by David Barnes

This article was published in the spring 2019 issue of Pennsylvania Legacies (vol. 19, no 1): Epidemics and Public Health in Pennsylvania History.

Everyone says the Lazaretto is haunted. Why wouldn’t it be? It was a quarantine station and hospital for nearly a century. Ships, cargo, sailors, and immigrants were detained there, sick people were treated there, and many died there. Hulking and empty, built in 1799 and awaiting restoration, the Main Building certainly feels spooky. Volunteer firefighters on the night shift across the way say that a female figure used to appear periodically at a second-story window. Others say they’ve heard disembodied voices telling them to leave, or children crying out for their parents. Tales of apparitions go back decades.

I have never believed in ghosts. To my mind, the Lazaretto is just full of stories. There’s the story of Dr. Thomas Jefferson Perkins Stokes, the quarantine physician who was prosecuted for dereliction of duty in 1853 after he allowed a ship to proceed to the city, where it allegedly ignited a yellow fever epidemic. There’s also Tobias Smith, a mischievous 11-year-old orphan who was accused of starting a yellow fever outbreak in 1805 by illegally visiting ships under quarantine and returning to the city. And Mary Riddle, the widow who saved the Lazaretto from chaos and despair in its darkest hour, when an 1870 outbreak of the same disease engulfed the station, killed its principal officers, and spread upriver into the city of Philadelphia yet again. Then there’s Mary Ann Ganges, the nine-year-old girl who was captured and enslaved in West Africa, then freed as soon as she arrived in the United States and indentured as a domestic servant to the quarantine master. The place is positively saturated with stories. They are stories of pain and sickness, of fear and despair and death. They are stories of separation, of longing, of hope and healing and survival. If you listen carefully, you can even hear 21st-century echoes of distant 19th-century voices: immigrants calling out for medicine, food, shelter, opportunity; nativists fearing what the immigrants might bring with them; warnings of yet another epidemic imported from overseas; calls for vigilance— always more vigilance—against shadowy foreign threats; and patients and caregivers seeking healing in the midst of suffering and death.

Maybe that’s just another way of saying it’s haunted.

Yellow fever struck Philadelphia four times in the 1790s with devastating fury, killing upwards of 11,000 residents in the nation’s capital and largest city. Desperate to stem the deadly tide, the city’s newly established Board of Health replaced the old quarantine station at the mouth of the Schuylkill with a new, larger outpost farther downstream on the Delaware River at Tinicum Island. Doctors were bitterly divided over whether yellow fever spread contagiously from arriving ships or originated locally in accumulated filth. The Board of Health resolved both to clean up the city and to intercept incoming vessels at the Lazaretto. From 1801 to 1895, ships, cargo, and passengers were inspected and occasionally detained at Tinicum Island before being permitted to proceed to the Port of Philadelphia. Hundreds died at the Lazaretto; thousands more survived shocking shipboard conditions to begin new lives in a new land.

When I first laid eyes on the Lazaretto 13 years ago, I was completely unprepared for what I saw. What does a “quarantine station” look like, anyway? I imagined a homely utilitarian warehouse, half-ruined and crumbling into the river. After pulling my car over next to the fence on Second Street in Essington, just a couple of miles from the airport, in a riverside neighborhood of small industrial sites and modest working-class homes, I peered across a five-acre lot of patchy grass. There were a few decrepit boats scattered around the field on rusting trailers. Looming beyond, as if still standing silent sentry over the riverfront, was what looked like a huge red-brick Georgian manor house. My eyes widened. This place was BIG, I thought. Not just big, but grand. Stately.

I found an opening in the fence and walked toward the Main Building. Up close, the signs of age became more apparent. Patchy pointing in the elegant Flemish bond brickwork and leaning pillars on the long colonnaded portico testified to years of disuse. An intricately detailed wrought-iron gate, three smaller empty outbuildings, and the repurposed Lazaretto physician’s house (now the Riverside Yacht Club) hinted at a once larger campus of differentiated functions. Even with the jets taking off overhead, the vista across the slow ribbon of river to the forest of Little Tinicum Island struck me as weirdly bucolic. My head swam with questions: Why so big? Why so stately? Why here, of all places? And most of all: What went on here? I have been hunting for answers ever since.

