By Kenneth J. Heineman

This article was published in the fall 2018 issue of Pennsylvania Legacies (vol. 18, no 2): Protest in 1960s Pennsylvania.

In popular and scholarly accounts of the American 1960s, student protest looms large—and for good reason. After all, 26,000 US students were arrested for engaging in disruptive demonstrations on or off campus. Such flagship state universities as the University of California–Berkeley and the University of Michigan were well known as centers of often violent student activism and liberal-to-radical protest. The Keystone State experienced far fewer student demonstrations against university military research and the Vietnam War than were seen elsewhere in the country. That is not to say that Pennsylvania’s public and private universities were quiet, however.

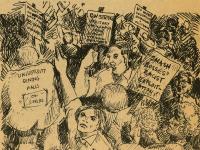

"Rejoice / Liberate yourself / Return your draft card," exhorts this flyer for an anti-war demonstration at Philadelphia's Rittenhouse Square on November 14, 1970. Thelma McDaniel Collection.

Pennsylvania State University, the Keystone State’s flagship institution of higher education, changed dramatically after World War II. Military-related research helped the school grow and provided antiwar students and faculty with a potential protest target. Despite that fact, various factors limited the size and effectiveness of the campus protest movement at Penn State. Moreover, contrary to national trends, Penn State nurtured the growth of a conservative student movement. It is fair to ask—why did Penn State, which represented a proximate cross-section of middle-class Pennsylvanians, diverge from its state and national peers?

Penn State president Eric Walker confidently welcomed the new year of 1968. Both he and the university he led had made a remarkable journey in recent decades. The outbreak of World War II had transformed American universities from cloistered enclaves into instruments of national security. In 1942, the federal government appointed MIT’s Vannevar Bush to lead the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD). Among its many defense initiatives, the OSRD and the US Navy created the Underwater Sound Laboratory at Harvard, at which Walker improved the guidance systems of torpedoes. From sonar to the atomic bomb, American research universities designed the tools of victory against Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan.

Harvard, America’s premiere liberal arts institution, had little interest in continuing applied weapons research after World War II. The nation’s oldest college trained policy makers, not technicians. Penn State’s leadership, on the other hand, recognized an opportunity to build its science programs as the Cold War loomed. Walker, the US Navy, and a team of engineers went to the Happy Valley in 1945. Over the next decade, Walker rose from department head of electrical engineering to dean of the engineering college to vice president for research to, in 1956, president of the university. Walker’s Ordnance Research Laboratory (ORL) thrived, receiving $62 million in defense funding between 1945 and 1965 (nearly $426 million in 2018 dollars). The Navy funded 76 percent of Penn State’s engineering program. The ORL helped develop the Polaris nuclear-tipped missile and boasted a water tunnel with which to test the noise levels of torpedo and submarine propulsion systems. While the Cold War struggle between the United States and the Soviets raged in Korea and Vietnam, Penn State stocked the national arsenal.

American higher education expanded after World War II for a variety of reasons. Generous federal and state funding was a significant factor, as was the “Baby Boom,” which fed more students into colleges. Before World War II, there had not been a single American university with a student population above 15,000. By 1970, the United States had 50 universities that enrolled a minimum of 15,000 students. The postwar “Boomers” were the largest generational cohort in American history. Between 1960 and 1972, 45 million youths turned 18—old enough to go to college or to war. In 1960, America had 3 million college students; by the end of the decade, this number had climbed to 10 million.

While champions of higher education believed that universities were “escalators” promoting the social mobility of low-income Americans, in reality, just 17 percent of college students in the 1960s came from working- and lower-middle-class families. At elite private colleges, the proportion of lower-income students was even smaller. Public universities like Penn State enrolled a somewhat higher number of working-class youths—even so, these schools were often not so much mobility escalators as they were a short leg up to better status. Ivy League alums ruled the universe; state university graduates managed the branch office in Scranton. Thanks in part to the provision of 2-S Selective Service college draft deferments, 80 percent of the soldiers who served in the Vietnam War came from working-class families. Inevitably, they dominated the causality lists. In contrast, one student each from Harvard, Princeton, and Yale died in the Vietnam War. Unwittingly, the federal government nurtured a class divide that literally meant the difference between life and death.

