Historians generally agree that French aid was instrumental to the American victory during the Revolutionary war. Officers such as the famous Marquis de Lafayette and Viscount Francois-Louis Teissedre de Fleury to the countless numbers of enlisted men, all helped the Colonies gain their independence.

However, another patriot from France, Major William Galvan, has been all but forgotten in most published accounts of the Revolution. He is a man of mystery in many ways as revealed by his death in Philadelphia during the summer of 1782. He received a commission in the Continental Army on January 12, 1780, eventually serving in General Lafayette’s personal command.

Orders were eventually issued to Galvan on May 16, 1780, directing him to Cape Henry, Virginia where he’d deliver dispatches to the Admiral of the French fleet. Thomas Jefferson was asked by George Washington to provide Galvan with lodging and boats, and to keep the French volunteer apprised of military operations within the Southern colonies.

Throughout his service, Galvan would rub shoulders with many famous Revolutionary officers – including General von Steuben and Mad Anthony Wayne. At times, he was not particularly in favor with the troops placed under his command, and on occasion, a suggestion was made to relieve him of his duties since he was said to be very unpopular with certain officers. However, he appears to have redeemed himself by his actions during the battle of Green Spring, Virginia, on July 6th, 1781. During a brief but seminal skirmish, British forces – which included such famed officers as Lord Cornwallis and Banastre Tarleton - met American units near Jamestown Island and Powhatan Creek. Though not an outstanding military victory for America, it nonetheless boosted morale for the cause and revealed the fact that the infamous British dragoons were not invincible as many believed.