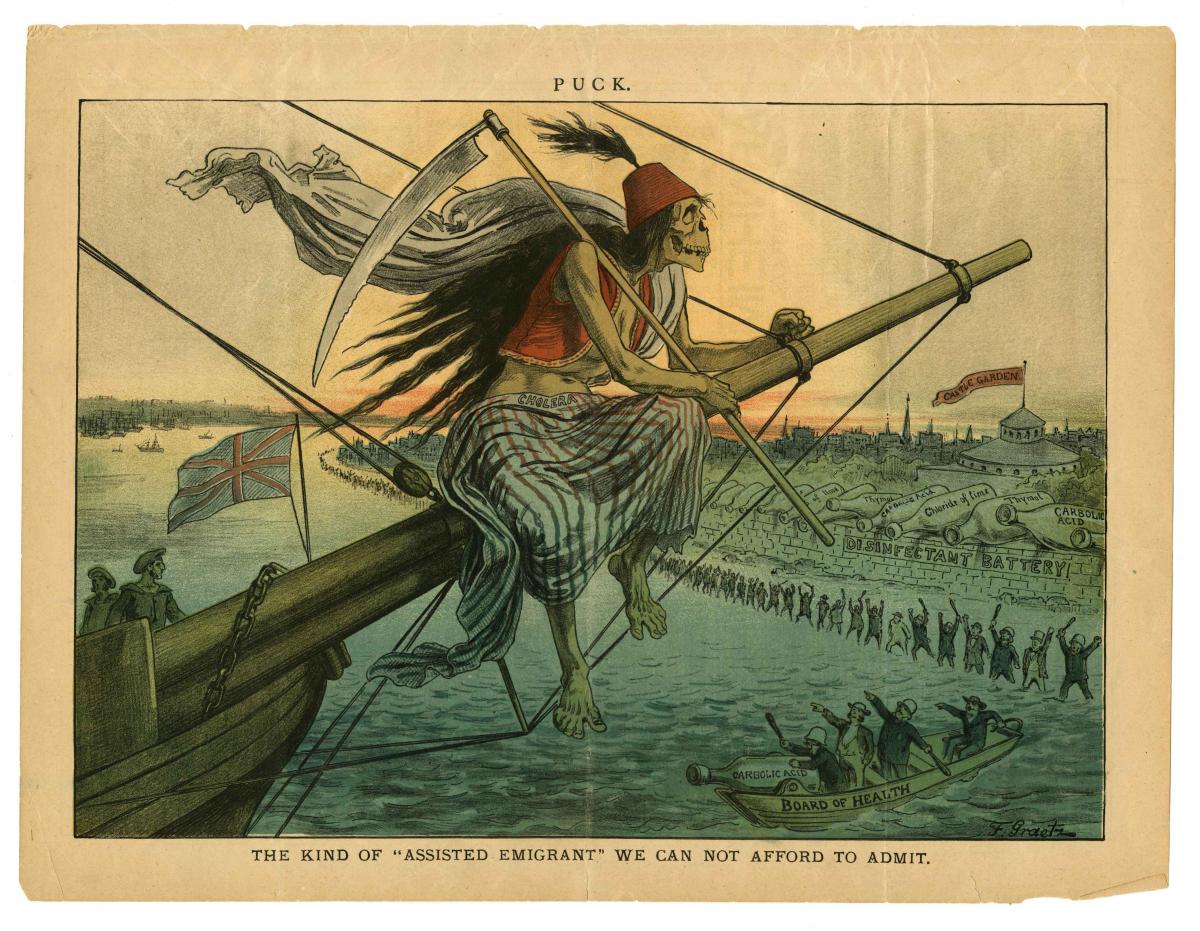

“The Kind of ‘Assisted Emigrant’ We Can Not Afford to Admit,” cartoon by Friedrich Graetz, published in Puck, July 18, 1883. Balch Broadsides: Satirical Cartoons.