Students, whether morally opposed to the Vietnam War, fearful of flunking out and losing their draft deferments, or both, joined faculty in antiwar protests. By the end of the Sixties, the Vietnam War transformed many campuses into centers of opposition to American Cold War foreign policy. At the same time, campus protest turned millions of working-class Americans against “activist” universities that offended their sense of patriotism and refused them admission—while taking their tax dollars. Public respect for institutions of higher education fell. With that decline came less willingness to fund public universities, especially in states with large working-class populations, such as Michigan, Ohio, and Pennsylvania.

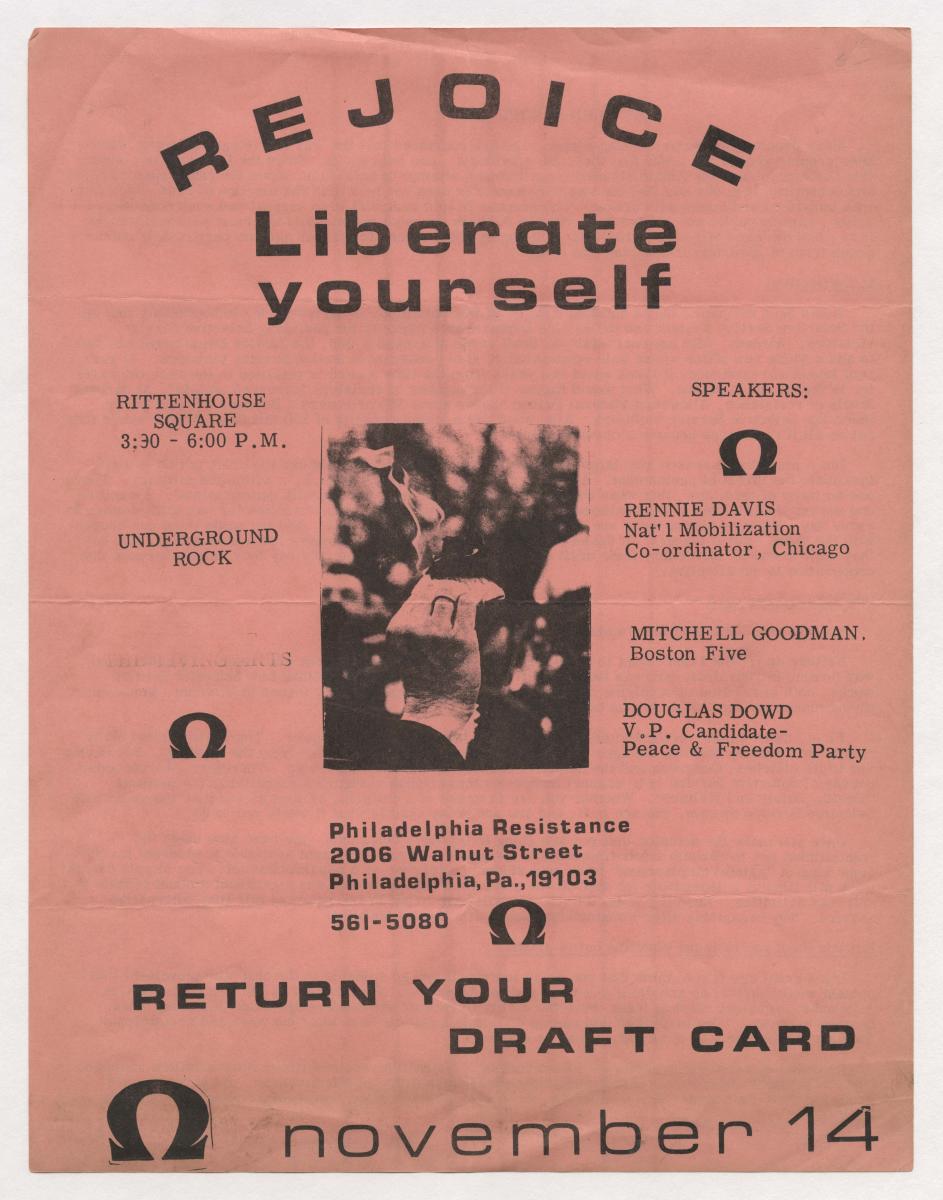

“Support Our G.I.s: Bring Them Home!” Flyer for a Philadelphia march in solidarity with American G.I.s, October 26, 1968. Thelma McDaniel Collection.

From Walker’s perspective, the Cold War and the Baby Boom were the foundations for an academic empire. He expanded main campus facilities to accommodate a student body that grew from 13,000 when he assumed the presidency to 40,000 a decade later. Walker also championed a branch campus system that spread Penn State satellites across Pennsylvania. The number of faculty on the main campus in State College doubled during his presidency, from 1,600 to 3,200, while the operating budget went from $34 million to $165 million ($1.1 billion in 2018 dollars).

