This Wednesday, April 15, HSP will host a discussion about the life and legacy of Richardson Dilworth with journalist Peter Binzeno and Deborah Dilworth Bishop, Dilworth's daughter.

A politician and liberal reformer, Richardson Dilworth served as mayor of Philadelphia from 1956-1962. His vision for the city shaped much of what we recognize about Philadelphia today: Independence Mall, Society Hill, SEPTA, and the public park system. With the support of political ally and personal friend Joseph Clark, he denounced municipal corruption, supported civil rights, fought segregation in private schools, rallied for public housing, and restored much of the city’s history as part of an urban renewal program that would bring the City of Brotherly Love back to life.

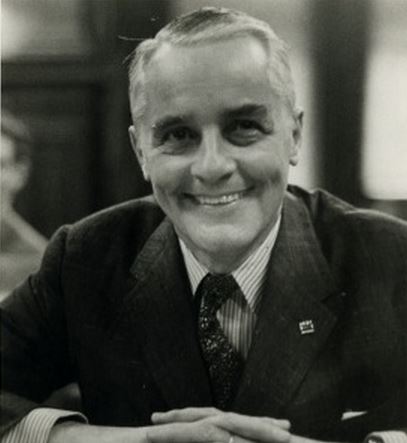

An undated photograph of Dilworth

Richardson Dilworth was born in Pittsburgh on August 29, 1898. During WWI, he served in the Marine Corps and was awarded a Purple Heart for wounds suffered in combat. Dilworth graduated from Yale University in 1921 and earned a law degree from the same institution five years later.

After graduating from law school, Dilworth began working with the firm Evans Bayard and Frick (now Pepper Hamilton LLP) and represented several large companies including the Philadelphia Transit Company, the Triangle Corporation, Curtis Publishing, and Time, Inc. At the same time, Dilworth became involved in municipal reform politics as a Democrat, in an attempt to change six decades of Republican leadership in City Hall. Then, at the start of World War II, Dilworth re-enlisted in the Marine Corps at age 43 to serve in Guadalcanal, a service for which he was awarded a Silver Star for bravery in combat.

Richardson Dilworth’s career as a politician was not immediately successful. He lost his first election in the 1947 race for mayor of Philadelphia to Republican incumbent Mayor Bernard Samuels. Philadelphia had been led by Republican mayors for more than six decades and many did not support Dilworth’s campaign platform, which criticized municipal corruption in an effort to strengthen the local government’s role in city planning.

Finally, political success came two years later when Dilworth was elected city treasurer, Clark was elected city controller, and Democrats won fifteen of the seventeen council seats. As city treasurer, he contributed to the draft of a new city charter that consolidated government offices and made official examinations mandatory for civil service employees. The next year, Dilworth ran for governor of Pennsylvania, but lost a close race to John Fine.

In 1951, at the same time that Dilworth was elected district attorney, Clark was elected the first Democratic mayor of Philadelphia in 67 years. In 1955, Dilworth was elected mayor as Clark went to the U.S. Senate. Together, their administrations launched one of the largest urban renewal programs in the nation and ushered in an era and tradition of political reform in Philadelphia.

Richardson Dilworth campaigning in front of the Bellevue Hotel on the day before the 1951 election.

During the 1950s, Dilworth and Clark worked together to reorganize and rejuvenate the city in what was tagged “Philadelphia’s Modern Golden Age.” Under their administrations, the city’s parks and historic sites were restored, the public transit system was reformed, a public housing system was established, and economic development was encouraged along the waterfront. Dilworth outlined the Philadelphia of today: Independence Mall, SEPTA, Society Hill, community centers, and public parks. The city also became the first in the nation to fluoridate its water, which at the time was thought to be a Communist plot. As mayor, he served as president of the American Municipal Association and of the U.S. Conference of Mayors as well as a member of the Governor’s Commission on Constitutional Revision. Throughout his career, Dilworth fought against segregation in private schools and supported organized labor unions as well as civil rights.

In 1962, Dilworth resigned the office of mayor in order to run for governor again, a race that he lost to William W. Scranton. Three years later he was appointed president of the Philadelphia Board of Education, where he served until his resignation in 1971.

Dilworth died on January 23, 1974, in Philadelphia.

More than fifty years after his mayoral election and almost four decades after his death, Richardson Dilworth is remembered as the Philadelphia mayor who fought for the city he loved. His legacy lives all over the city, from tourists at Independence Hall to commuters on the Market-Frankford line, from historic preservation in Society Hill to public housing communities, from city playgrounds to City Hall.