The Balch Ethnic Images in Advertising collection is intriguing if not problematic. It raises questions of definition, the transient nature of advertisements, and the nature of advertising in general. Much like Scarlet O’Hara— seen at right in what is perhaps the classiest Schlitz advertisement known to man— its existence depends on the kindness of strangers. First someone--in this case The Balch Institute for Ethnic Studies--made the conscious decision to artificially create the collection. The Ethnic Images in Advertising collection is artificial in that it is not the culmination of documents from an individual’s or organization’s daily activities but an amalgamation of mostly unconnected objects.

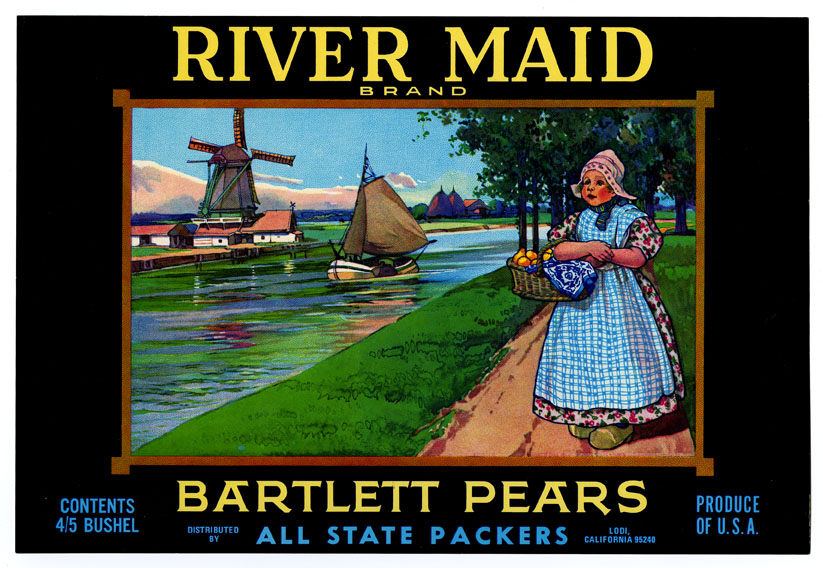

After making that initial decision, they defined the parameters of the collection, mainly in regards to topics and time period. This collection brings together ethnic images from the late 1890s through 1999, encompassing a variety of groups including Arab, Anglo, Latino/Hispanic, Pennsylvania Dutch, Scottish, German, Irish, Italian, Jewish, and Greek. The bulk of the collection however consists of African American, Asian/ Asian American, and American Indian images. There are curious files on “Rural Dwellers,” “Immigrants,” and “Miscellaneous” demonstrating that images were collected but not always assigned to a specific group and unsurprisingly perhaps, that it is not always easy to determine what ethnicity someone is based on appearance alone. Not every advertisement includes such obvious cues as the River Maid crate label seen below. The girl’s bonnet, wooden shoes and the windmill still epitomize “Dutch" to many of us.

