The following article was written by HSP volunteer Randi Kamine and is being posted on her behalf.

"My Dearest X.Y.Z. I want to tell you everything that has occurred lately and I want you to ask me questions which I am bound to answer.” So begins the first entry in the diary written by Selina Richards Schroeder in early 1889."

This diary is the first of three extant diaries in the possession of HSP in the Schroeder family papers (Collection 4054), which was recently processed. The second volume continues to May 1889; Selina was to turn fourteen later that year. The last of the three diaries ends in the year 1891 when Selina was sixteen.

Selina was the daughter of Louisa and Gilliat Schroeder. Gilliat uprooted from Mobile, Alabama, to New York where he developed a thriving business in the commerce of cotton. The family was upper middle class. Their home base was New York City. Selina, in her musings, did not aim to place herself in the context of social or economic class. However, class distinction is apparent in Selina’s excellent handwriting and grammar and the activities in which she participated, including painting lessons, music lessons, drawing lessons, and buying hats and dresses in up-scale shops in New York. She belonged to the economic class whose members were literate and had time and means to reflect, to the extent there is reflection in her writings.

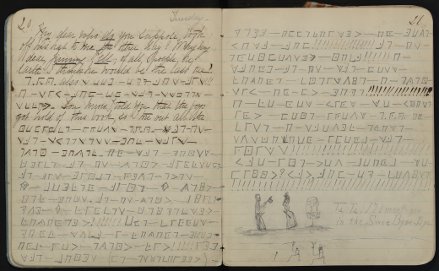

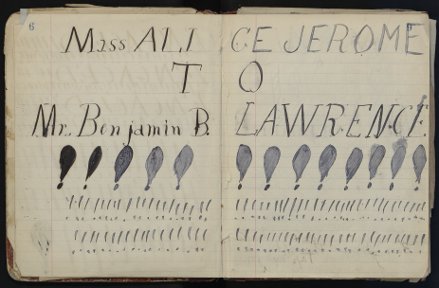

The diaries give the reader an insight into the late 19th century adolescent world. Particularly, reading Selina’s entries casts some light on the function diaries had for Selina and girls of that era. She writes about friends, family, and herself in often candid prose, although friends and family are seldom introduced by name, which makes it difficult to figure out who is who (she uses initials and nicknames more often than full names). While much of the correspondence in the Schroeder family papers from which the diaries emerged is formal and stilted, the diary of the young girl is open and intimate. She was adamant, however, that her thoughts stay private between her and her written words. To provide secrecy she often wrote in code. [See example below – can you figure out the code?]

Selina writes about things teens today are concerned with (albeit in hand written form as opposed to digital). Indeed, one may observe that things have not changed much when it comes to the thoughts of teenage girls. There is little in the way of comments on current events and few political observations.

The last of the three diaries is filled with ephemera collected from dinners, concerts, and events Selina attended. In the three year period Selina wrote these diaries, she began to take her place in the society in which she is surrounded. It is perhaps in the third volume that readers can best capture the tone of upper middle class urban culture.

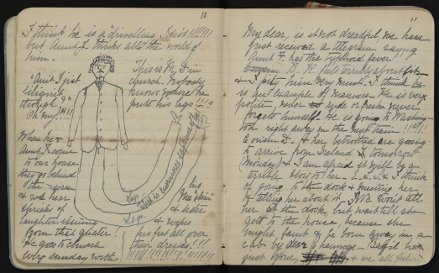

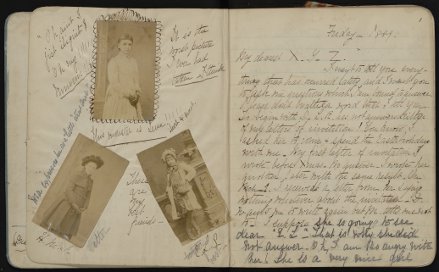

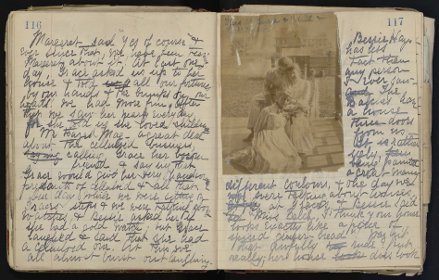

In the first volume there is a stern warning that, should the book be found, it should not be opened. Selina writes, “This book is absolutely private – except to S.R. S.[Selina herself] and her two friends E.L.S and X.Y.Z.” (Perhaps using a convention used by diarists in the nineteenth century of writing to an imaginary friend in the second person). She writes that she wants “to tell you everything that occurred lately.” This first page of the first volume has a photo of Selina and two of her friends [see photo below]. It seems that despite her warnings her secrets were not well guarded. She writes shortly after starting the diary that “Harry, and Jim and G. got hold of this book and read part of it. I was so mortified that I tore part of it up and put in the fire !!!” She will henceforth “carry the keys to my desk in my corset so nobody can get them.”

