by Billy G. Smith

This article was published in the spring 2019 issue of Pennsylvania Legacies (vol. 19, no 1): Epidemics and Public Health in Pennsylvania History.

“They are dying on our right hand and on our Left; we have it opposite us, in fact, all around us, great are the number that are called to the grave…To see the hearse go by is now so common that we hardly take notice of it;…we live in the midst of death.” While Isaac Heston penned these words to his brother on September 19, 1793, yellow fever claimed the lives of about 70 Philadelphians each day. “When I see the Metropolis of the United States depopulated,” the 22-year-old moaned, “it is too distressing and affecting a scene for a person young in Life to bear.” A mosquito carrying the virus bit Heston about the time he wrote the letter; he died 10 days later.

It all started in late July 1793 in a brothel near a pier in the northern part of the city. Two mariners, mostly likely from the ship Hankey or one of the other vessels that had arrived a few days earlier from the West Indies, had rented a room at the “disorderly house.” A violent fever quickly killed one of the sailors. An English boarder in the house shivered with an elevated temperature, vomited a black substance, and died a few days later. Mrs. Parkinson, an Irish lodger (or prostitute), suffered with sunken eyes, jaundiced skin, and blood trickling from her nose and mouth for a week before she expired. Both brothel owners died, as did the second mariner and several next-door neighbors.