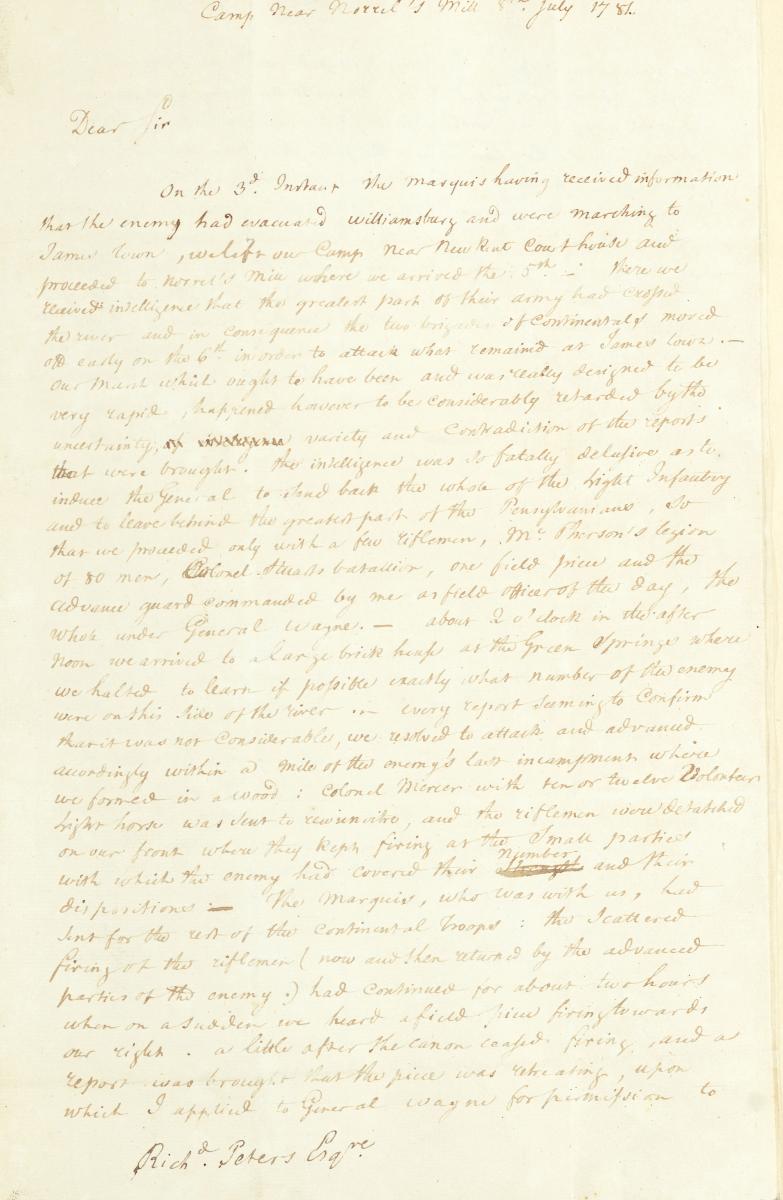

Galvan’s detailed account of the skirmish and his involvement (no doubt somewhat inflated), is contained within a lengthy letter dated July 8th, 1781, to Richard Peters, as found within the Anthony Wayne Papers housed here at the Society. Gen. Anthony Wayne gave Galvan permission to attempt the capture of a British field-piece (or cannon) during the outset of the skirmish with a battalion of Continental infantry, which brought the Frenchman and his forces in the direct fire of the enemy for fifteen minutes. Though Lafayette and Wayne’s later accounts cast their blunder as a victory, no blame was attached to Galvan. Rather he and his unit were praised. As the Pennsylvania Journal , Pennsylvania Gazette, along with Gen. Lafayette himself would state: “The brilliant conduct of Major Galvan and the Continental detachment under his command entitle them to applause.”

Galvan’s detailed account of the skirmish and his involvement (no doubt somewhat inflated), is contained within a lengthy letter dated July 8th, 1781, to Richard Peters, as found within the Anthony Wayne Papers housed here at the Society. Gen. Anthony Wayne gave Galvan permission to attempt the capture of a British field-piece (or cannon) during the outset of the skirmish with a battalion of Continental infantry, which brought the Frenchman and his forces in the direct fire of the enemy for fifteen minutes. Though Lafayette and Wayne’s later accounts cast their blunder as a victory, no blame was attached to Galvan. Rather he and his unit were praised. As the Pennsylvania Journal , Pennsylvania Gazette, along with Gen. Lafayette himself would state: “The brilliant conduct of Major Galvan and the Continental detachment under his command entitle them to applause.”

