As the digital collections intern at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, I have been working on digitizing and creating metadata for the Pennsylvania-German collection (V80). The collection consists mostly of Geburts- und Taufscheine (birth- and baptismal certificates), furthermore there are some confirmation certificates, writing exercises, house blessings, bookplates, one butcher’s certificate, an indenture, a watercolor, and some facsimiles of Pennsylvania German fraktur art.

This blog post is about the spelling of names in fraktur, particularly in Geburts- und Taufscheine. While extracting metadata from the birth- and baptismal certificates, it occurred to me that in different documents, some people seemed related yet the spelling of their names were different. However, if you would pronounce their names, they would sound very similar or even the same.

Putting this observation together with a little research on additional information taken from the documents themselves, such as names of parents, names of townships and date-ranges, it became clear that some differently-spelled but similar-sounding names were in fact representing one and the same person or a family-member. In fact, that particular realization greatly helped to clarify that several documents --and respectively the people-- were related to each other.

Last names

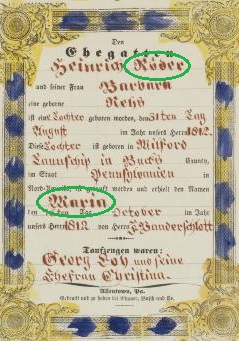

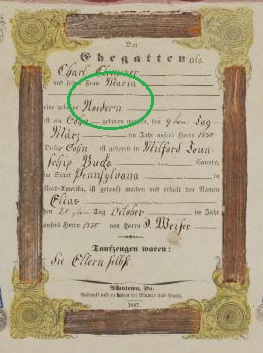

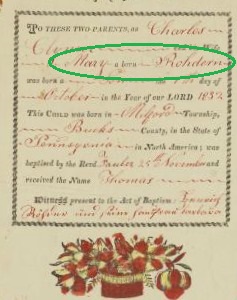

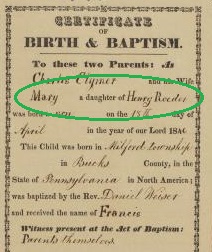

Let me give you examples taken from this collections, where name-spellings appeared in different versions but which in fact turned out to represent one person or immediate family members. The following images show how the name of Maria Röder appears in different spellings including Roeder and Rohder (record no. 12577 & related objects):

The situation is very similar with the occurance of the last names Clemmer and Clymer (who are actually related to the Roeders, record no. 12582 & related objects), and Merckel and Merkel (record no. 12675 & related objects).

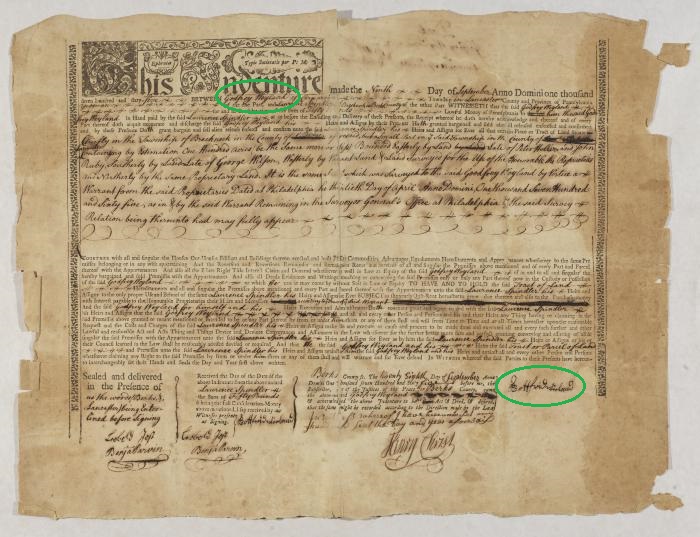

Another example, and the most compelling one about the interchangeability of name-spellings can be found in the Indenture between Godfrey Weyland and Laurence Spindler (record no. 12637).

In this document, two versions of the same name appear within one document (see below). The appearance of the name in the official text is stated as Godfrey Weyland and the signature on the bottom right reads Gottfried Wieland. So while the official document spells his name in the anglicized way, the person still signed his name the German way.

First names

First and last names were not always anglicized together. My examples above pertained mainly to anglicizations or sound-transcriptions of last names. However, the indenture above (Godfrey Weyland - Gottfried Wieland) already shows how the spellings of first names were also subject to change.

Names such as Heinrich may have records describing him as Henry, and Maria could be found as Mary. The example for Mary can be seen in the three images above. Below you can also see the change from Heinrich Röder, father of Maria (record no. 12577) to Henry Roeder, father of Mary (record no. 12592).

In another case the name Feioleta was later transribed into Violetta (record no. 12677). Feioleta is the way a German speaker would literally pronounce the English name Violetta.

Abbreviated names

Furthermore, some first names may appear abbreviated in a way that seems rather unusual today. For example: Mar: Macht: Schulze (record no. 12571) is an abbreviation for Maria Magdalena Schulze, as a later document verifies (record no. 12576). Concluding from the transcription of the first example, it looks like that “gd” may likely have been pronounced as a “cht” by these people.

Suffixes

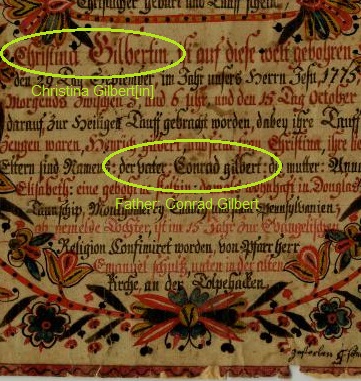

Suffixes can also present a spelling-variation of last names. This applies in particular to last names of women, who may carry the suffix “in,” which in some cases designates the feminine form of a name. Today, this is not done anymore with personal last names, hence it still exists in the designation of professions which distinguish between masculine and feminine form (masc./fem.) such as Lehrer/Lehrerin=teacher, Bäcker/Bäckerin=baker, Professor/Professorin=professor.

In the (V80) collections, the suffix “in” was found several times, and one example is the name “Gilbertin” as documented in the Geburts- und Taufschein Ritschert Rickert (Ritschert=Richard), where the woman’s last name, Gilbert, contains the suffix “in,” (record no. 12563), while her birth certificate clearly indicates that the family name, as represented by the father, was Gilbert (record no. 12604).

In some cases, the suffix "in" can be abbreviated with an apostroph preceding the "n" (see second image of the blog above: Roeder'n). In other cases, the suffix of a simple "n" to a personal last name will indicate being part of that family.

Summary

When doing genealogical research involving German immigrants’ documents such as birth certificates, looking beyond the written text and including the sound of the words may reveal otherwise overlooked relationships.

In case of doubt, reading words out loud and imagining what the German pronunciation may have sounded like (experts may additionally take regional variations into consideration) and how they then may have been transcribed into English can lead to new insights. Vice versa it may be helpful to think about how various English transcriptions of German names may have looked and sounded like.

Another aspect to keep in mind is that in the 18th century, women's last names often carried the suffix “in”. Last not least, the anglicization of first names is also something to include when looking at fraktur documents with personal information.

Juliette Appold, PhD, MLIS candidate and intern at HSP Digital Services, October 2014