By Jo Mikula, Haverford College Philly Partners Intern

With the escalation of the Syrian Civil War as well as a number of smaller conflicts, the UN recently reported that the refugee population has spiked to surpass 25 million people. Countries that border conflict zones are struggling to accommodate waves of displaced people, and are calling upon the European Union and the United States to play a more active role in providing aid and accepting refugees. In the midst of this global crisis, we’re taking a look back at American involvement in the mass displacement of Southeast Asians in the wake of the Vietnam War.

On January 30, 1968, the North Vietnamese army launched a series of attacks on the South Vietnamese army, U.S. forces, and their allies that would signal a turning point in the Vietnam War. These attacks, known as the Tet Offensive, spanned multiple days and became one of the bloodiest campaigns in the Vietnam War. Media coverage of the offensive led many Americans to realize that victory in Vietnam was not, as President Lyndon Johnson had promised, imminent. Public support for the already controversial war began to further deteriorate, with many more Americans calling for the withdrawal of US troops.

By March of 1975—a month before the war ended—it had become apparent that the North Vietnamese army would soon seize control of Saigon. While most Americans in Saigon could easily evacuate before the arrival of North Vietnamese troops by simply going to an evacuation point, it was much harder for the South Vietnamese to leave. Some Vietnamese citizens obtained black market U.S. visas in order to leave the country, while others were smuggled out by American friends. By the time the city fell in April, over 100,000 Vietnamese people living in Saigon had fled, either through evacuation missions run by the U.S. army or of their own accord.

The Saigon refugees prefigured a wave of immigration that occurred after the United States left the conflict. People fled the communist government that had taken control of what was once South Vietnam. Cambodian refugees soon joined South Vietnamese refugees when the Cambodian Communist party declared war on the newly united communist Vietnam. The majority of refugees initially went to camps in other Southeast Asian countries like Thailand, Malaysia and the Philippines. From there, many of the refugees were resettled in Europe or North America.

Official documents now in HSP’s collection raise a number of concerns about the relocation process. One memo from the Red Cross questioned the state of the refugee camps in Southeast Asia, while another mentioned “several occasions where parts of families have been put on different planes leaving Guam and ending [sic] up at different camps in the United States.”

American politicians quickly devised legislation to accommodate this wave of refugees. The Vietnam Humanitarian Assistance and Evacuation Act of 1975 promised financial assistance, medical assistance, and social services to Cambodian and Vietnamese refugees seeking asylum. Around eight to ten thousand of these refugees ultimately settled in Pennsylvania alone, making it home to the third largest population of Southeast Asian refugees in the country.

At its core, the Humanitarian Act sought to assimilate refugees into American culture or, as one document put it, to provide the “adjustment and cultural blending necessary to self-sufficiency” in America. Under the Act, most refugees were matched with local sponsors who provided shelter, clothing, and food, as well as “assistance in finding employment and in school enrollment for children and covering ordinary medical costs.” Sponsors who took up this “moral commitment” included individuals, churches, civic organizations, and state and local governments. The Act also provided resources like