At the Philadelphia City Archives, the first piece of paper I saw took my breath away. August 1, 1801, the first surviving entry in the minutes of the Board of Health after the Lazaretto’s opening earlier that year: “A communication was received from the Resident Physician stating the arrival of the Brig Adventure . . . from Liverpool, with 102 passengers, 53 of whom died on the voyage, and the remainder with the crew, except the Mate, are all sick. Therefore Resolved that the sick be immediately removed to the Hospital, and the well, if any, be provided with tents back of the Lazaretto, where they are to be supplied with every necessary suitable to their health & comfort, and the vessel to be detained, untill she has been thoroughly cleansed & purified.”

I was hooked.

Years of research later, when I visit the Lazaretto, I hear stories wherever I turn. I walk up to the gate, admiring the ironwork, and I hear the voices of the Woodburys, a lonely wife and her seafaring husband, separated only by that iron gate as they briefly reunited by permission of the Board of Health when Mr. Woodbury’s ship was detained at the Lazaretto in May 1803. I hear the stern indignation of the members of the board as they rebuked the Lazaretto physician and quarantine master for not policing comings and goings at the gate more strictly just a year after the Tinicum station’s opening. And I am reminded that security at the gate had a dual function: it guarded against the possible spread of disease beyond the Lazaretto’s fences, but it also played a role in the performance of public vigilance. The station’s officers and the Board of Health needed both to be vigilant and to seem vigilant. The efficacy of quarantine had a biological dimension and a social dimension. A traumatized and anxious public needed to know that its maritime quarantine was leakproof, just as today we need to know that public health and homeland security officials aren’t letting down their guard in protecting us from pandemics and terrorists.

Glass lantern slide of the Lazaretto quarantine station. Frances Anne Wister Lantern Slide Collection.

As I approach the river’s edge by the flagpole and the wobbly seaplane pier, I turn to face downriver. On a clear day, I can see as far as Wilmington, Delaware, 15 miles to the southwest. Behind the roar of jet engines overhead, I can hear the sailors’ boisterous shouting and the creaky rigging of the three-masted ships sailing toward Philadelphia, laden with coffee from Cuba, rags from Leghorn (Livorno) in Tuscany, and starving immigrants from Ireland. I hear today’s debates over the benefits and dangers of “globalization,” discussed as if it were a new phenomenon, and think of the Lazaretto’s early years, which were also the nation’s early years. Commodities, people, and news from the farthest corners of the world flowed past this place every day, into and out of the busy port city of Philadelphia.

Walking back toward the Main Building across the lawn, I hear the angry voices of the German passengers from the ship Rebecca, who arrived at the Lazaretto in August 1804. Waves of cases of typhus or “ship fever” from shiploads of mostly German-speaking arrivals overwhelmed the station. These were the “redemptioners,” poor immigrants forced to indenture themselves upon arrival to pay for their passage. There was no room indoors for all of the sick, much less for the healthy passengers undergoing quarantine, so they were housed in tents on the lawn. Resentment over their callous treatment during the unusually long voyage and frustration that their progress had been stalled so close to their destination boiled over into a riot among the Rebecca’s passengers, causing several hundred dollars’ worth of damage to the Lazaretto. Their harrowing journey first opened my eyes to the prevalence of human trafficking in the early settlement of the northern United States. Less remembered (and less extensive) than the horrors of the slave trade, the traffic in “voluntary” migrants nevertheless impoverished and killed thousands over decades. Networks of recruiters and middlemen, working in tandem with shipowners and sea captains, traveled parts of the European countryside scarred by war and economic dislocation, preying upon the hopes of the vulnerable. They promised the world and then systematically separated the migrants from their money and possessions, profiting every step of the way, until they took their final cut from the indenture in the United States. The shouts of the Rebecca redemptioners mingle in my head with the voices of the victims of human trafficking today, telling journalists about the lies they were told and the subhuman conditions in which they were forced to live.

Cartoon, A case of infectious fever (from “81 South Street, 4 doors from Callowhill Street,” Philadelphia) before the New York Board of Health, 1820.

