by Chris Damiani, Director of Public Programs

Through time, human understanding of the sky changed as scientific knowledge replaced religious interpretations of celestial phenomena; omens became comets, divine constellations became collections of stars. Yet space remained static and unmoving. Technological progress produced machines that permitted humans to traverse the earth by land, sea, and air. Despite these advancements, the impenetrable night sky loomed above, unwilling to give up its secrets.

The code was broken, however, when the U.S.S.R. launched Sputnik—the first artificial satellite capable of orbiting Earth—on October 4, 1957. The barrier had been breached, and the space age had begun. This scientific breakthrough occurred amidst the backdrop of the Cold War, which pitted the United States and the U.S.S.R. against each other in a global competition for political, scientific, and cultural dominance.

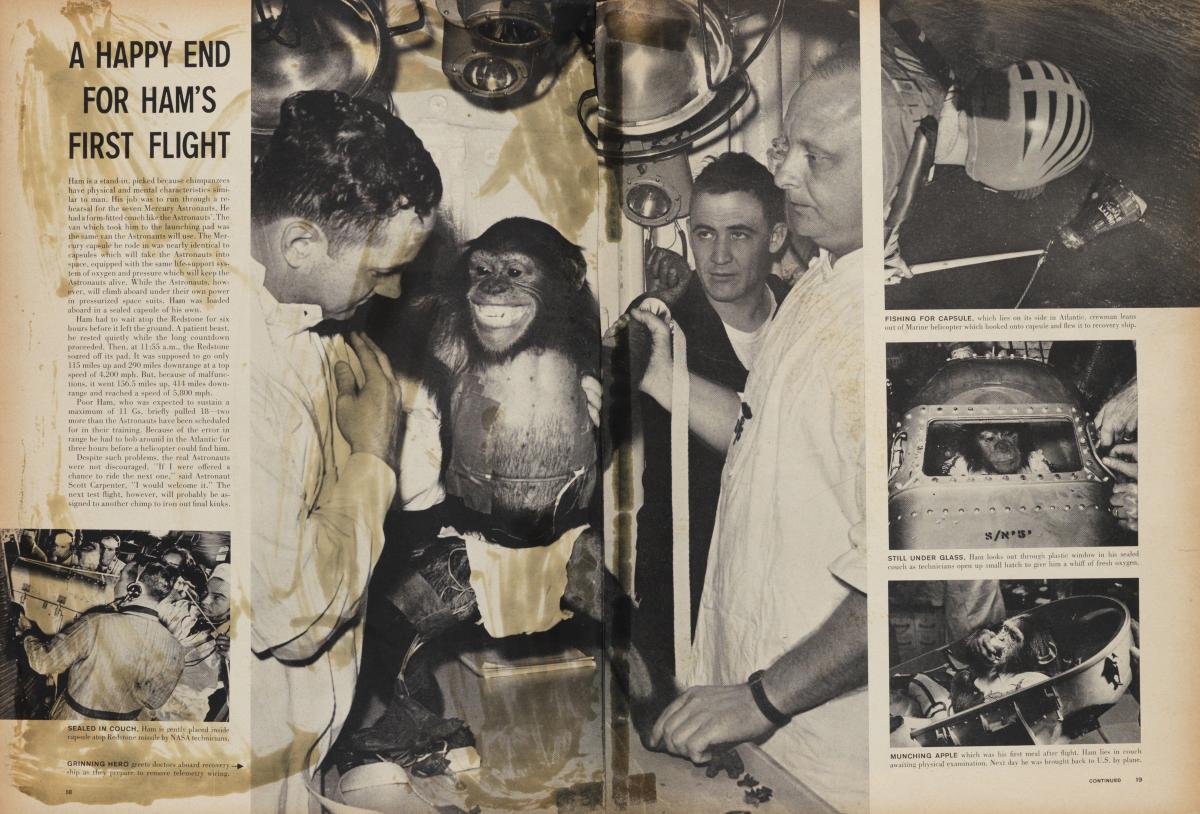

Following Sputnik’s launch, the United States began investing heavily in research technologies and sciences, resulting in The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which was created by an act of Congress on October 1, 1958. NASA soon launched its own satellite, Explorer I, on January 31, 1958. Meanwhile, the U.S.S.R. launched the first animal into space and the first man and woman into orbit, cementing its lead in what has become known as the “space race.”