Selina’s cares revolve around who “stands up” for her and whose friendship disappoints her. In the first few pages, she gives written portraits of several of her friends. As she herself acknowledges, most of her comments are negative. She tries hard to be generous, but her compliments tend to be left handed and she quickly veers toward criticism even when starting out with a positive observation about the character, looks, or demeanor of her friends. She refers to her brothers as “the brats” throughout the diary.

Young men were at the top of Salina’s thoughts. Her descriptions of the boys in her dancing class tend to be caustic and not terribly kind. For example, “He looks as if he had swallowed a bayonet – so stiff.” Indeed, descriptions of boys, news of engagements, observations of male-female relationships predominate throughout this first volume. She wonders which of the women a boy named Basil has been pursuing for marriage—will she be the the one he loves or the one who has money? She appreciates praise given to her by her father. “Papa says I said two very clever things at dinner tonight” she writes. After a joke about grass and hay fever, (“I think that was very clever of me.”) her Aunt M. and Pa were talking about how “much darker and more Indian like” the Americans were getting , Selina quipped, “perhaps in another generation we would all be perfectly black – I think that was rather clever too, don’t you?”

There were, however, moments of serious news. “My Dear [speaking to her diary], is it not dreadful, we have just received a telegram saying Aunt F. has the Typhoid fever.” Family planned to be going to her side, in Washington, the day after hearing the news.

Comments on current events are few and far between. However, Selina does report that she was present at the New York City celebration of the 100th anniversary of George Washington’s inauguration on April 29 through May 1, 1889. She saw President Benjamin Harrison “as he went by on his boat as all the men-of-war saluted him. He was rather late and we thought perhaps that Baby McKee [Harrison’s grandson] had left his bottle behind and had to go back for it….” Later she saw the President drive by City Hall. “He stayed so long at his lunch we were afraid he had had an attack of indigestion because he had eaten so much.” Always the wisecracker.

Near the last pages of volume one, Selina has this to say about “Society.

"My Dear, there was such a delightful young beardless youth, Oh so handsome at The Wick’s. His name was Douglas Taylor. He was awfully jolly and clever. He was not a bit of a flirt and he and I looked out the window and had lots of fun. But he does not appear in Society like those ossified “beardless” idiots who do. I’m not going to let my children (particularly boys) make their appearance until they are twenty-five, as I think these youths or “cads” who go out in Society put on airs and are unbearable and detestable…. [T]hese youthful, idiots, beardless cads monopolize Society."

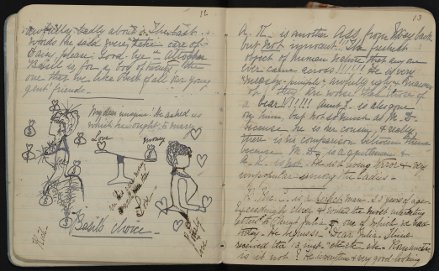

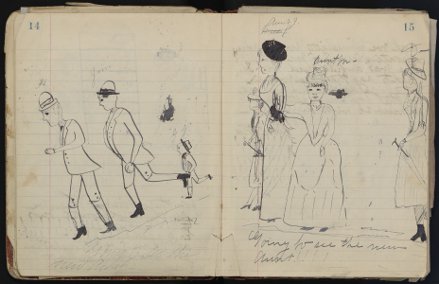

The second volume continues in 1889. “It is absolutely necessary no one shall open it [the diary] but myself and my chum Edith L. Speyers,” she writes. After writing, “I never get tired of writing in it and it affords me unlimited pleasure and fun,” the next twenty pages are taken up with the topics of love and romance. “Engaged: Miss Alice Jerone to Mr. Benjamin B. Lawrence (Uncle Ben) [she writes in large capital letters taking up two pages]. The most exciting thing that has happened in years !!!!!!!” This volume is replete with drawings depicting couples, women swooning over men, men swooning over women, and couples in various social activities such as rowing along a river. A drawing of said Uncle Ben and Miss Alice has the caption, “This is Aunt Alice and Uncle Ben out walking. He is so much in love with her that he can’t keep his eyes off her…This is so romantic.” Selina does not seem particularly aware of a larger meaning of events or of time passing in any historical sense. Selina’s identity as an urban, elite young woman is not explored very deeply in her day-to-day observations. She easily accepts the social order as natural.

Despite Selina’s desire for strict secrecy concerning her own diary, she was apparently not too shy about delving into others’ confidential papers. She writes, “We have just discovered a whole package of letters from Berkely MacCauly’s ten page letters !!!!” to her Aunt Julia. “Strictly private,” Selina warns above this confession, “Only S.R.S. and E.L.S. can see this.” Apparently, Selina and her friend were well aware they would get into trouble for snooping.

