries of the inner city. Situated on a large plot outside of the city along the Schuylkill River, Laurel Hill Cemetery was envisioned as a picturesque setting: Curving paths, gardens, terraces, and sculptures created a romantic landscape, with burial spaces for the dead in a restful and tranquil setting.

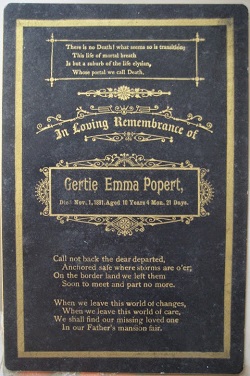

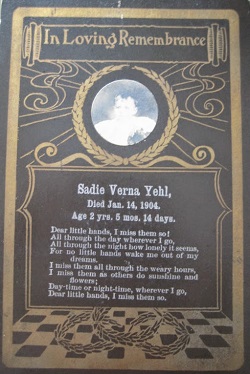

The influence of Victorian sentiment towards the dead can clearly be discerned in the landscape of Laurel Hill, as well as in the elaborate gravesites, from the decadent mausoleums on Millionaire’s Row to the towering obelisks with detailed engravings. This commemoration of the deceased was not limited to the art of the burial site, but also included a fascination with post-mortem photography and mourning cards.

With the introduction of the daguerreotype, photographs of the deceased could be produced at a much lower cost that commissioning a portrait of memorialization. With the high mortality rates among babies and children, it is no surprise that post-mortem photographs of the deceased young were regularly commissioned, and that many can be found in the archival collections at Laurel Hill Cemetery.

Along with photographs of the deceased, one can find mourning cards. Wealthier families could afford larger embossed cards and could sometimes include a post-mortem photograph inserted.

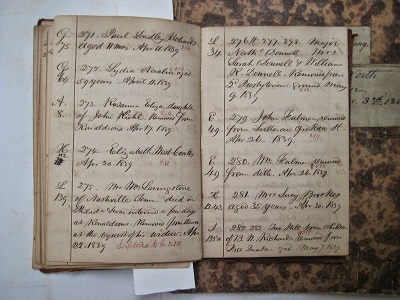

Although it is hard to imagine so for a cemetery, the records of Laurel Hill also contain somewhat less morbid materials, such as reports to the Board of Public Health recording the cause of death for those interred at the Cemetery and scenic photographs of lots and views found in the Cemetery. Visit Laurel Hill Cemetery yourself and see what you can find!

Pages from the earliest interment records from Laurel Hill Cemetery.

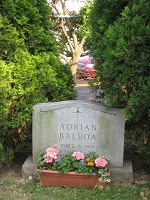

And while you’re there, you can stop by and say to some of the notable residents of Laurel Hill, including Harry Kalas, General George Meade, and Adrian Balboa.