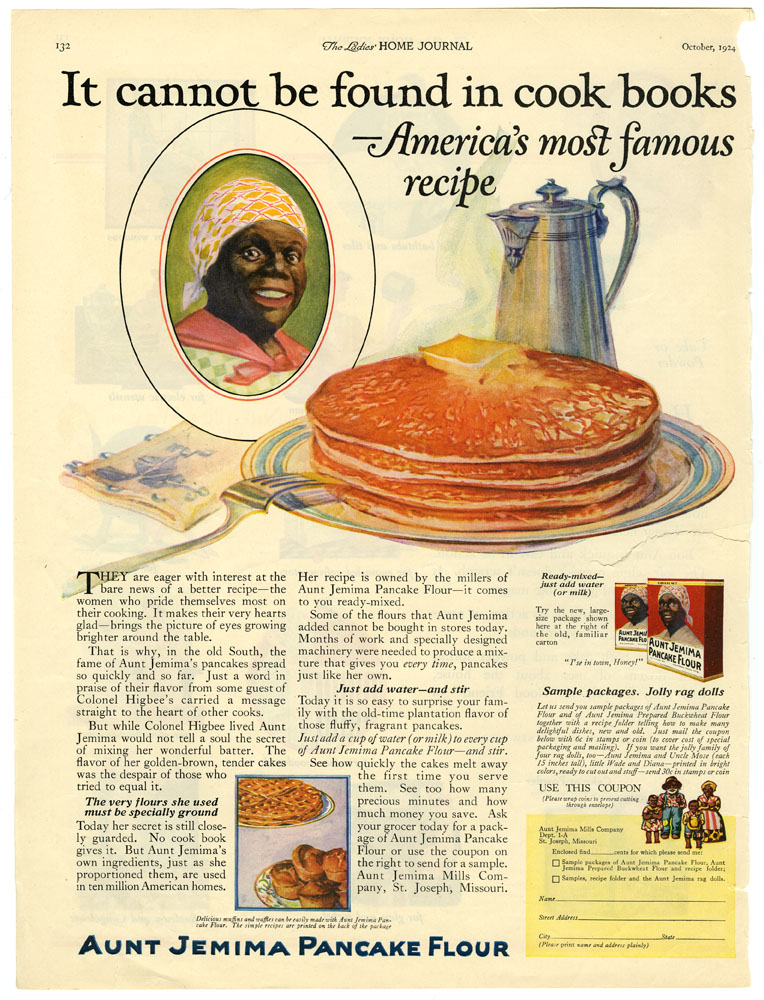

Finding and then preserving a copy of every advertisement conceived and created over approximately one hundred years represents a challenge. It is estimated that by the end of the 19th century Americans could choose from nearly 100,000 magazines. While the sheer volume of print advertisements contributes to the potential survival of content, the ephemeral nature of magazines almost guarantees gaps in the historical record. Unlike family photos or business records magazines were consumable goods, generally meant to be purchased, perused and pitched.  For example, there are approximately ten Aunt Jemima ads in the collection--the highest number for any single product--but even the most cursory internet search uncovers hundreds of different advertisements beginning in the 1890s with Nancy Green, the first woman to portray the fictitious Aunt Jemima all the way through the familiar smiling illustration used today. It is safe to assume that the Balch Institute never intended to collect a copy of each advertisement ever made but rather to select iconic images like Aunt Jemima or Uncle Rastus as well as examples of specific stereotypes such as the Irish police officer, the Italian fruit cart vendor, or the Chinese laundry worker.

For example, there are approximately ten Aunt Jemima ads in the collection--the highest number for any single product--but even the most cursory internet search uncovers hundreds of different advertisements beginning in the 1890s with Nancy Green, the first woman to portray the fictitious Aunt Jemima all the way through the familiar smiling illustration used today. It is safe to assume that the Balch Institute never intended to collect a copy of each advertisement ever made but rather to select iconic images like Aunt Jemima or Uncle Rastus as well as examples of specific stereotypes such as the Irish police officer, the Italian fruit cart vendor, or the Chinese laundry worker.

It would be easy to say that the advertisements are snapshots of American cultural beliefs and the public’s dedication to stereotyping the “other.” Even that poses a challenge, because of course advertisements do not necessarily represent reality, but an advertising agency’s assessment of reality. Historian Roland Marchand makes the persuasive argument that through their work ad men defined the American dream while informing the public on how to attain said dream; they sold the dream along with the products. Though his book, Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity 1920-1940 only deals with a portion of the years represented in the Ethnic Images in Advertising collection, it is important to be aware of intent when looking at the ads. A professional ad agent determined how best to sell goods by exploiting and magnifying consumer desires and fears, even if it meant defining those desires and fears for the consumer first.