A description and accompanying drawing of the Schroeder family starting on a European trip, (“they are all going to Rome to study art!!!!!”) is indicative of the Schroeder family’s social and economic standing. Unfortunately, although it appears that Selina was among those going, there are no notes about the trip. (Not every page is dated so it’s difficult to say how much time passed between entries.) In this volume there are walks along Fifth Avenue, an East Hampton summer and other idle pastimes that speak to a life of leisure and at least moderate luxury. A trip to the dentist also attests to her economic standing. There are visits from friends from England who came bearing gifts and who returned from their European sojourn with seven pairs of gloves.

As in the first volume, not every entry is frivolous. Selina mentions a funeral of a friend’s mother. “Poor Mr. J. Van S … lost his mother a few weeks ago, and is in great danger of losing a good deal of his money.” Not exactly a sympathetic observation, but she does mention that the girl interested in poor Mr. Van S. went to the funeral and wept a great deal, went to bed and was “dissolved in tears almost the entire night.” A few pages later Selina shows a modicum of generosity when she notes that she participated in a fair for the Fresh Air Fund and helped raise $75.00.

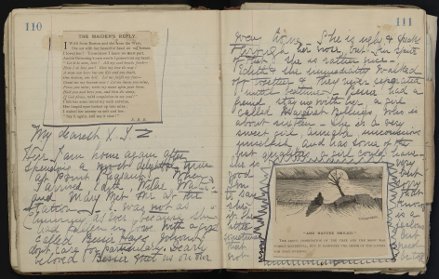

There is one political reference. Selina pasted a printed copy of a poem:

"Why doth the little busy bee

And Blaine and Burchard too

Forever sing the G.O.P

It is their nature to."

The poem above is in reference to James G. Blaine and Rev. Dr. James Burchard. Rev. Burchard was a prominent Presbyterian New York minister and supporter of James G. Blaine. Burchard was accused of killing the chances of Blaine winning the Presidency in 1884 against Grover Cleveland by Burchard’s bigoted slurs against Roman Catholics.

There are more printed poems, stories, and vignettes in this second diary than the first. Selina’s drawings have improved and her world seems to have expanded a bit. She took up photography and photographed places she visited and her girlfriends. Her primary interest, however, is still with her social “set” and the romantic interactions that seem to be the center of her universe. (“Edith gave me a punch and shrieked, ‘Is that Archie?’ I turned around and spied a pair of legs and a very long nose swaying down 14th Street. I almost fainted…you see I am so excited I can hardly write!”) [Followed by dozens of exclamation marks.] Her adventures in book two include being locked in a closet for a spell and witnessing a runaway horse with an empty wagon.

The third volume starts on December 3, 1890, and has a somewhat different tone than the previous two. There are dozens of loose pages with appointment dates and descriptions of activities. It seems that Selina is busy every day of the week with social engagements. Among her mementoes is a program from her first dinner party at the Berkeley Lyceum on W. 44th Street in New York; playbills for plays at Madison Square Garden and other theaters; and concert programs. The many comments on these souvenirs include, “Grand,” “Splendid,” “Perfectly Divine,” and “Glorious.” It is clear that Selina embraces the time and place in which she lived. And no wonder—her material life is well taken care of. She records a list of Christmas gifts that would be the envy of any adolescent today. The catalogue of thirty-four gifts includes two clocks, a silver pin, a silk bag, stockings, and cash.

Potential romance is still uppermost in Selina’s mind. In speaking of a Mr. Atcheson, she says, “To tell you the truth I am dead gone on him !!!! He is very good looking and has the loveliest smile and a divine voice, and when he looks at me, such emotion thrills through every vein…He is a vision and a Dream.” Whew.

The several drawings of dresses and costumes in the diary are a portent of Selina’s future (see picture below).

In early July, 1891 Selina closes this third volume with:

"I must close with a fond farewell as I am going to Luzerne tomorrow morning… Farewell. S.R.S."

For those of us who remember those tender teenage years, and especially those of us who wrote in diaries, the intimate musings in these books will surely have us thinking, “the more things change the more they stay the same.” And yet, the reader might wonder, while reading about the familiar emotions that were expressed by Selina -- have things really stayed the same, or, with social media being the predominate mode of communication, is there no longer an outlet for this type of expression. Perhaps in studying these and other diaries historians can contribute to a subject that is being intensely discussed these days, that is, the diminished sense of privacy, and its implications.

Curious of what became of our carefree teenager? In her mid-twenties she opened a dress shop in Manhattan due to a turn in her father’s fortunes! She married Charles Lawrence in Westchester, New York, in 1900.

For more information on her and other working women see What Women can Earn: Occupations of Women and their Compensation, by Frederick A. Stokes (1899)