After President Johnson escalated the Vietnam War in 1965, student and faculty protest erupted nationwide. Numerous community and campus protest organizations appeared and disappeared. Two student groups proved to have staying power and provided national leadership: the radical Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and the conservative Young Americans for Freedom (YAF). SDS, which grew to 100,000 members before imploding in 1969 over the use of terrorist tactics, claimed a middle-class-to-affluent profile. The student Left in general was overwhelmingly secular, majored in the liberal arts, had expectations of postgraduate employment in the public sector, and came from Democratic households. A third of SDS members had parents who had been leftist activists in the 1930s and were thus nicknamed “Red Diaper Babies.”

Page with illustration of campus protest from Fight Racism! (Boston, circa 1970), a pamphlet published by Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).

On the student Right, YAF grew to 60,000 members. Like SDS, YAF imploded in 1969, split by, on one side, a libertarian faction that opposed America’s Cold War policies and championed the legalization of narcotics and, on the other, anticommunist social conservatives. YAF’s libertarians, like their SDS counterparts, tended to be secular, affluent, and, often, liberal-arts majors. If YAF members belonged to the social conservative faction, they tended to come from lower-middle-class backgrounds, to major in business or the sciences, and to expect postgraduate employment in the military or the private sector. Socially conservative YAF members were often Catholics whose parents had rejected President Franklin Roosevelt’s expansion of government and perceived friendliness toward the Soviet Union. There were few social conservatives enrolled at elite colleges; they generally attended public schools like Penn State.

Antiwar protests, which initially began in 1965 as nonviolent “teach-ins,” or public debates over US foreign policy, gave way by 1967 to confrontations with military and military-related corporate recruiters on campus. Headhunters from Dow Chemical, which manufactured napalm for the Vietnam War, became a magnet for protestors, as did the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC), which provided a visible campus link to the Vietnam War. Liberal arts professors across the nation, but especially at Ivy League schools, demanded the elimination of ROTC programs at their institutions. Such elite universities as Columbia, Harvard, and Yale drove ROTC off campus. In contrast, most state universities, especially those in the South, embraced their ROTC students.

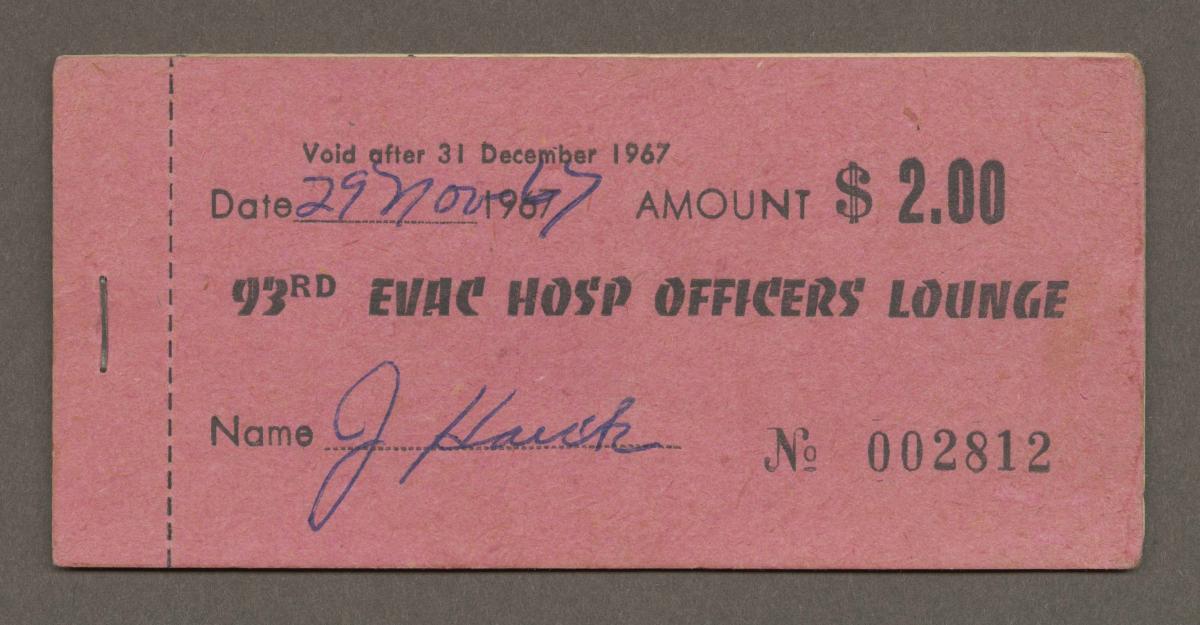

Officers' Lounge ticket, circa 1967, from the papers of Joseph Hauck Jr., who served in Vietnam following his participation in the ROTC program at Georgetown University. Hauck Family Papers.