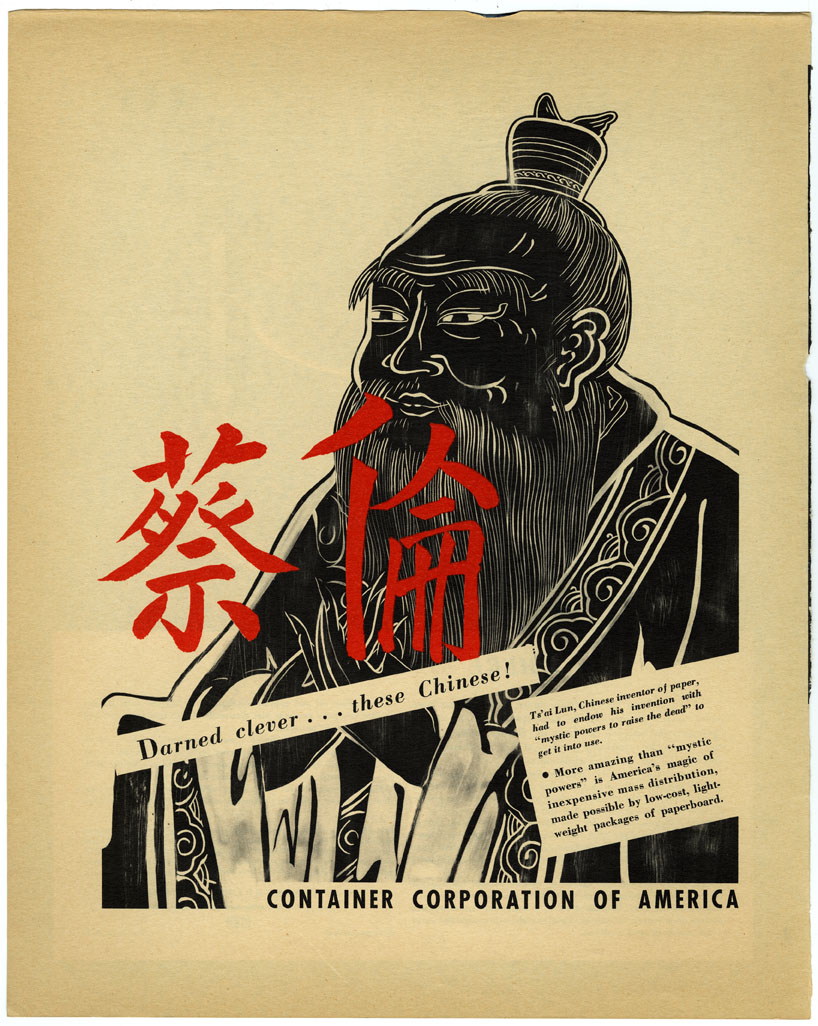

The Balch Ethnic Images in Advertising is problematic for another much more visceral reason. A number of the advertisements rely on negative stereotypes to sell everything from breakfast food and alcohol to interstate travel. It is hard to look at negative images and write descriptions of what is now understood to be racist, derogatory, or at the very least demeaning. Complicating matters are the so-called positive stereotypes such as the scholarly Asian, the happy African American domestic or noble American Indian. Take for example the Container Corporation of America ad seen at left. Here we see Ts’ai Lun (or Cai Lun) a Chinese eunuch during the Han Dynasty who is credited with improving the process of papermaking. Existing stylistically somewhere between a woodblock print and an ink wash, the ad exclaims “Darned clever...these Chinese!” On the surface the ad is complimentary maybe even flattering. Reading on however, we learn Ts’ai Lun had to endow his paper with "'mystic powers to raise the dead' to get it into use,” while America’s magic is "low-cost, light-weight packages of paperboard." According to the ad, improved technology was not sufficient to convince “darned clever” Chinese people to take up Ts’ai Lun’s invention; it was only through superstition that people were convinced. The presumably American viewers of the ad are assured they need no such superstitious contrivances. With a wink ad men tell consumers who is really clever.

The Balch Ethnic Images in Advertising is problematic for another much more visceral reason. A number of the advertisements rely on negative stereotypes to sell everything from breakfast food and alcohol to interstate travel. It is hard to look at negative images and write descriptions of what is now understood to be racist, derogatory, or at the very least demeaning. Complicating matters are the so-called positive stereotypes such as the scholarly Asian, the happy African American domestic or noble American Indian. Take for example the Container Corporation of America ad seen at left. Here we see Ts’ai Lun (or Cai Lun) a Chinese eunuch during the Han Dynasty who is credited with improving the process of papermaking. Existing stylistically somewhere between a woodblock print and an ink wash, the ad exclaims “Darned clever...these Chinese!” On the surface the ad is complimentary maybe even flattering. Reading on however, we learn Ts’ai Lun had to endow his paper with "'mystic powers to raise the dead' to get it into use,” while America’s magic is "low-cost, light-weight packages of paperboard." According to the ad, improved technology was not sufficient to convince “darned clever” Chinese people to take up Ts’ai Lun’s invention; it was only through superstition that people were convinced. The presumably American viewers of the ad are assured they need no such superstitious contrivances. With a wink ad men tell consumers who is really clever.

