Ziryab Idir, an exchange student from Sciences Po Lille in France, transcribed French-language materials in HSP’s collection to produce this article.

During the turmoil of the French Revolution, many French people came to Philadelphia seeking asylum. Some immigrated for political reasons; they supported the monarchy or refused the mandatory military conscription. Others left France because of the economic recession and rampant financial insecurity. They came to the city of Philadelphia because it was the biggest and most prosperous city in America at the time—and between 1790 and 1800, it was the young nation’s capital.

French immigrants used ties in their old country to build businesses in their adopted country. Among these immigrants were the Besson Family. The Bessons probably left France for economic reasons, as they came from a rural French district negatively impacted by the Revolution. The Besson family archives, which cover two centuries of history from the end of the French Revolution to the mid-1950s, are preserved at HSP (Collection 1722).

The Besson family arrived in Philadelphia at the end of the 1700s. Their first documented presence was in 1803 when they received a certificate of accommodation from the French Republic establishing the reason for their travel. The document was certified by Charles Louis Fourcroy, a commissioner of the Department of Commerce of the French General Commission of Philadelphia.

Hailing from Haute-Loire, Antoine Besson settled in Philadelphia with his wife Marie Louise Vernier and their two children. He established himself as a ribbon merchant, recognizing that the United States’ upper class appreciated the accessory. Besson’s success developing his silk business stemmed in part from his nationality (French merchants were valued as symbols of elegance among wealthy Americans).

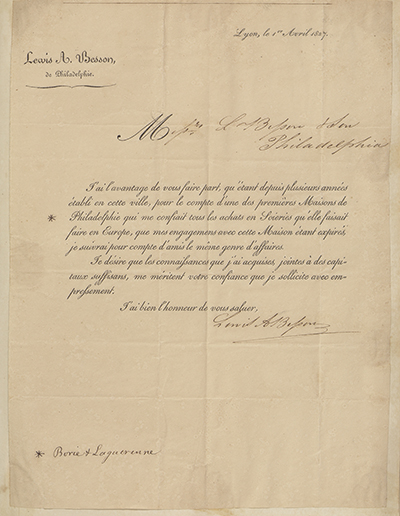

Besson’s son, Lewis, took his name from the Americanized version of the popular surname Louis. In an 1827 letter written from the French city of Lyon, the European capital of silk, Lewis, who worked for his father’s silk business, sought new partners for the family enterprise. In the letter, Lewis claimed that he was in charge of all the European importations of silk for one of the oldest silk shops in Philadelphia. In addition to these claims indicating the social and economic ascent of his family, Lewis’ letter was typeset, which demonstrates that he had access to resources.

In this letter dated April 1, 1827, Lewis Besson seeks new business partners and underscores his international background and personal wealth to attract interest.

The family’s documents also underscore how they integrated socially in the United States. Beginning with Antoine, many male members joined the Masonic Lodge of Philadelphia and studied at the University of Pennsylvania. Their family letters gradually shifted from French to English.

Following Lewis’ death, there were no further exchanges between Besson family members and Europe and no additional mentions of the silk industry.

The Besson family’s papers are a vivid example of an immigrant family using their background to succeed while embracing their new national identity.