Along with ROTC, defense-related campus research attracted student and faculty opposition. In 1966, the leftist Ramparts magazine published an exposé on the Michigan State University (MSU) Vietnam Project. From 1955 to 1962, MSU political scientists had helped draft the South Vietnamese constitution and set up its government; its economists had established South Vietnam’s taxation and finance structure; and its police instructors had built a 60,000-strong security force. The school also provided faculty status to 100 covert Central Intelligence Agency operatives working in southeast Asia. The MSU SDS chapter used the Vietnam Project to establish a direct link between universities and the Cold War. It also became antiwar activists’ best recruiting tool.

The University of Pennsylvania’s military-related research also energized antiwar faculty and led 200 students to stage an occupation of president Gaylord Harnwell’s offices in 1967. Penn’s relationship with the US military dated from 1951, and it deepened when the Air Force funded the “Spice Rack Project” and the Army sponsored the “Summit Project.” Both initiatives involved research in bacteriological and chemical warfare. In 1965, the Philadelphia Committee to End the War in Vietnam exposed Spice Rack and Summit. Penn faculty, largely those outside the military-funded sciences, were outraged. Despite its post–World War II expansion of business and science programs, liberal arts faculty and students still defined Penn’s academic culture. Such professors and students were more suspicious of the military and more opposed to US foreign policy than their business and science counterparts. Recognizing campus political realities, Harnwell did not renew the Spice Rack and Summit contracts in 1967, and the university promised to end all such secret warfare research.

Much of the mounting campus unrest in the early and mid-1960s bypassed Penn State. Part of the reason could be found in the university’s geographical isolation from urban population centers. As Penn’s State’s eighth president, Edwin Sparks, had observed, the university was “equally inaccessible from all parts of the state.” University of Pennsylvania campus activists drew upon Philadelphia for financial support and a supply of protestors. Kent State University in Ohio, while located in a small, conservative town, was close to an interstate highway and just 38 miles from Cleveland. The University of Pittsburgh, which made the transition in the Sixties from a small, private college to a large, state-related campus, drew upon a socially conservative local population for its undergraduate enrollment. However, Pitt’s graduate programs, notably in the liberal arts, attracted a national pool of students and faculty who were often antiwar liberals or radicals.

Penn State’s antiwar activists had neither local support nor a much of an oppositional political counterculture. Moreover, Penn State’s undergraduate and graduate students, as well as its faculty, were generally conservative and clustered in the less politically progressive fields of business and the sciences. Liberal arts expanded at Penn State in the Sixties but were not at the heart of the university’s culture.