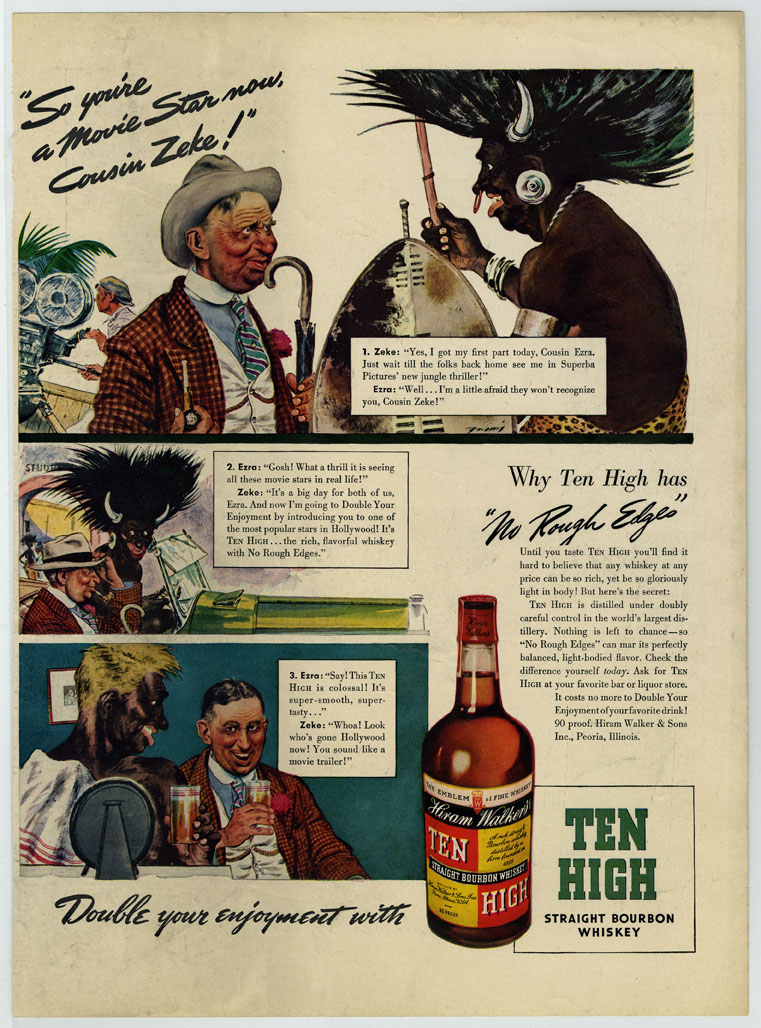

One image for Hiram Walker High Ten Whiskey was a source of much consternation for this author. Formatted to resemble a comic strip, the first image shows a white man Ezra, talking to a wild-haired African man Zeke, who wears an animal print loincloth, horns and a ring through his nose. We come to learn that the men are cousins and that Zeke has recently landed a role in his first Hollywood film. In the last panel Zeke has removed the wild hair, horns and nose ring and is in the process of removing the dark make-up from his face revealing a white complexion and a shock of blonde hair. Clearly intended to elicit a laugh, the punchline now struggles under the heavy weight of over 150 years of blackface and the stereotypical image of Africans--if not African Americans--as savage and frightening.

One image for Hiram Walker High Ten Whiskey was a source of much consternation for this author. Formatted to resemble a comic strip, the first image shows a white man Ezra, talking to a wild-haired African man Zeke, who wears an animal print loincloth, horns and a ring through his nose. We come to learn that the men are cousins and that Zeke has recently landed a role in his first Hollywood film. In the last panel Zeke has removed the wild hair, horns and nose ring and is in the process of removing the dark make-up from his face revealing a white complexion and a shock of blonde hair. Clearly intended to elicit a laugh, the punchline now struggles under the heavy weight of over 150 years of blackface and the stereotypical image of Africans--if not African Americans--as savage and frightening.

Still, the Balch Ethnic Images in Advertising is intriguing survey of American advertisements in a variety of formats. There are a number of labels, primarily from crates and boxes, but also from canned fruits and vegetables. Maps, menus, placemats and even a few playbills help to round out the collection. The third box of the collection which constitutes additions taken in 2005 included two hand fans picturing African American children and women in various intellectual pursuits. Some of the imagery may prove an intellectual or ethical challenges, but they are worth undertaking as they help reveal a more nuanced understanding of American advertising.

Check out the link to the full collection below and tell us what you think.