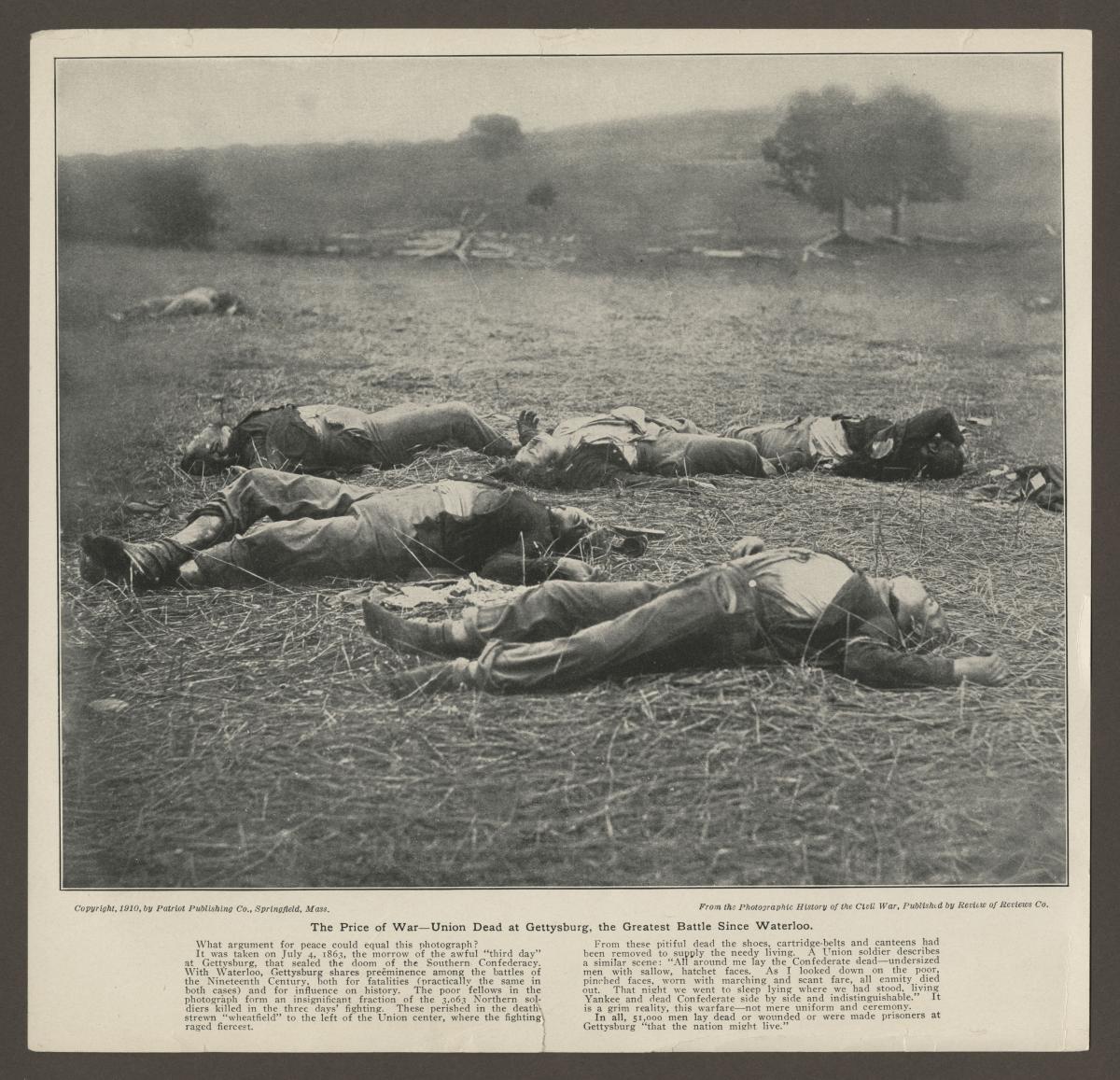

At least seven thousand men lost their lives during the famous ‘Battle of Gettysburg,’ fought from July 1–3 in 1863 in Pennsylvania during the Civil War. For quite some time, this author has been researching the elegies or mournful poetic tributes appearing in Philadelphia newspapers, in regard to soldiers of the Philadelphia Brigade, more specifically the Seventy-Second Infantry Regiment,  which had forty-six members killed and numerous others wounded on July 3, 1863, during the aforementioned battle. Most of these individuals were volunteer firemen, known as the Fire Zouaves (formed by Col. De Witt Clinton Baxter), and referred to collectively as ‘Baxter’s Philadelphia Fire Zouaves.’ However, this tragedy was not restricted nor limited only to soldiers who perished, but also to civilians after the conflict was over, one in particular being the father of a deceased soldier of the ‘Fire Zouaves’ of Philadelphia.

which had forty-six members killed and numerous others wounded on July 3, 1863, during the aforementioned battle. Most of these individuals were volunteer firemen, known as the Fire Zouaves (formed by Col. De Witt Clinton Baxter), and referred to collectively as ‘Baxter’s Philadelphia Fire Zouaves.’ However, this tragedy was not restricted nor limited only to soldiers who perished, but also to civilians after the conflict was over, one in particular being the father of a deceased soldier of the ‘Fire Zouaves’ of Philadelphia.