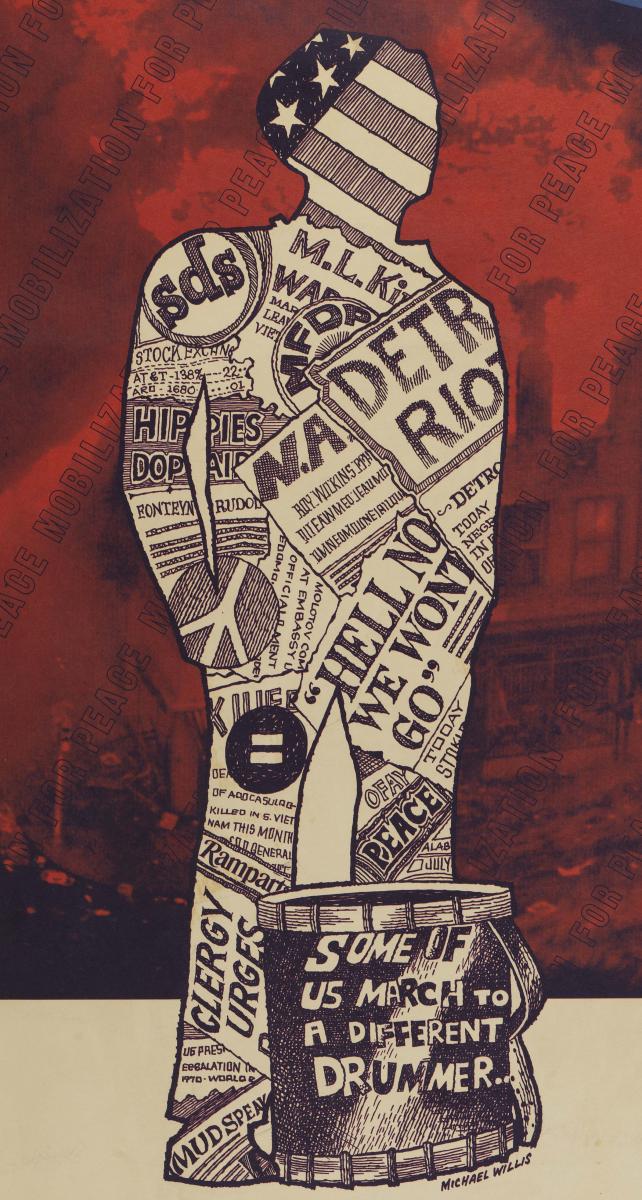

Detail from a 1967 poster by 16-year-old Michael Willis referencing Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), hippies, youth protests, antiwar activism, and civil rights demonstrations. Historical Society of Pennsylvania Miscellaneous Posters Collection.

Despite its limitations as a center of campus political engagement, Penn State produced two student activists of note. The Penn State YAF chapter emerged as one of the largest and most influential in the conservative student movement. Penn State YAF leader Carl Thormeyer could have been the national poster student of the organization’s socially conservative, or “traditionalist,” faction. Thormeyer, who came from a lower-middle-class Catholic background, worked with the small band of student leftists to promote public debate over US foreign policy. Given the apathy of most Penn State students, Thormeyer saw the small campus Left in 1965 as at least willing to argue politely. After graduation, he enlisted in the Navy and served as a meteorologist in the Vietnam theater.

On the Left, Carl Davidson, a philosophy major and son of an Aliquippa mechanic, led a loose confederation of campus radicals. Davidson was a rare working-class campus leftist. He expressed suspicion of upper-middle-class student radicals who advocated violence, regarding them as “elitists” and “fanatics.” Davidson wanted to work with YAF to promote civil debate and mobilize, not antagonize, working-class Americans who were growing angry with a protracted war and an increasingly disruptive antiwar protest movement. In 1966, Davidson became national SDS vice president. His efforts to halt SDS’s drift toward violent confrontation failed, as did Davidson’s hope that fellow radicals would acknowledge the white working-class as a victim of capitalist militarism rather than as an ally of the ruling class.

For Walker, the campus SDS chapter posed little threat. Its ranks remained under 100, and just a dozen students showed up at a February 1968 demonstration. Incredibly, Penn State SDS passed up an opportunity to mobilize students and faculty. It was difficult to miss Penn State’s military research. The name on the building, after all, was Ordnance Research Laboratory. In the spring of 1968, a few Penn State SDSers argued that the ORL represented a prime target. The dominant campus SDS faction, however, focused on supporting the radicals at Columbia who were seizing campus buildings and targeting their university’s military-related research. Expressing solidarity for upper-middle-class students in New York was not going to build a radical movement at Penn State.

There was one seemingly possible threat to Walker’s peace of mind. John Warner, the president of the campus black student organization, the Douglass Association, had led 100 African American students in the takeover of Old Main, the campus administration building. The students rallied for the creation of a black studies program and the admission of more African American students, among several other “non-negotiable demands.” Walker, who had earlier refused to negotiate with the Douglass Association, stated that he would admit more black students. Penn State’s expansion plans had always been committed to increasing enrollment regardless of race.

Walker also did not have to be concerned with the Douglass Association becoming more influential on campus. Warner had expelled whites from an earlier campus civil rights organization, the Student Union for Racial Equality (SURE), and offended many students when he argued that “A white person mourning the death of Martin Luther King. Jr., is like a man on death row mourning the death of the person he killed. He does not mourn because he is sorry; he mourns because he has been found out.”