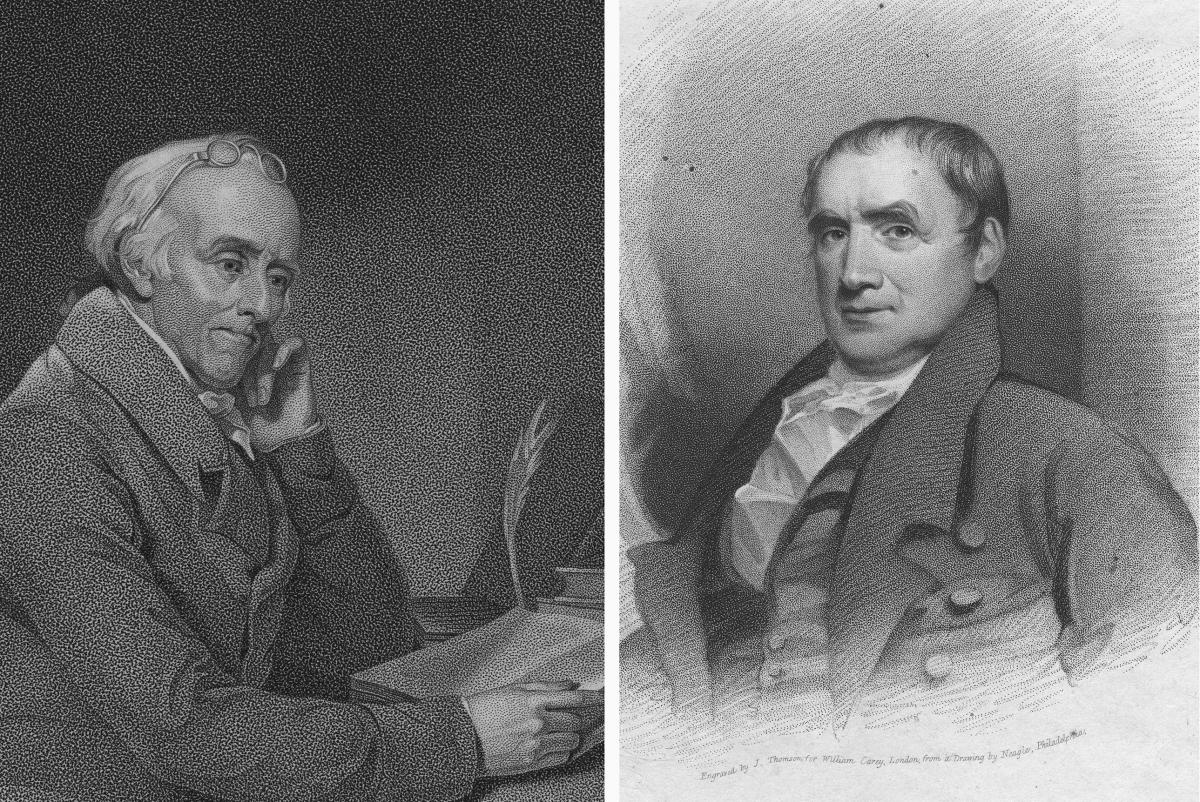

All these fatalities in such a brief time attracted the attention of Dr. Benjamin Rush, the most distinguished physician in the new nation. After visiting a few of the sick people in the neighborhood, he announced in late August that yellow fever now stalked the city’s streets. During the next three months, the disease killed more than 5,000 people—one out of every 10 Philadelphia residents. Not until the late 19th century did physicians understand that infected Aedes aegypti mosquitoes were the source of all this human misery.

(Left) Portrait of Dr. Benjamin Rush; (Right) Portrait of Mathew Carey. Historical Society of Pennsylvania Portrait Collection.

Philadelphians fled in panic. “So great was the general terror,” the newspaper printer Mathew Carey noted, “that for some weeks, carts, wagons, coaches, and [riding] chairs, were almost constantly transporting families and furniture to the country in every direction.” At least a third of the city’s inhabitants abandoned their homes. George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and virtually every other prominent federal leader numbered among the refugees from Philadelphia, the nation’s capital during the 1790s. State and city officials likewise joined the flight. Government at all levels ceased to function. By mid-September, Mayor Matthew Clarkson was the sole elected city administrator who stayed in the city.