The Philadelphia Public Ledger for July 15, 1863, speaks of GEORGE ELMER BRIGGS, of Co. ‘G’ of the Seventy-Second, losing his life “on the 3rd…son of Russell and Rachel Briggs…Buried on the battlefield.” Census records of the period reveal that RUSSELL M., was a “moulder,” residing with his family within the Spring Garden section of Philadelphia, on Callowhill Street. The elder Briggs had specifically traveled to Gettysburg in November of ’63,’ in order to hear the speeches delivered by famed orator, Edward Everett (1794-1865), and Pres. Abraham Lincoln, on Thursday, November 19 (from which the famous ‘Gettysburg Address’ would derive) in regard to the ‘consecration of the National Cemetery,’ but also to “remove the remains of his son killed in the battle,” according to a variety of newspapers published at the time.

The United States Marshall of the District of Columbia, and close friend of Pres. Lincoln, Mr. Ward Hill Lamon, acted as the ‘Chief Marshal of the day’ during the Gettysburg ceremonies. Prior to his departure back to Washington, D.C., newspapers remark how on Friday, November 20th, Russell M. Briggs {though some erroneously report his name as “Williams”}, “had with him a coffin at the front door of the house…the dead body of his own son who was killed in the battle…” and that the “whole of Marshal Lamon’s party had just passed the spot where the explosion took place…within thirty feet of the shell when it exploded...,” being present when a young boy named boy Allen Frazer, with a loaded shell in his hands, had it taken from him by Mr. Briggs, who immediately “took it and attempted to remove the charge with a file. The terrible missile exploded in the man’s hands, blowing them both clean off several inches above the wrists,” the boy being instantly killed and “horribly mangled.”

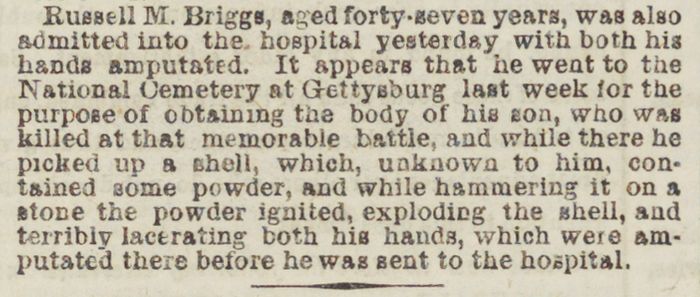

The Philadelphia Press, Daily Age, North American and other city newspapers, relate that “Russell M. Briggs” not long after the incident occurred, was taken to the ‘United States Hospital at Camp Letterman’ in Gettysburg, where “the amputations were immediately performed by Dr’s. Stonelake and Chamberlain,” and that he was eventually moved to the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia. Briggs was described as “doing well,” though he had also had his “right eye,” arm, and ankle injured as well during the accident.

Some accounts give the incident as transpiring at the residence of Mr. Solomon Powers in Gettysburg, a member of the ‘Committee of Eight,’ which had specifically been organized to “procure a suitable lot in the cemetery” at Gettysburg for the burial of the soldiers. Allen Frazer, the son of Thomas F. and Elizabeth Frazer, is also mentioned repeatedly within contemporary accounts, as being the young boy who also perished during the shell’s explosion. He was only fourteen years of age, an orphan “living with Mr. Powers,” and while standing near Briggs, had a fragment of the shell cut him “nearly in two…,” his remains being interred in the Evergreen Cemetery at Gettysburg.

After the famed battle, the New York Times on November 20 mentioned how “the smell of decaying bodies saturated large portions of the 50 square miles around Gettysburg,” while “relic hunters immediately became a problem; people would stumble on unexploded ordnance and set it off, resulting in more injuries and death related to the battle.” The Daily Evening Bulletin of Philadelphia, on November 23, remarked that there was “scarcely a house in Gettysburg where one cannot see half-a-dozen of these dangerous missiles lying on the floor or in the yard…The children play with them, and visitors to the field are offered their choice, for a small sum…We merely make a record…that those who are so careless as to handle shells full of powder will be made more prudent from the warning.”

Russell M. Briggs remarkably lived until September 8, 1885. The 1880 Federal Census returns for Philadelphia, on June 4, 1880, lists his residence as being on “Master Street, North Side,” a widower, retired moulder, whose disability was the “loss of both arms.” He is buried in Mt. Moriah Cemetery of Philadelphia, along with other family members.

Interestingly, just a few years ago in 2011, 148 bullets were found on Culp’s Hill at Gettysburg, inside one of what are called the ‘witness trees,’ by the national park’s workers. Regrettably, ‘unexploded ordnance’ such as mines, are still resulting in casualties within some sixty-three countries world-wide. The late Princess Diana of Wales, as is well-known, made it a goal of her life, to eradicate such ordnance in places such as Angola in defense of the children residing in such places, which at times continue to explode, bringing about loss of life.

Regrettably, as long as there is war, there will always be casualties after any given conflict, that may affect generations to come.