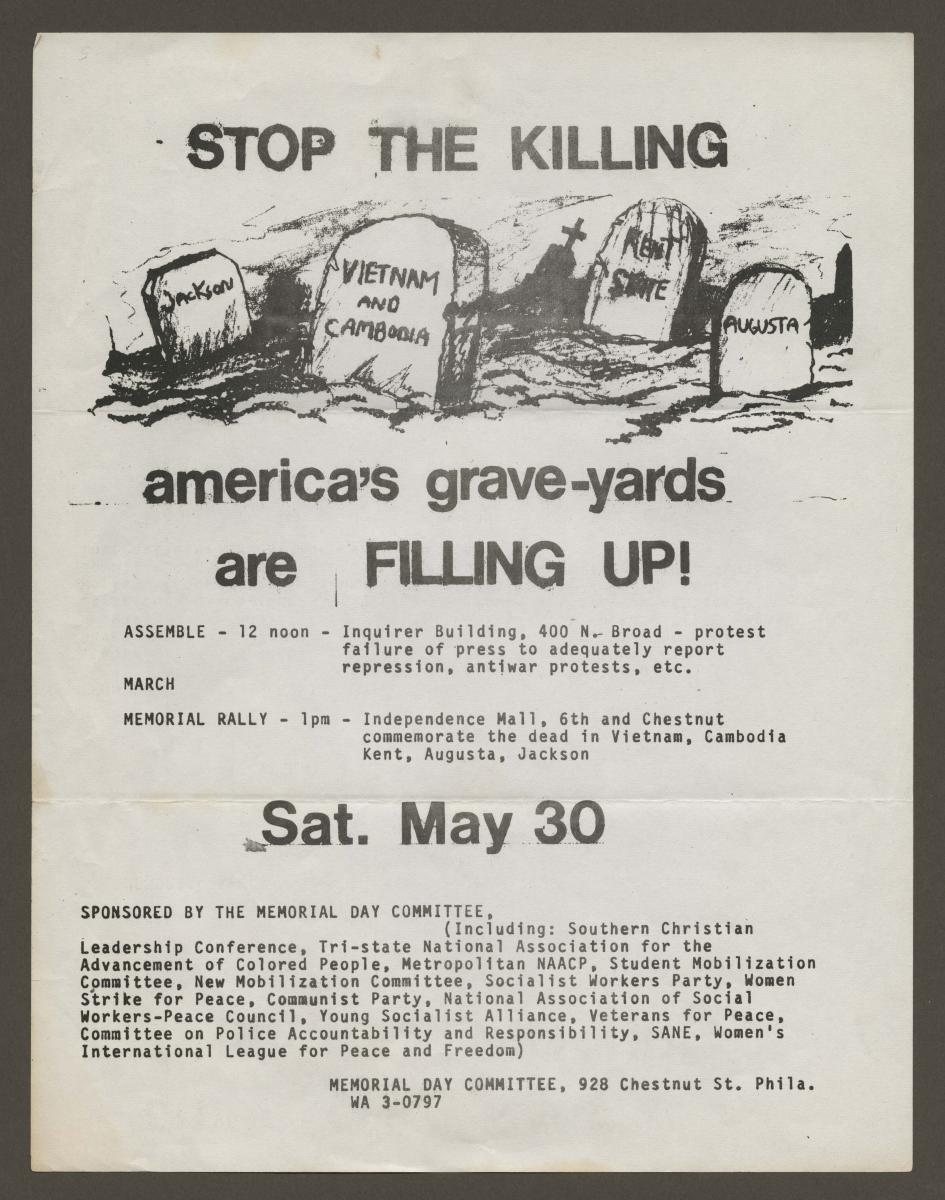

This flyer for an antiwar protest in Philadelphia on May 30, 1970, highlights the recent killings of protestors at Kent State and Jackson State Universities and Augusta, Georgia, as well as those of US soldiers in Vietnam and Cambodia. Thelma McDaniel Collection.

In 1968, Walker had largely dodged “the Columbia Syndrome”—the wholesale student seizure of campus buildings. White and black progressives were divided, marginalized, and outnumbered. It would be two more years before Penn State exploded, and it took the killing of four students at Kent State by the Ohio National Guard to arouse the campus. Although around 2,000 Penn State students demonstrated in protest of Nixon’s apparent escalation of the war by invading Cambodia and the Kent State shootings, protests quickly dissipated, especially once students realized that the invasion of Cambodia would not result in greater draft calls. Unlike his peers elsewhere, Walker could remain confident that while the nation might be tearing itself apart, life would go on in the Happy Valley.

Kenneth J. Heineman is a professor of global security studies at Angelo State University and the author of six books, including Campus Wars: The Peace Movement at American State Universities in the Vietnam Era (New York University Press, 1994), and The Rise of Contemporary Conservatism in the United States (forthcoming from Routledge).

This article was published in the fall 2018 issue of Pennsylvania Legacies (vol. 18, no 2): Protest in 1960s Pennsylvania. Learn more and subscribe.