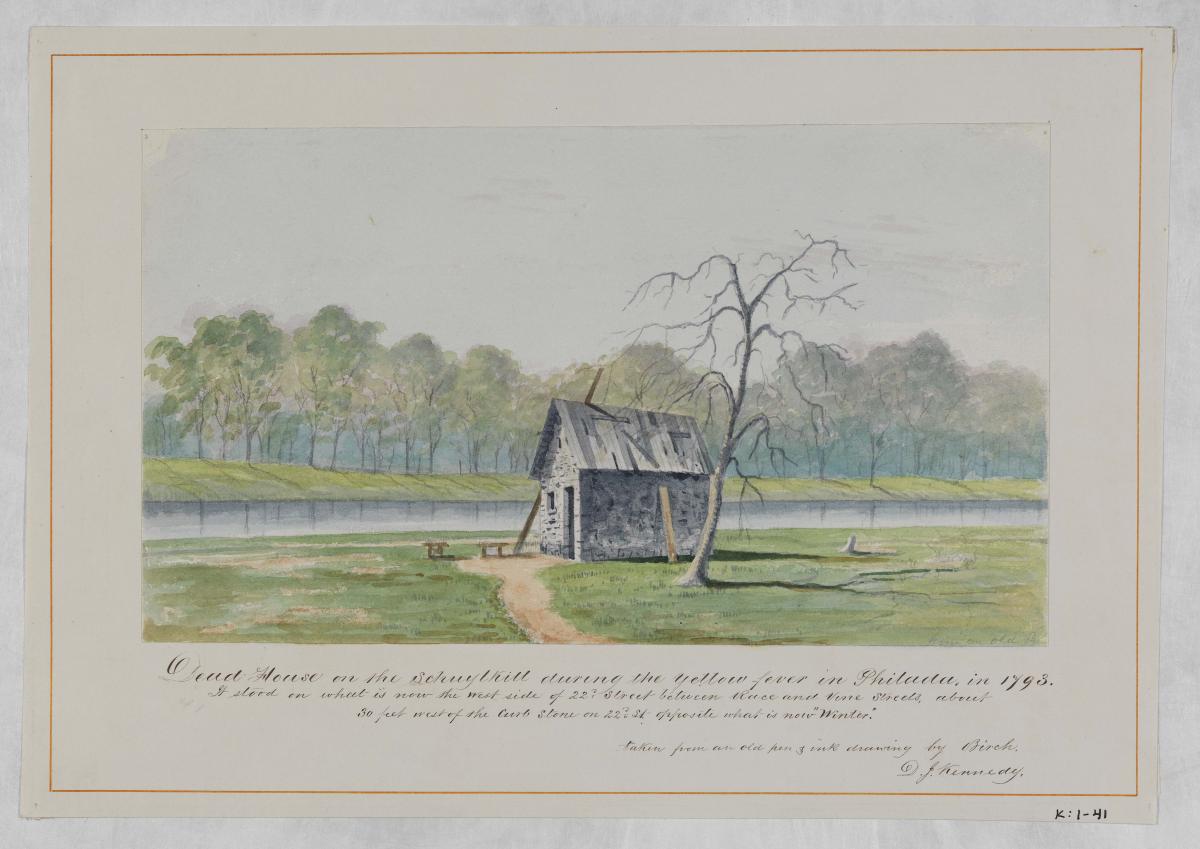

Dead House on the Schuylkill during the Yellow Fever in Philadelphia in 1793, watercolor by David J. Kennedy. David J. Kennedy Watercolors Collection.

In desperation, Clarkson appealed directly to the ordinary citizens of Philadelphia to help. The most pressing needs were nurses to care for the sick, cartmen to carry away bodies piling up in the streets, and gravediggers to bury them. But everybody thought these duties were too dangerous, since they brought one into direct contact with the supposed sources of infection.