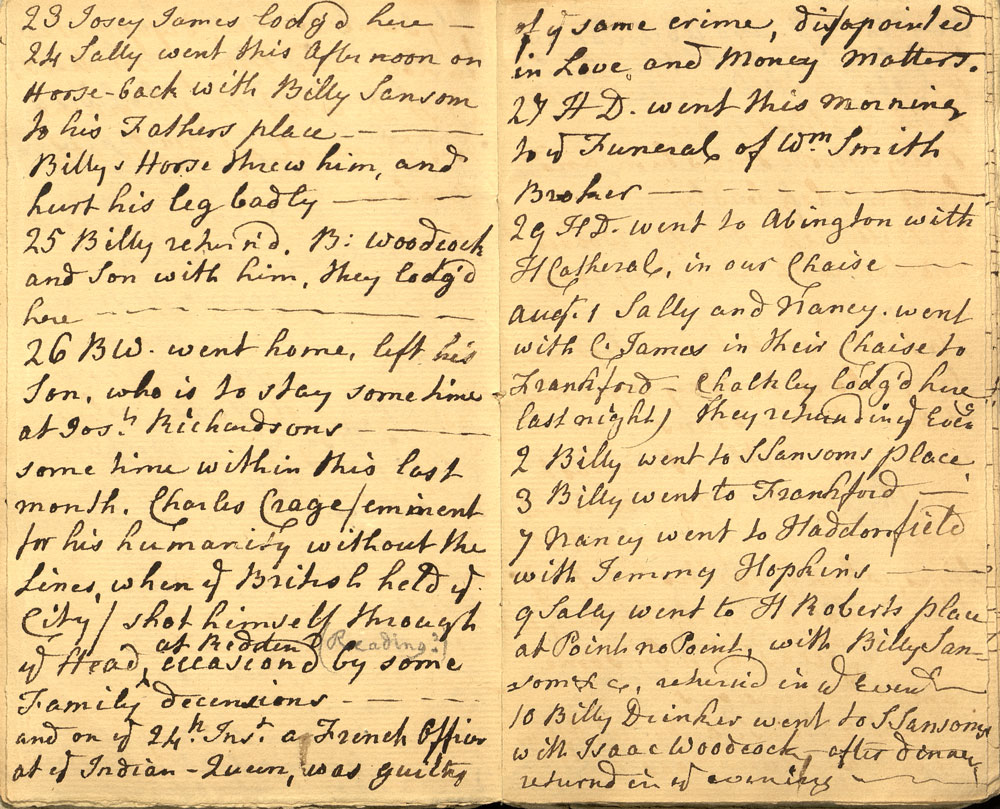

By July 24th, 1782, Major William Galvan was dead. Not by a British bul let, but by his own hand. Famed Quaker Elizabeth Drinker, speaking of the death of an individual by suicide in a diary entry for July 26th, also remarked how, “on the 24th. Instant a French Officer at the Indian-Queen, was guilty of the same crime, disappointed in Love, and Money Matters.” Jacob Hiltzheimer, a German immigrant who later became a Representative in the Philadelphia Assembly, gave more details in his diary entry for July 25th, stating, “Returning from a ride with my wife, saw the burial of Major Galvan in the Potter’s Field. The Major shot himself last night through the head.”

let, but by his own hand. Famed Quaker Elizabeth Drinker, speaking of the death of an individual by suicide in a diary entry for July 26th, also remarked how, “on the 24th. Instant a French Officer at the Indian-Queen, was guilty of the same crime, disappointed in Love, and Money Matters.” Jacob Hiltzheimer, a German immigrant who later became a Representative in the Philadelphia Assembly, gave more details in his diary entry for July 25th, stating, “Returning from a ride with my wife, saw the burial of Major Galvan in the Potter’s Field. The Major shot himself last night through the head.”

