This article was published in the spring 2019 issue of Pennsylvania Legacies (vol. 19, no 1): Epidemics and Public Health in Pennsylvania History.

by Jane Neff Rollins, MSPH

Does the thought of getting the flu scare you? Maybe not—but it should. Yes, today we have vaccines, antiviral medications, and chicken soup. Even so, CDC statistics show that influenza still kills up to 5,600 people in the United States every year. Imagine, then, what it was like 100 years ago when none of those medical interventions existed. In 1918 and the early part of 1919, influenza hit the entire world and may have killed as many as 100 million people. This pandemic was known popularly as the “Spanish flu.”

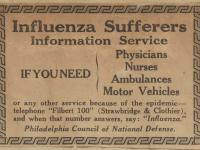

In Pennsylvania, as in other places worldwide, you couldn’t request a doctor’s house call because the dial telephone didn’t exist yet, and all calls had to be connected by an operator—many of whom were so sick from the flu that telephone exchanges were closed. Even if you could reach the doctor’s office, many physicians were either away fighting in World War I or were sick themselves. So many people died there weren’t enough coffins or gravediggers, and corpses piled up in the streets in Philadelphia and other cities until mass graves could be dug with bulldozers.

How Were Your Ancestors Affected by Spanish Flu?

The most direct effect of the epidemic on your family can be measured if one or more of your ancestors died during the Spanish flu epidemic. To determine this, you’ll rely heavily on death certificates and death notices or obituaries. Even if no one died of the flu, someone in the family may have been ill with it. You’ll likely rely on local newspapers in both cases.

Anne Hollingsworth Wharton obituary, 1924. Historical Society of Pennsylvania Society small collection.

Check your preferred genealogy database for all people who died between spring 1918 and spring 1919. If you don’t have a computerized database, consult paper records. Compare a given family in the 1910 US census with the 1920 listing. If someone is no longer there in 1920, perhaps he or she died in the flu epidemic. Obtain the death certificate and check the cause of death. Pennsylvania established statewide registration of deaths in 1906, so you should be able to find a death certificate for anyone who died in 1918–19. Pennsylvania death certificates for this period are available at FamilySearch for free and at Ancestry. When searching, set the year to 1918 ±1 year to catch those who died in the first quarter of 1919.

Keep in mind, though, that coroners during this period were overwhelmed. For public health reasons, bodies needed to be buried quickly, so a certificate may not have been issued. Death certificates for influenza victims also may not list influenza as the cause of death. Pneumonia is more likely to be recorded because influenza was not a reportable disease anywhere in Pennsylvania until Philadelphia resolved to make it reportable on September 21, 1918.

Obituary Sources

There were 1,800 newspapers published in Pennsylvania during the flu pandemic, many of which are digitized and available at the Chronicling America website. The newspapers are all word searchable, making identifying a relevant obituary or death notice much easier. Before starting your search by name, click on the “All Digitized Newspapers” tab to identify whether your ancestor’s hometown has a newspaper represented on the site. If not, identify adjacent towns and check whether newspapers from there are represented. The advanced search tab allows you to narrow your search by state (Pennsylvania), years (1918 to 1919) and phrase (enter your ancestor’s given name and surname as search terms).

Other good sources of obituaries during the epidemic include the Butler County, Pennsylvania, Obituary Index, 1810–2010, on Ancestry; the US and world newspapers collection on FindMyPast (leave the first/last name boxes blank, enter “influenza” in the “What Else?” box, and narrow results to Pennsylvania); and the State Library of Pennsylvania’s obituary links page. Finally, funeral homes can be good sources for this type of information. Try telephoning and asking whether they are willing to examine their historical records for you.

Research the Effect of the Spanish Flu on Families

Other clues may indicate that your family was affected by the flu. Do you have ancestors who were children during the 1910 census who had seemingly disappeared by 1920? It’s possible that they died and no death certificate was issued. But maybe they were farmed out to other relatives or to an orphanage because one or both parents died. You can look for court records that name a guardian for them or possibly find orphanage records. Did a family business appear in city directories leading up to 1918 but not afterward? Maybe the proprietor died from the flu, or had post-influenza syndrome including fatigue or Parkinsonism and could no longer manage the company. Look for ads to sell the business or bankruptcy filings in the newspaper.

Research the Effect of the Spanish Flu on Your Ancestor’s Community

Even if no one in your family fell ill with the flu, your ancestor’s community was definitely affected. Background information that may not specifically mention your ancestor can provide a picture of how their community was affected by the pandemic. For example, you may be able to find statistics for their town, county, or state. How many cases of flu occurred, and how many people died? How did local hospitals and physicians react to the epidemic in your area of interest? How many doctors and nurses were available, and how many were away serving in the military? Were tent hospitals set up? When was influenza made a reportable disease? Were public places (schools, churches, taverns) closed, and when? Were people required to wear gauze masks in public? Did police patrols remove bodies from homes because there weren’t enough undertakers, as happened in Philadelphia? Look for reports from your county or city’s health department on www.HathiTrust.org. Use search terms like “annual” or “public health report,” “monthly bulletin,” “municipal year book,” etc. You won’t be able to download entire reports unless you are associated with an affiliate institution, but you can download single pages or do a screen grab.

Newspapers can also help you research how the flu epidemic affected your ancestors’ community. Try the following search terms, either singly or in combination: influenza, Spanish flu/Lady, grip/grippe, pneumonia, coffins, mass grave, bulldoze, epidemic, lingering illness, quarantine, isolation, outbreak, fatal, mortal, succumbed, died, death, death toll, victims list, died of disease, Roll of Honor, closed/closure, cancel/cancelled/postponed.

General Genealogy Web Sites

The FamilySearch catalog has a few books of abstracts for Pennsylvania funeral home records for Blair, Fayette, and Lycoming Counties that cover 1918–19. Ancestry contains the Cemetery and Funeral Home Collection with more than 4,200 Pennsylvania records, and the Sons of Italy Mortuary Fund Claims database and Enrollment for Benefits List.

Pennsylvania-Specific Resources

Pennsylvania Newspaper Archive has a large collection of newspapers and offers an advanced search option that lets you limit by newspaper or by year range. On Periodical Source Index (PERSI), available through FindMyPast, you can enter “influenza” and the name of the town or county of interest as keywords. A recent search identified articles about the effect of the flu in Berks, Cumberland, Franklin, Indiana, Lancaster, Mifflin, Schuylkill, and Wyoming Counties.

The Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission has a webpage devoted to influenza epidemic records at the State Archives, and digitized records can be viewed online. Be sure to check out several sets of university yearbooks that cover the 1918–19 period (e.g., East Stroudsburg, Edinboro, Kutztown, Lincoln, Mansfield), the Diaries and Journals Collection within the manuscript collection, and Cadaver Receiving Books (influenza epidemic victims are identified in entries for October 1918 through December 1918).

If you are visiting Philadelphia in 2019, be sure to attend the Mütter Museum’s exhibit about the Spanish flu, Spit Spreads Death.

Jane Neff Rollins, MSPH, is a former infectious disease epidemiologist and current professional genealogist, writer, and speaker. She is an alumna of ProGen 29, Salt Lake Institute of Genealogy, and the Forensic Genealogy Institute. More information can be found on her website.