Google “Philadelphia & boycotts” and the search engine returns references to the Starbucks boycott that followed the controversial spring 2018 arrest of two black men waiting to meet a business associate in one of chain’s cafes.

Boycotts of merchants and consumer products, however, have a long history in Philadelphia, stretching back to the city’s own version of the Tea Party in 1773. The use of economic boycott as a form of protest against racism also has a history in the city. In the 1960s, boycotts were an effective way of getting the attention of employers and producers to change employment practices.

Flyer calls for a boycott of A&P until the store employs more black people, circa 1966-1971

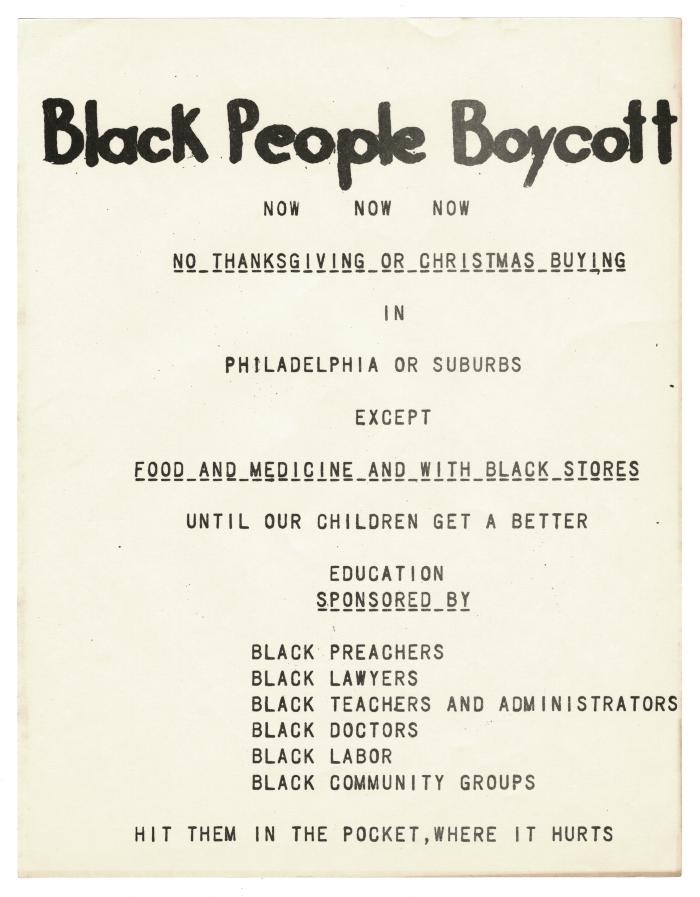

This buff-colored flyer from 1963 in the Thelma McDaniel Collection at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania announces a boycott of A & P grocery stores in order to encourage the chain to hire African Americans to work as cashiers, warehouse workers, and supervisors. Other flyers in the Collection request that people not shop in stores owned by whites during the Thanksgiving and Christmas seasons, both to change employment practices and to support better education for African Americans. The leaders of the movements are listed as “colored preachers of Philadelphia and Vicinity” and “Coordinated Citizens Concerned.”

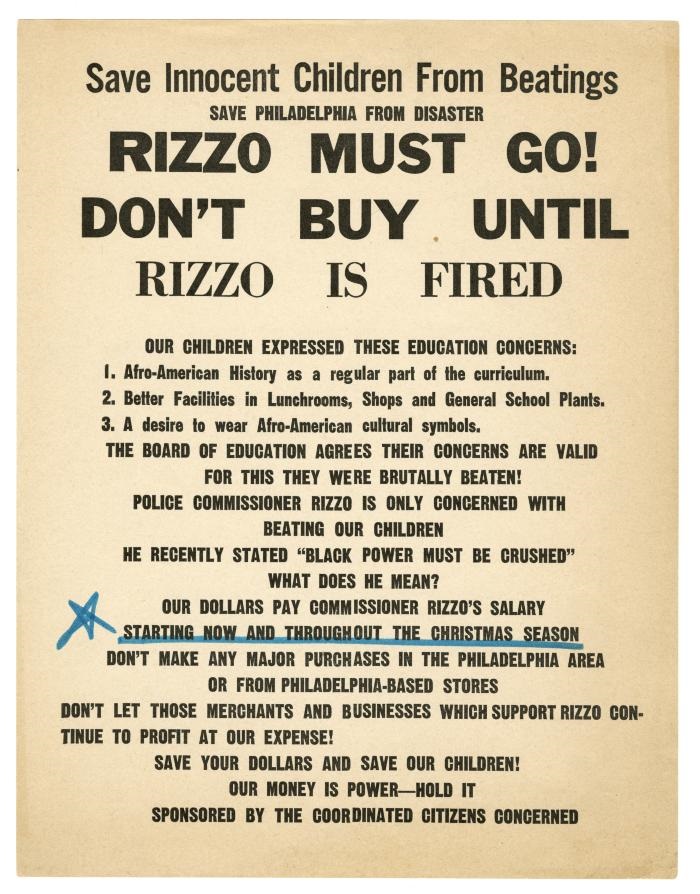

Boycott flyer singles out then Philadelphia Mayor Frank Rizzo

African American ministers were at the forefront of the economic boycott movement in Philadelphia. Beginning in 1960, a loose band of ministers began to advocate for “selective patronage campaigns” to pressure businesses into hiring African Americans in skilled and management jobs. Just increasing the numbers of people of color in a work force was not enough; the jobs had to offer a way out of poverty. The group first targeted Tasty Baking Company, the Gulf Oil, A & P and over 300 other companies in Philadelphia. According to an article in the Philadelphia Tribune from May 29, 1962, this “best unorganized organized group in America” was able to negotiate new hiring practices once companies were hit with an active boycott, or even the threat of one. At least 2,000 skilled jobs were opened to African Americans. This change came because an estimated one-quarter of the city’s citizens did not buy Breyer’s Ice Cream, Sunoco Oil, Tastycakes, and other groceries.

Philadelphia was not the only city with this sort of organized economic protest, but it was influential. Leon Sullivan of Philadelphia’s Zion Baptist Church shared methods with Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference that inspired Operation Breadbasket in Atlanta, Chicago, and other cities. As one Philadelphia flyer stated, “Our money is power – hold it.”

Poster calls on black people to boycott in order to “Hit them in the pocket, where it hurts”, circa 1966-1971

References:

Countryman, Matthew J. Up South: Civil Rights and Black Power in Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Univeristy of Pennsylvania Press), 2006

McDaniel, Thelma. Thelma McDaniel Collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania