As we were preparing for the HSP Martha Washington Potluck a few weeks ago, Director of Conservation Tara O’Brien and I were brainstorming about what cookware items would have commonly existed in early American kitchens. When one of our reference librarians, Ron Medford, overheard our conversation, he mentioned that he knew of some old cookware catalogs... in box TQ.40. Intrigued by Ron’s coincidental knowledge of some forgotten material that might answer our questions, Tara and I immediately went on a hunt for it in our archives. What we found in mysterious box TQ.40 was a collection hardware, home furnishing, and cookware catalogs and magazines that would make any historian smile because some bit of social and cultural history is waiting to be unpacked on nearly every page. I am extremely excited to share three items with you: an 1882 merchant catalog from the Lancaster homegoods company Steinman & Co as well as an 1882 magazine and 1977 catalog from the Philadelphia department store Strawbridge & Clothier. While these catalogs and magazines don't exactly lay out an entire history of American cookware in their pages, an examination of their representations of cookware and cooking reveal historic differences in advertising that stand in stark contrast to modern ads today. Please reference the photo album in the top right hand corner of this blog post as you read!

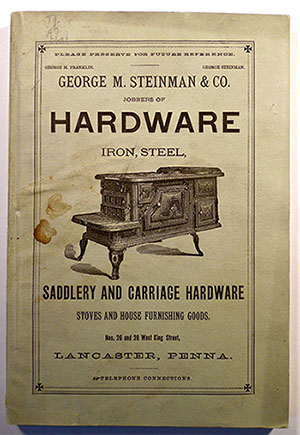

Steinman & Co. Illustrative & Descriptive Catalogue of Hardware, 1882

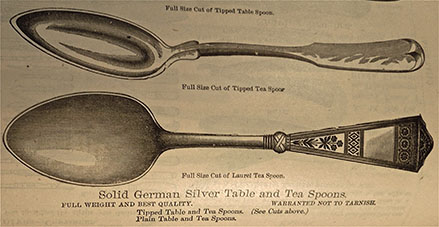

Flipping through this catalog for the first time, I was so captivated by the detailed pictures and descriptions of cookware that it took me a few minutes to see another jarring difference between this 19th century advertising and its modern counterparts-- there are no prices to be found anywhere on the pages! This was very odd to me, how could you expect a customer to purchase an item, if they don’t know the price? The answer slowly started becoming clearer to me while I was looked at the illustration of some spoons below:

View a larger version of this image in the photo album at the top right corner of this blog post.

If you look closely at this picture, you’ll see that the spoons are hand-drawn and not photographs. Although I was originally struck by the level of detail in the pictures, I hadn’t quite picked up on the fact that they were originally hand-drawn images that were then reprinted in mass for the booklets. Considering the amount of effort and attention that was paid to such a simple thing as spoons in this catalog, I became aware that creating this booklet full of thousands of items would have been a massive and expensive undertaking. This would explain why Steinman & Co. went to such lengths to recreate the items in their stocks without listing prices. Instead of continually bearing the cost of printing updated copies of the catalog with new items, it would have been much more practical and efficient to print one guide of items without prices which customers could use as reference over time to get an idea of what the company had to offer. Searching for concrete evidence in the pages of the book that would confirm my theory, I stumbled across an introduction that I had initially missed:

“This Catalogue is designed to assist merchants... (as) permanent reference and contains something of interest to every person. An effort has been made both by cuts and description, to give a clear idea of the most Salable Standard Goods and sizes in each department. It does not include all in stock, nor will that ever be possible, as new goods appear almost daily. It would also be impossible with so large a variety and the frequent changes, to keep in print our actual selling prices... we can assure you that our Prices are right...”

Although this introduction confirms my theory as to why the booklet does not contain prices, it ends up raising more questions. If the book is designed for merchants, then which stores were selling Steinman & Co. products? When a prospective buyer contacted the company for pricing did they have authority to negotiate prices? Were merchants from Philadelphia buying goods from this Lancaster company at wholesale prices and then selling them at a profit in nearby city stores? What kind of profits were they making? Were the Steinman & Co. catalogs sold to merchants or were they given away freely to attract business?

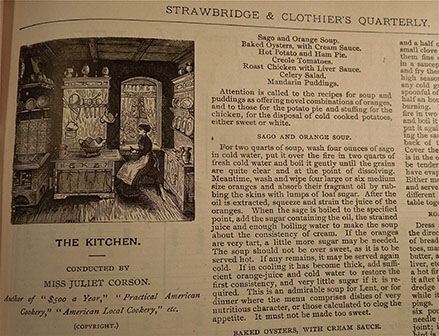

Strawbridge & Clothier’s Quarterly, Spring 1888

For those of you who might be unfamiliar with Strawbridge & Clothier, the department store is a giant in Philadelphia history that was founded by Quaker businessmen in 1868 and grew into a successful regional chain of stores over the following hundred years. As you can see from the cover above, Strawbridge & Clothier Quarterly labels itself as a magazine and is different from the Steinman & Co. catalog as well as the department store catalogs that we are familiar with today. This 1888 Spring issue, in particular, contains a whole variety of different articles ranging from short stories, fashion gossip, how to polish wood, and notes on nursing in addition to advertisements of desirable clothing and house materials for sale. Although the majority of the magazine is not focused on cooking or cookware, my favorite article is “THE KITCHEN,” which you can see below:

Written by Juliet Corson, who was well-known in the 19th century for her writing on affordable cooking, “THE KITCHEN” is a collection of recipes and tips for using fresh Spring ingredients on a budget. I suspect that some of the recipes, such as “Sago and Orange Soup” and “Creole Tomatoes,” would have been novel for many readers because they include imported ingredients like sago (a type of flour) and rice that could have only been grown in international climates. Corson seems to acknowlede the novelty of these recipes, when she writes: “... our menu will prove interesting to all our readers...” In addition to the recipes, the article also contains tips on determining the freshness of eggs, described by Corson as “that daintiest of all spring dainties.” I encourage you to experiment in your own kitchen and try out Corson's egg test by weight:

“Dissolve in a pint of cold water an ounce and a half of salt (about a tablespoonful) and float the egg to be tested in the solution. A perfectly fresh egg will sink to the bottom; and according to age, the eggs will rise in the water, a portion protruding above the surface when the egg is no longer prime for boiling, although it might be quite good for other methods of cookery” (Corson, 39).

Strawbridge & Clothier Home News & Savings, Spring 1977

Strawbridge & Clothier reached the height of its popularity in the 1980s and the image above is the cover of a 1977 company catalog. As you would expect, nearly a century-worth of advancements in technology make the advertisements in this catalog drastically different from the 1888 magazine. This is clear in the covers themselves, the older being black-and-white and originally hand-drawn while the second is a colored photograph. Changes in technology are obviously reflected in the cookware being advertised in the 1977 catalog as well.

This exploration of historic cookware catalogs and department store magazines not only gives us a glimpse into the local business history of Steinman & Co. and Strawbridge & Clothier, but also highlights the changing role of technology in American ads over the last century. Compared to today, when 3D online images and large department store chains make merchandise accessible, the 19th century catalogs and magazines discussed above seem antiquated. At the same time, it also seems that something special is lost from the hand-drawn images that give attention to the smallest of products. This leaves me with a question I have to ask: what do you think of these old catalogs and magazines in comparison to modern advertisements today?

Tell me what you think! Has something been lost from these historic cookware ads in modern advertising?

Learn more about this blog series, A Philly Foodie Explores Local History.