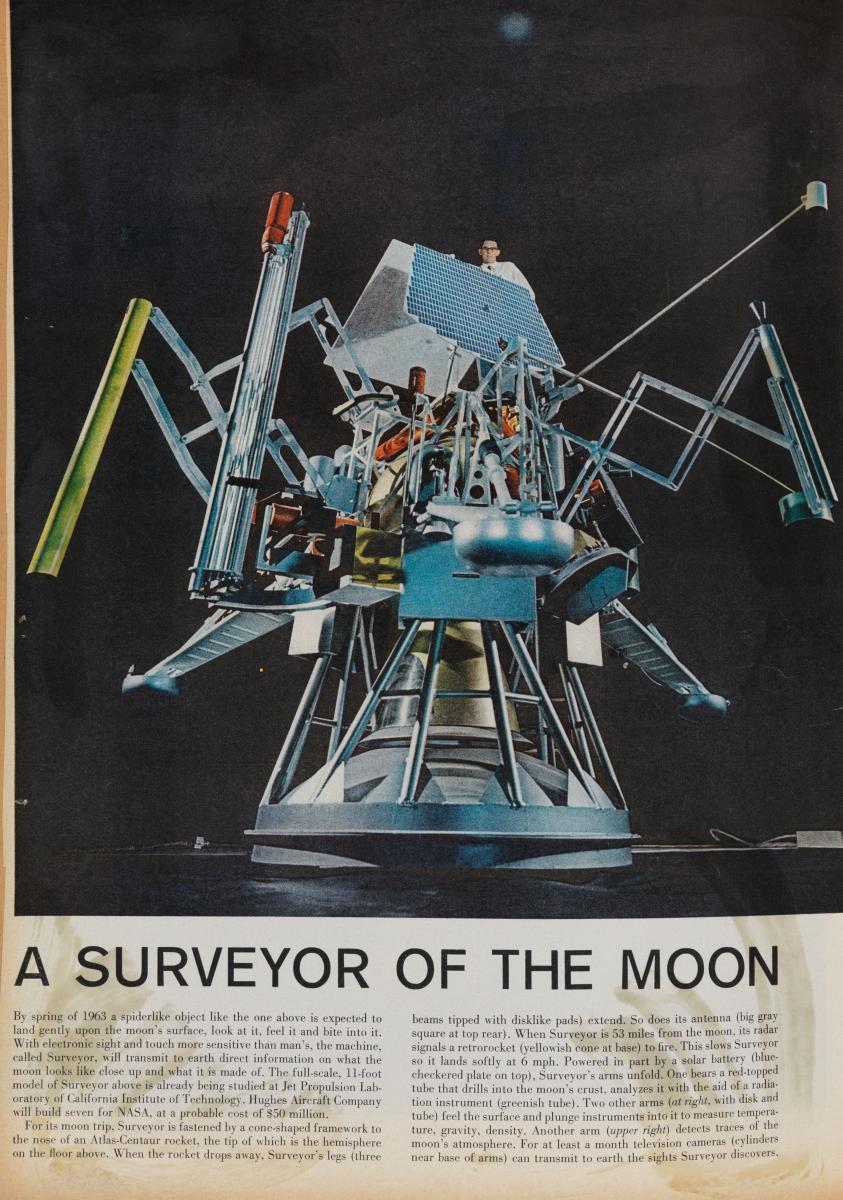

In 1961, John F. Kennedy famously proclaimed, “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth.” NASA pursued this objective throughout the 1960s, launching the Mercury and Gemini programs with the goals of learning how to move in space and dock spacecraft. These innovations paved the way for the Apollo program and brought Kennedy’s vision closer to reality. (These breakthroughs also influenced popular culture, inspiring shows such as Star Trek, Lost in Space, and Buck Rogers).

Despite NASA’s extraordinary technological advancements, the institution experienced its share of tragedies. A fire in the Apollo I capsule caused the deaths of three astronauts, Roger Chaffee, Virgil “Gus” Grissom, and Ed White II. Although a horrific loss, this catastrophe compelled NASA to redesign the spacecraft, and the Apollo program continued without further casualties.

On December 24, 1968, astronauts Jim Lovell, Frank Borman, and Bill Anders became the first humans to orbit the moon aboard the Apollo 8 spacecraft. Millions tuned in to see the first live images of the earth from the moon’s orbit. While the momentous occasion had been pushed forward by competition between countries, the astronauts saw their achievement as a win not solely meant for Americans but for the entire world. Perhaps the most famous example of this sentiment occurred a little over seven months later when Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins traveled to the moon on Apollo 11. On July 20, 1969, Armstrong became the first person to walk on the moon and uttered the famous words “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

If you had asked the average person 50 years ago where we’d be in regards to space exploration, they’d most likely have answered that we would be living on the moon. Due to political and socio-economic factors, the last manned mission to the moon was in 1972. Now, there is a renewed public interest in space exploration—fueled by Hollywood movies such as The Martian, the most recent images from Pluto from the New Horizons spacecraft, and new discoveries such as the potential for life on Saturn’s and Jupiter’s moons. NASA's mission has been re-charged with a fus on exploration and discovery and is currently planning manned missions both to the moon and to Mars.

Related Collections at HSP:

- Randolph Family Papers # 4234 - Contain a Scrapbook of clippings regarding the Space Race

- Chamber of Commerce Records # 1997 - NASA Correspondence and related

- Balch Institute Political Ephemera Collection # 3472 - NASA Photographs from Early 1970s