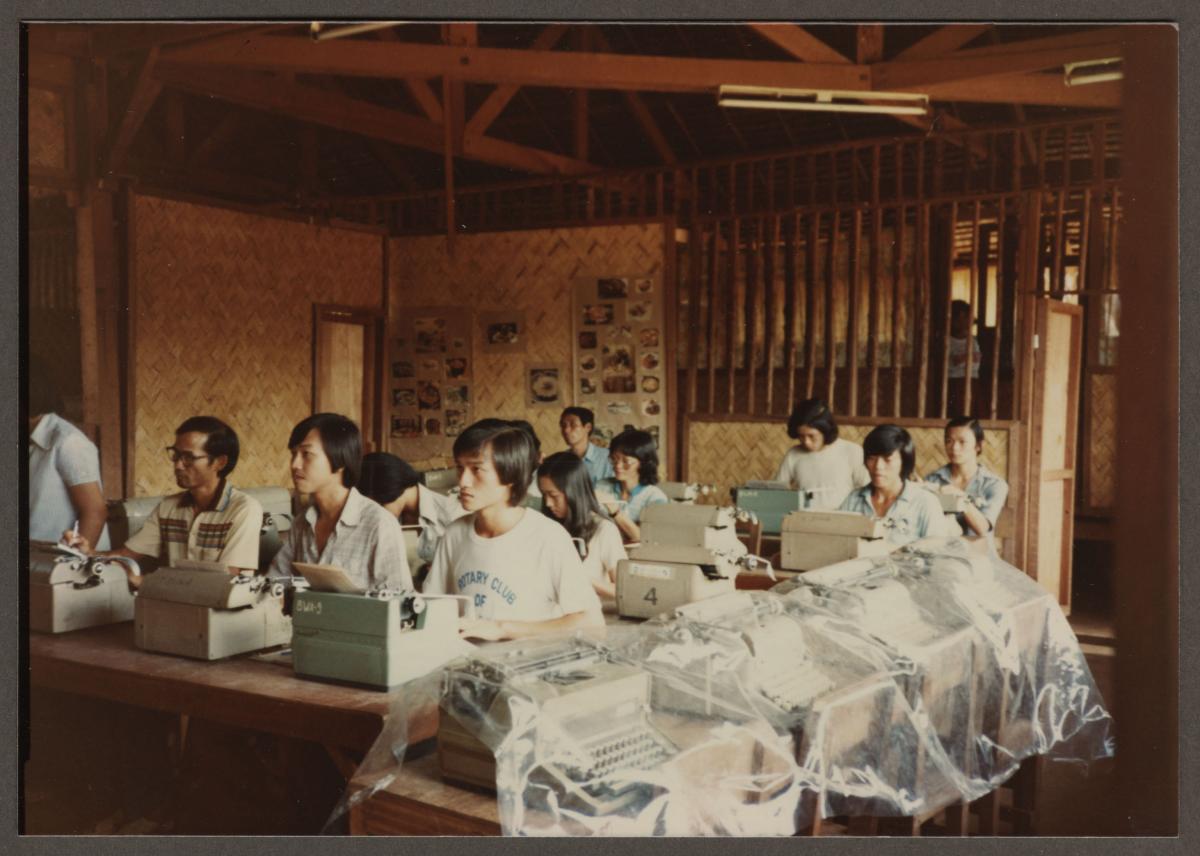

At its core, the Humanitarian Act sought to assimilate refugees into American culture or, as one document put it, to provide the “adjustment and cultural blending necessary to self-sufficiency” in America. Under the Act, most refugees were matched with local sponsors who provided shelter, clothing, and food, as well as “assistance in finding employment and in school enrollment for children and covering ordinary medical costs.” Sponsors who took up this “moral commitment” included individuals, churches, civic organizations, and state and local governments. The Act also provided resources like  language classes and vocational training in an effort to integrate the refugees, along with counseling. A document outlining the Indochinese Refugee Mental Health project states that the counseling for refugees was intended to address the “traumas of emergency evacuation from their homelands and relocation in this (to them) alien culture.”

language classes and vocational training in an effort to integrate the refugees, along with counseling. A document outlining the Indochinese Refugee Mental Health project states that the counseling for refugees was intended to address the “traumas of emergency evacuation from their homelands and relocation in this (to them) alien culture.”

The refugee crisis was often a point of tension between federal and state power. Papers on the counseling programs offered for refugees indicate that “in the areas of mental health and related service, not all states have taken the initiative or found the need to categorically design and/or fund Social Services for the Indochinese refugees.” A memorandum on refugee children meanwhile asserts that a state’s “refusal to accept unaccompanied minors infringes upon federal power to regulate immigration.”

Political disputes surrounding immigration and refugee resettlement continue to this day. California has upheld its sanctuary state policy rather than comply with the Trump administration’s immigration policies. The White House’s decision to cut dramatically refugee admissions has drawn criticism from those who lived through the mass displacements of the 20th century. 50 years on, the 1960s remain as relevant as ever.

References:

History. “Tet Offensive”. Available at: https://www.history.com/topics/vietnam-war/tet-offensive

Lourie, Norman V. Norman V. Lourie Papers. Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Lourie, Norman V. Norman V. Lourie Photographs. Historical Society of Pennsylvania. (From which these photographs of refugee camps in Guam come)

UN Refugee Agency. “Figures at a Glance”. Available at: http://www.unhcr.org/558193896.html