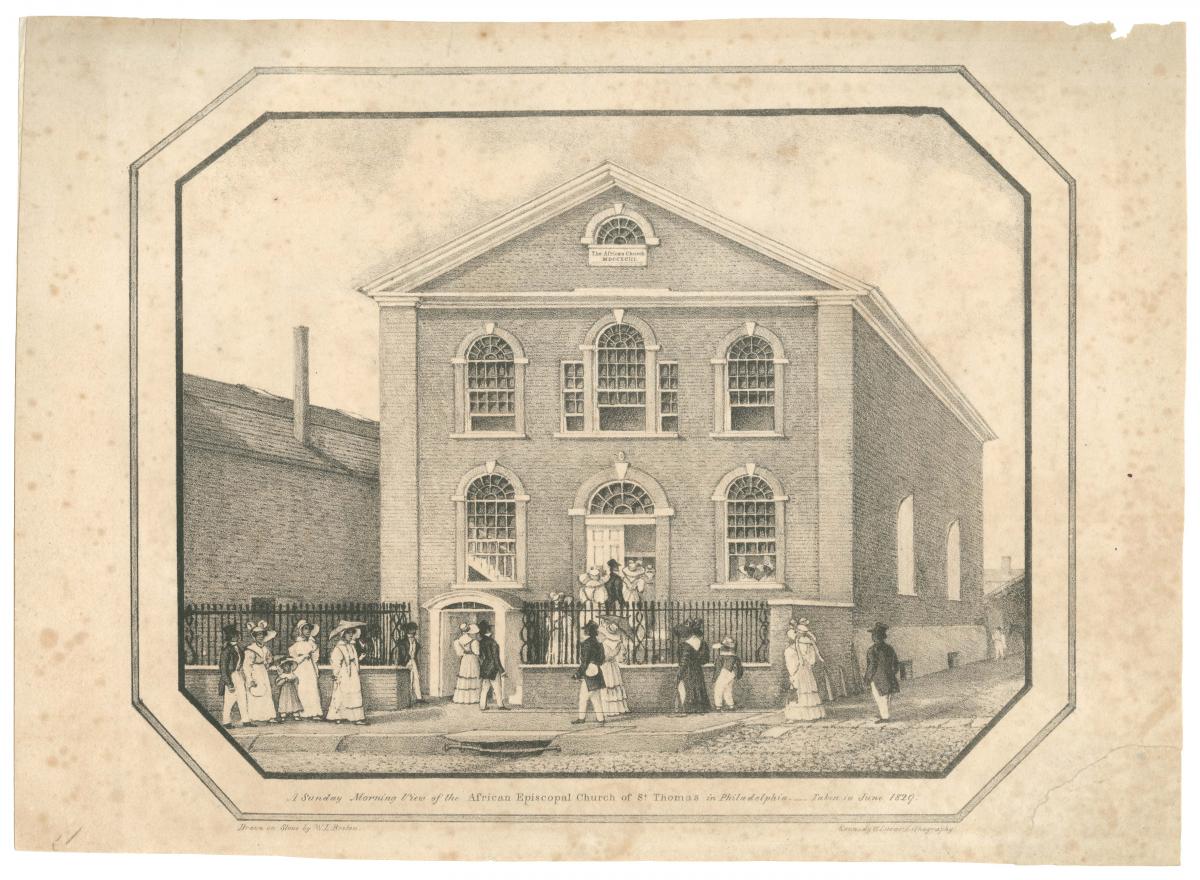

Even though they were the most despised people in the city, black Philadelphians shouldered the moral responsibility of aiding their neighbors. When they learned about the mayor’s plea for help, members of the Free African Society—an organization founded in 1787 that emphasized self-determination by choosing the name “African”—volunteered their services. Two clergymen, Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, cofounders of the African Church of Philadelphia (later renamed the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas), took the lead. When they visited City Hall, the mayor responded enthusiastically to their proposal. He even agreed to free black prisoners in the Walnut Street Jail— most of them confined for fleeing racial bondage—if they would help save the city.

"A Sunday Morning View of the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Philadelphia.—Taken in June 1829," by W. L. Breton. Historical Society of Pennsylvania Medium Graphics Collection.

Jones and Allen, along with William Grey, another leader of the Free African Society, placed ads in newspapers announcing that black Philadelphians stood ready to care for the sick and collect and bury the dead. “Sensible that it was our duty to do all the good we could to our suffering fellow mortals,” Jones and Allen noted, we “set out to see where we could be useful.” In groups of two, they walked the streets every day, stopping to see who needed help. For the next several months, African Americans, both free and enslaved, cared for the stricken, carted the ill to the hospital and the dead to the cemetery, organized workers to dig graves, and buried the dead. They also acted as constables: patrolling the streets, guarding abandoned properties, apprehending looters, and keeping order amid chaos. For the first time in history, the black community wielded enormous public authority in America.

Jones, Allen, and Grey worked tenaciously themselves and supervised a large group of others willing to help. They followed up after Dr. Rush, visiting 100 sick people a day. Nursing is particularly beneficial to yellow fever patients, since hydration is one of the keys to recovery. Without regular water, most infected people die.

Black volunteers likewise helped transform colonial lawyer Andrew Hamilton’s Bush Hill estate from a private mansion to a hospital. When authorities first assumed control of the building, it served primarily as a warehouse for sick people on their way to the grave. Lacking beds, medical supplies, food, blankets, doctors, and nurses, it quickly became known as a den of death. Many of the ill refused to go to the hospital during the early weeks of the epidemic, preferring instead to take their chances at home.

As black laborers and draymen steadily carted supplies and water to Bush Hill, Anne Saville, a member of the Free African Society, took over the nursing responsibilities, not only caring for individual patients but also organizing the staff, both blacks and whites. Under her direction, the hospital changed within weeks from “a great human slaughterhouse” to an institution in which most patients survived the disease.

During their duties, volunteers encountered horrifying scenes. They discovered hundreds of corpses alone in homes, reported Jones and Allen, “many of whose friends and relations had left them, died unseen, and unassisted.” Some lay “on the floor, without any appearance of their having had even a drink of water for their relief; others were lying on a bed with their clothes on, as if they had come in fatigued, and lain down to rest; some appeared, as if they had fallen dead on the floor, from the positions we found them in.”

The encounters with orphans were particularly heartrending. “We found a parent dead and none but little innocent babes to be seen, whose ignorance led them to think their parent was asleep. On account of their situation, and their little prattle, we have been so wounded and our feelings so hurt, that we almost concluded to withdraw from our undertaking.” Fear of catching the disease kept white neighbors and kin from offering any help, sometimes to the extent that it gave the “appearance of barbarity.” When possible, the humanitarian patrols “picked up little children that were wandering they knew not where, and took them to the orphan house.”

As they exposed themselves to the disease by going into homes around the city, especially those near the Delaware River, where the infection was most intense, many African Americans began to sicken and die. Dr. Rush had told them that yellow fever “passes by persons of your color.” However, except for those who had immunity from growing up in West Africa and contracting the disease during childhood, black Philadelphians possessed no biological resistance to yellow fever. To draw attention to the sacrifice of the African American community, Allen and Jones cited the increase in burials: “In 1792, there were 67 of our color buried, and in 1793 it amounted to 305; thus the burials among us have increased more than fourfold.” They concluded that just “as many colored people died in proportion as others.”

