In the years that followed, the Society continued to improve the building to accommodate its collection. But there was another growing concern—the threat of fire. The original fireproof storage area was not large enough to store the Society’s entire collection, and members worried that a fire could destroy or damage its irreplaceable documents, as they had witnessed in other cities during the Civil War and the Chicago Fire of 1871. So in 1902, the Society decided to embark on an ambitious building project to provide more space for its books, manuscripts, and portraits and ensure that these treasures would be adequately protected.

The Society appealed to its membership to raise funds. In an appeal letter, the Society stated: “The Historical Society of Pennsylvania is about to take a very important step. Its invaluable and constantly growing collection of books, manuscripts, portraits, etc., in many lines unequalled by that of any other institution in the world, imperatively demands enlarged accommodations. . . . The new work and the old, extended and improved, must be of the best modern construction and absolutely fireproof, since much of the material intrusted to the care of the Society is of priceless value, and, once destroyed, its loss would be irreparable.”

Above: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania with the Jordon Annex, Society Photo Collection

The administration of Samuel W. Pennypacker requested assistance from the state legislature, which appropriated $50,000 toward the building project. This was not enough money to complete the construction of an entire new building, but it was enough to fireproof the main hall. Architect Addison Hutton drew up plans for the construction of the modified structure on the west side of the mansion—a spacious hall for Society meetings.

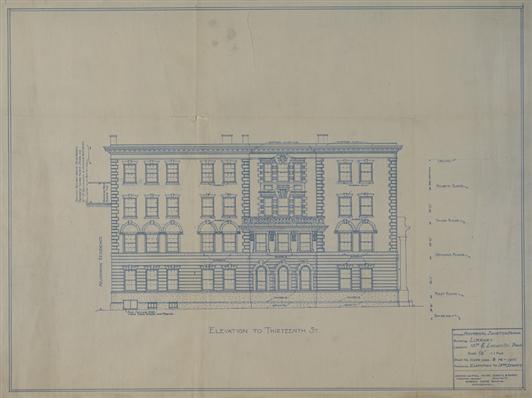

Above: Architectural elevation of HSP from 13th Street, Institutional Archives

These plans were approved by the Society in 1904, and the official “ground-breaking” was held on May 24. During construction, the Society took pains to make sure the building was as fireproof as possible. Its thick walls were made of brick. No wood was used in the construction, not even for the bookcases or furniture. Each room was divided by a fireproof door hung on an inclined railway track, counter-weighted so that when the temperature rises a fusible plug melts and the door automatically closes. On April 24, 1905, John Frederick Lewis, chairman of the Society’s Building Committee, reported that “the inspector, after having examined the building from the roofing to the cellar, said that it was the most perfect fire-proof building of which he had any knowledge in this portion of the country.”

For the second phase of construction, the Society secured an additional $100,000 from the state legislature in 1905. This undertaking replaced the Patterson mansion with a red brick structure that was fireproof and better complemented the new construction. The demolition of the classically built mansion and replacement with the plain bricked structure was highly criticized during a period when Neo-Classical and Gothic architecture were at their height. One article lambasted that “(the building) is cheap and vulgar, weak, cold, ugly, is obvious to all who have seen it; that it has no charm, no character, no dignity, no interest.”

Above: 1910 Opening Gala, Institutional Archives

In April of 1910, after construction was complete and the museum and library collections were in place, the building opened to the public with much fanfare and two days of celebration. On April 7, guests were invited to explore the new building and examine the Society’s rare books, manuscripts, and paintings. That evening, a distinguished group of historians, scholars, Society members, and esteemed guests gathered in the Society’s Assembly Hall for a formal banquet. Guests filled the long tables and feasted on little neck clams, planked shad, and fancy cakes. They smoked cigars and sipped cognac. Silk flags and banners hung from the balcony above, and the hall was adorned with flowers, plants, and palms.