I step up onto the portico and peer in through the ground-floor windows at the fancy millwork of the two front rooms in the Main Building’s central pavilion. The elegant adornments of the doors, windows, moldings, and mantelpieces signal that these were the most important and most public rooms at the Lazaretto: the office and the boardroom. Here the Lazaretto physician carried on the public business of quarantine, including writing his twice-daily reports; here members of the board held their meetings when they visited the station. I can hear the board and the doctor debating the delicate question of quarantine in the face of equivocal evidence. Enforce quarantine too strictly, and they risked detaining harmless vessels and damaging the prosperity of a bustling port. Open the doors too widely, and they risked allowing the ember that could ignite another epidemic to pass through. The central dilemma of quarantine amounted to a no-win proposition.

Continuing along the portico to the west wing of the Main Building—originally one of the two hospital wings—I look in the windows to the rooms where patients were once treated. I hear the bustle and chaos of those early typhus years and of the occasional arrival of a ship with yellow fever aboard. One or two nurses rushing about, tending to dozens of patients at a time, feeding and bathing and changing bedding and cleaning up excretions and administering remedies, the doctor stopping by in between inspections of newly arrived vessels. Patients calling out in pain, or simply in fear. Then there’s the quiet of sleep, or coma, or worse. But death visited these rooms surprisingly rarely. In the years for which records survive (1847–93), nine out of ten Lazaretto patients survived—even those with serious cases of fatal diseases like typhus and yellow fever, for which no specific and widely effective treatment existed at the time. How was this possible? I think the answer lies in the mundane chores that had the nurses rushing about so busily. Even today, in outbreaks of infectious diseases like Ebola hemorrhagic fever, most patients die from want of basic care, not expensive drugs. Food, water, clean linens, and rest were the “cures” provided at the Lazaretto. And as I look in the windows, I think 19th-century nurses’ and patients’ voices might contribute something valuable to our present-day conversations about “incurable” diseases. When the next epidemic comes, will we listen to the lessons of the Lazaretto?

When I stand on the portico of the Main Building, I look downriver, toward the Atlantic and the wider world beyond, and see the ships laden with goods and immigrants sailing to Philadelphia. I turn and look upriver, toward the city, and see the Board of Health and the anxious populace, anticipating and enduring and remembering deadly disease outbreaks. And I look inside the Lazaretto’s buildings to bear witness to the labor, the suffering, the deaths, and the survival of doctors, nurses, and patients over the years. Their experiences, buried in the archives, testify to the high-stakes drama of quarantine at the water’s edge, where potential tragedy always loomed in the background of everyday boredom and drudgery.

After opposition from Delaware County real estate interests shut the Lazaretto down in 1895, the old station became a country club called “The Orchard,” summer home of the Athletic Club of Philadelphia. In 1916, as the United States prepared to enter World War I, a few members of the club bought “flying boats” and opened what eventually became the Philadelphia Seaplane Base, which operated on the site until 2000. Today, Tinicum Township (which now owns the property) is restoring the Main Building in preparation for moving its municipal offices there. A preservation campaign is working to turn the Lazaretto into a site for recreation, education, historical exhibits, and events related to immigration and public health.

As I pass by the gate again on the way to my car, I hear one last voice in the distance. It’s a teenage girl, coming home from school. The Board of Health, which alone could permit people to enter and leave the Lazaretto grounds, resolved on July 14, 1806, “that the bound girl of the quarantine master be permitted to attend school in the vicinity of the Lazaretto.” That girl was Mary Ann Ganges, six years after her enslavement, liberation, and indenture. She was about 15 years old. Like a healthy passenger enduring a long quarantine, she was not quite free. I strain to listen, but I can’t quite make out what she’s saying.

These are the Lazaretto voices—and silences—that haunt me.

David Barnes is associate professor of history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the author of The Making of a Social Disease: Tuberculosis in Nineteenth-Century France (University of California Press, 1995) and The Great Stink of Paris and the Nineteenth-Century Struggle against Filth and Germs (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006).