My own study, based on mapping all residents of the city during the 1790s, confirms Allen and Jones’s contention about the high mortality endured by black Philadelphians. The map “Yellow Fever Deaths 1793” shows higher and lower concentrations of deaths caused by the disease. In darker red areas, along the northern wharves and in a crooked line along Dock Creek, between 20 and 67 percent of the residents died. In the middle and western portions of the city, however, deaths were much fewer. The reason for this disparity was the range of the mosquitoes that spread the virus. The Aedes aegypti fly fewer than 100 yards in their lifetime, meaning that after they were introduced along the wharves by docking ships, they fed on people living within a few blocks of the Delaware River. Most free African American householders congregated in the middle or western edge of the city, the neighborhoods that suffered the least mortality during the epidemic. As black people volunteered to nurse and bury infected victims of the disease, however, they walked the streets near the wharves, exposing themselves disproportionately to the diminutive denizens of death. Their higher mortality resulted from their selfless commitment.

After the epidemic, many white people praised black Philadelphians’ invaluable service to the city. Mayor Clarkson and Dr. Rush both commended African Americans for their work. Other white citizens agreed. As Isaac Heston noted gratefully, “I don’t know what the people would do if it was not for the Negroes, as they are the Principal nurses.” Black volunteers had saved countless lives of white and some African American inhabitants.

Racism would devise its own interpretation, though. In his popular instant history of the epidemic, Mathew Carey accused black nurses and gravediggers of extorting money for their services. In virtually all epidemics during the previous century, caretakers had been criticized for ineptitude, thievery, and neglect of their patients. This attack was different, however, because it was also racially based. Black leaders were appalled to see their community excoriated in one of their finest hours. If this was the reaction to their heroic sacrifice, then what hope did they have for gaining acceptance and some measure of equality from the larger white community?

Outraged, Allen and Jones responded to Carey’s censure, writing a remarkable pamphlet, A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, during the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia in the Year 1793. The document provided an extraordinary eyewitness report of the conduct of one of the earliest free black communities. Even more important, it also publicly articulated the anger of many black people toward Carey specifically and to the wider institution of slavery in general. These feelings had rarely, if ever, found their way into print in early America.

Since Carey’s account praised Jones and Allen by name, the two ministers easily might have decided not to reply to his criticism of other African Americans. Their heated response indicates that they identified deeply with their community, believed they needed to defend its reputation, and desired to establish an African American voice independent of the control of whites. Carey’s critique also required a response because it undermined arguments that the behavior of blacks during the epidemic demonstrated their rights to equality and full citizenship.

The epidemic thus provided the first platform for black Americans to critique slavery in a public forum. Jones and Allen pointed out that slaves were not content with their lot, contrary to what many whites believed. Were “we to attempt to plead with our masters, it would be deemed insolence,” the authors explained. “We do not wish to make you angry, but excite your attention to consider, how hateful slavery is in the sight of that God, who hath destroyed kings and princes, for their oppression of the poor slaves.” Jones and Allen also warned whites of the danger inherent in keeping people in bondage. North American slaves, like their contemporary counterparts in St. Domingue, might rebel.

Jones and Allen addressed other African Americans in their pamphlet as well. As Christian ministers, the authors exhorted slaves to take solace in religion and to love their masters regardless of their misdeeds. Individuals in bondage, they urged, should try to convince their owners to grant them an opportunity to gain freedom. The two ministers, along with thousands of other enslaved persons, had achieved their liberty through self-purchase or individual manumission during the earlier decade. They advocated the same avenue for others.

Regardless of Carey’s criticism, the laudable behavior of African Americans during the 1793 epidemic helped soften the racial attitudes of white Philadelphians during the 1790s. “We have been beholden to the poor; to the despised blacks, for nurses to attend the sick,” read the report of the Committee to Alleviate Suffering, “as if Providence were determined to convince us that they are equally the objects of His care, with ourselves.”

Still, the larger society ultimately refused to embrace blacks as either citizens or equals. Carey’s original criticism, coupled with the mortal evidence that blacks did not enjoy a special immunity to yellow fever, discouraged many African Americans from attending the sick in subsequent epidemics in the city during the next decade. As discouraged black people withdrew from the fight against the disease, the city’s mortality rose even higher during subsequent outbreaks.