The following article was written by HSP volunteer Randi Kamine and is being posted on her behalf. Many thanks to Archival Processor Megan Evans for helping prepare these articles for publication. To read the first part of this article, please click here or on the article's title in the right sidebar.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s all of Philadelphia was keenly interested in those inhabitants who were in sympathy with the Nazi regime. Local associations were looked at closely. News clippings, some of which are shown below, give the researcher a glimpse into how the citizens of Philadelphia reacted to what was a significant movement. A large collection of the news clippings at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania come from the Philadelphia Record, although there are also articles from the Philadelphia Bulletin and Daily News.

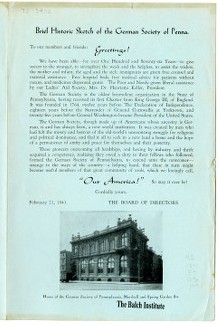

The German Society of Pennsylvania had a significant presence among American born and immigrant Germans. Founded in Philadelphia in 1764, it is the oldest and most prominent organization of its kind in the country today. In the 1940s, the society was located at Marshall and Spring Garden Streets. HSP has several documents that give the researcher an understanding of that organization during the 1930s and 1940s. A pamphlet produced by the German Society in February 1941 touts the society’s good works and emphasizes its patriotism toward the United States. The first page of this four page item declares, “Our America – So May It Ever Be,” and lists, “Some of the most prominent members of the German Society of Pennsylvania who have faithfully served their beloved City, State and the United States.”

"A Brief Historic Sketch of the German Society of Pennsylvania"

In 1964 Harry W. Pfund, head of the events committee at the Society, published a history of the Society that included the pre-World War II and war years. As presented in that report: “The epoch from 1914, when the German Society of Pennsylvania became 150 years old, to the end of World War II will stand forth as the most eventful one in the whole history of the organization. There is little doubt that it will appear to be the most tragic one.” Very little is told about the Second World War years. In fact, other than mentioning the decline in membership, and a line of succession of the presidency, there is no mention of society activities. At the end of World War II membership stood at 350 members, down from 624 in 1914.

The GSP tried its best to demonstrate its American patriotism during the war. In 1938 the society publicly condemned Hitler for his military aggression. But it was put on the defensive when in 1944 the society came under federal investigation. Officials claimed that the GSP had not contributed enough to charitable causes to qualify for tax-exempt status. This was despite the fact that members had contributed to five war bond drives in less than three years and in fact had given more than any other ethnic group in Philadelphia.

Attention was drawn to the society in part because some leading American Nazi sympathizers were influential society members. One board member who had an apparent connection to Nazi Germany was Kurt Molzahn, pastor of St. Michael’s and Old Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church on North Broad Street in Philadelphia. In 1931 he was elected to the GSP board of directors and served until his conviction, in 1942, for conspiracy to commit espionage. Molzahn was accused of being a propagandist of the Nazi regime. He often praised Hitler on his radio show as being a “good man,” although he denied being a follower of Hitler’s regime. According to trial transcripts, he became a German secret agent when he became involved with Gerhard Kunze, a Philadelphia Bund member who was also convicted in 1942 with violating the 1917 Espionage Act. Upon his arrest, Molzahn and his wife’s name disappeared from the records of the German Society of Pennsylvania. At the same time, the society did all it could to publicize its American patriotism. In 1956 President Dwight D. Eisenhower gave Molzahn a pardon for his espionage conviction.