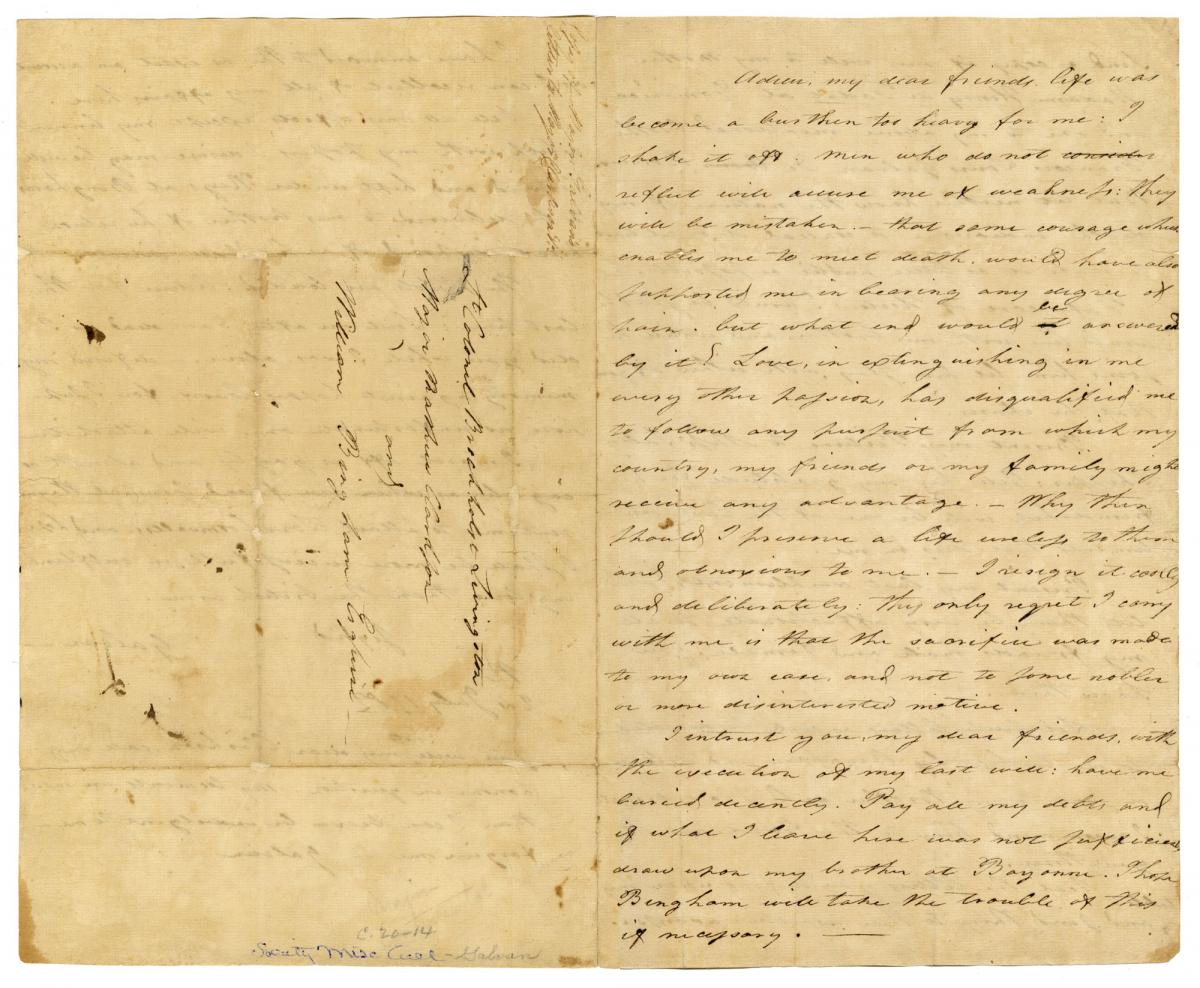

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania possesses Major Galvan’s suicide note. addressed to Lt. Col. Brockholst Livingston, Major Matthew Clarkson and William Bingham. Galvan states how, “…life has become a burthen {burden} too heavy for me: I shake it off. Men who do not reflect will accuse me of weakness: they will be mistaken. That same courage which enables me to meet death, would have also supported me in bearing any degree of pain…” The natural question arises: why did a famed officer kill himself?

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania possesses Major Galvan’s suicide note. addressed to Lt. Col. Brockholst Livingston, Major Matthew Clarkson and William Bingham. Galvan states how, “…life has become a burthen {burden} too heavy for me: I shake it off. Men who do not reflect will accuse me of weakness: they will be mistaken. That same courage which enables me to meet death, would have also supported me in bearing any degree of pain…” The natural question arises: why did a famed officer kill himself?

Within Galvan’s suicide note, he asked that a picture of himself be presented “to Miss Sally Shippen: Tell her my gratitude for her friendship will be one of the last sentiments that dies in me.” Sally was no doubt Sarah Shippen (1756-1831), the daughter of Judge Edward Shippen and Sarah Plumley of Philadelphia, whose home, during the occupation of the city by British troops, was frequently visited by various English officers. No doubt similar visits transpired by American military officials like Galvan after the departure of the British. Sarah would eventually marry Thomas Lea on September 21st, 1787. Galvan certainly had money troubles, and though he asks to be “buried decently,” he ended up in Potter’s Field, now Washington Square. He also asked for all his debts to be paid, and a copy of his will to be sent to his mother, Madam Henry de Fadat at Dominica, and one to his brother, Francois Louis Galvan De Bernoux, living at Bayonne. Yet no will appears to have survived, at least in Philadelphia probate records, nor were his wishes carried out, perhaps for lack of funds.

One would naturally think that Lafayette or some other French or even American official would have been willing to pay the young Frenchman’s debts, yet many native-born Americans soldiers, even several signers of the Declaration of Independence, were never reimbursed for their acts of service. Therefore, sadly, it may not be too surprising that Galvan’s last wishes went unfulfilled.

The mystery surrounding Galvan's death also extended to the War Department as late as 1795. In the Statement on the account of William Galvan it's recorded that his exact date of death could not be determined. It's interesting to note that the answer to that question lies in other sources at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. One wonders what else may be found in the archives.