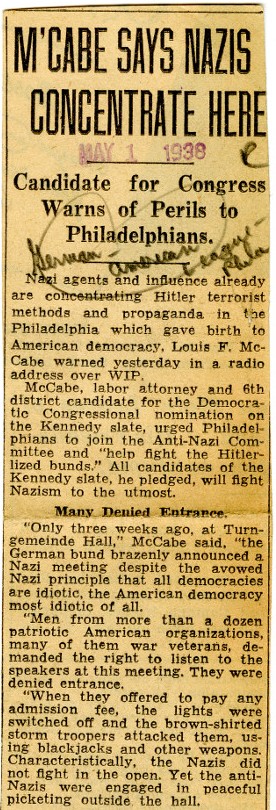

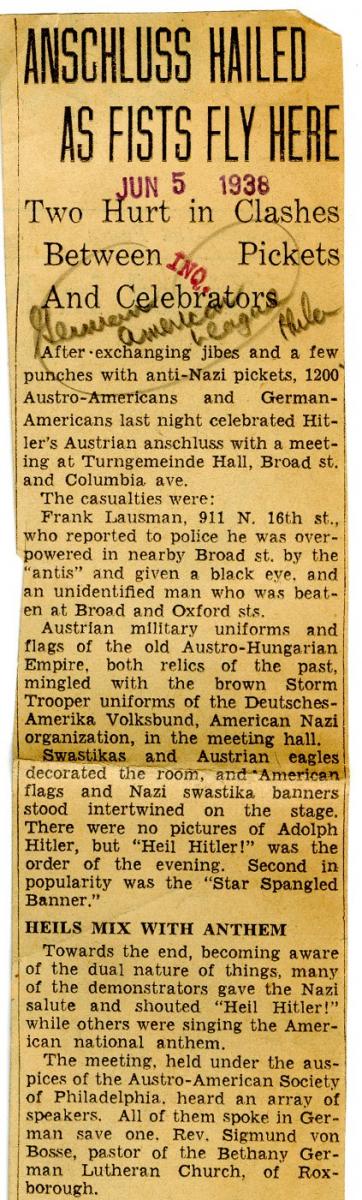

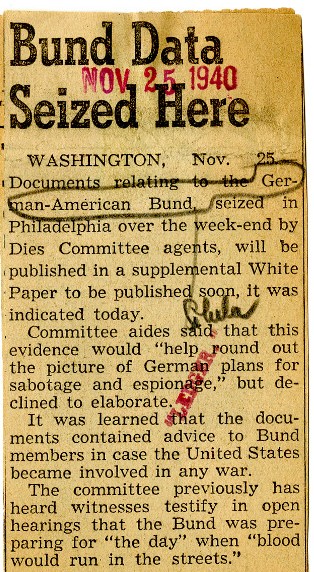

The Philadelphia Record news clippings morgue (collection 3344) is a large collection dating from 1918 to when the paper ceased publication in 1947. The clippings are housed in about 30 filing cabinets. Each cabinet contains small envelopes with clippings inside. At the present time, there is no finding aid for this collection. However, the envelopes are marked by subject. Fortunately, there are ten envelopes notated as “German-American Bund.” It is here we are able to read contemporary news articles about Nazi activity in Philadelphia in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

Coverage of the development of a Nazi presence in Philadelphia starts in July 1937. A Philadelphia Record article quotes Gerhard Wilhelm Kunzer, 31, head of the Bund’s Philadelphia “local” and editor of its weekly paper -- located at 3718 N. 5th Street, as saying, “At our meeting we “heil” our new country, the United States, our old country, Germany [and] the spiritual leader of the German people, Adolph Hitler.” Kunzer was born in Camden and lived in Philadelphia. He calls the German resorts/camps about to gain significant coverage in Philadelphia newspapers as “America’s white men’s camps.” He invites all “white gentlemen” to Bund meetings in the Liedertafel Hall at 6th Street and Erie Avenue.

The movement met Philadelphia residents’ resistance almost immediately. A February 21, 1938 article is headlined, “Shell Wrecks Philadelphia Nazi Bund. Homes Spattered with Shrapnel, Children Shell Shocked.” A bomb exploded in the early morning at Liedertafel Hall. Nazis drilled once a week at the Hall and leaders in the American Nazi movement often spoke there. Images below show reports on happenings around American Bund activity in Philadelphia in the year 1938.

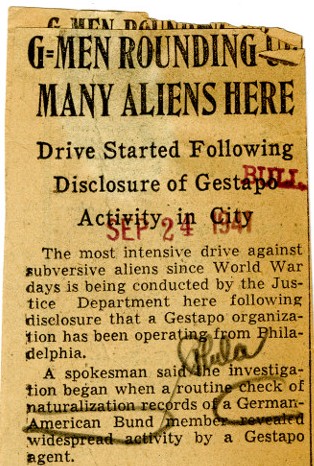

In 1940, 1941, and 1942 reports of “aliens” being “rounded up” along with their military and spying equipment dominated the news. On September 24, 1941, for example, an article is headed: “G-Men Rounding Up Many Aliens Here. Drive Started Following Disclosure of Gestapo Activity in City.” It goes on to say, “The most intensive drive against subversive aliens since the World War is being conducted by the Justice Department here following disclosure that a Gestapo organization has been in operation from Philadelphia.” According to this article, 150 aliens had been picked up each month in eastern Pennsylvania and southern Jersey since mid-summer. Some were held on immigration charges and some on anti-American activity.

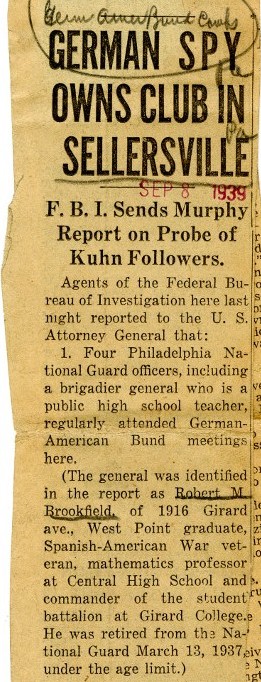

A camp in Sellersville, Pennsylvania, approximately 40 miles from Philadelphia, played a prominent part in news coverage of Nazi activity. There are over forty-five clippings describing the camp. It was at the Deutschhorst Country Club in Sellersville that Fritz Kuhn, head of the German-American Bund, made a famous “Hitler can lick the world” speech in 1938. Two thousand people attended, mostly Philadelphians. It was reported that the camp at Sellersville was owned by a known German spy.

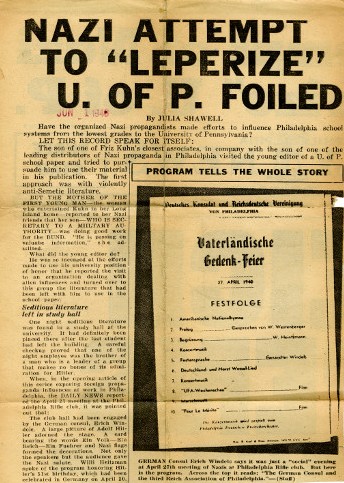

In 1939 a woman at the resort passed out leaflets with the heading, “The Dies Jew-Controlled Committee is an Anti-Gentile Inquisition.” In fact, attacks on Jews became more pronounced as the movement picked up steam. A report identified a printing plant in north central Philadelphia where pro-Nazi and anti-Semitic propaganda intended for national circulation was printed and stored. At a rally at an Andover, New Jersey camp, The New York Post reported in August 1940 that a proposal to tar and feather all Jews “brought a long, hearty demonstration.” Fritz Kuhn and Col. Charles Lindbergh were hailed as martyrs. Bund meetings were quite open about saluting the swastika, heiling German leaders, and singing Nazi songs.

The camps’ primary objective was to recruit German-American youths between the ages of eight and eighteen to Nazi ideals. Rifle practices were held, and the children routinely sang the Nazi national anthem with shouts of “ Sieg Heil.” Sellersville and Andover were not the only local rustic locations of Bund activity. On September 24, 1941 a news article states, “A spokesman said he could locate three or four Bund camps no more than 15 minutes drive from my Chestnut Street office over the Delaware River Bridge.” There were approximately nineteen children’s camps throughout the United States. The New York Times, the Philadelphia Bulletin, and the New York Post are also represented in the Philadelphia Records collection. There are also clippings from the Philadelphia Daily News. Then, as now, the Daily News had the most dramatic headlines and the most colorful descriptions of the goings on in Fascist communities, such as the article below:

Anyone interested in researching the history of the German-American Bund, Philadelphia during World War II, or Philadelphia 20th century immigration will find this collection a valuable resource. This collection of original documents adds to an understanding of an important part of World War II history. In addition, researchers interested in the House Un-American Activities Committee will find copies of the famous reports. And for many, the Philadelphia Record Photograph Morgue (Collection V07), as well as the Philadelphia news clippings collection will contain not a few surprises about Philadelphia history.