(This is the first of several blog posts on the letters of Peter McCall Keating, a doctor with the US Army who served in France during WWI before and during the United States' involvement in the war. The blog posts were written by HSP volunteer Randi Kamine.)

On occasion when processing a large collection, an interesting smaller set of documents emerges. This was the case when the McCall Family Papers (collection 4088) were being inventoried for preparation for a finding aid. A packet of letters written by Peter McCall Keating, called McCall, gives the researcher an insight into overseas activities practiced by the United States Army before the United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917.

Keating was born on July 21, 1884 and he died on February 20, 1959. He and his family were practicing Catholics and while he was in France he often mentions going to Church and attending a high mass. He requested that his mother send him a medal of Our Lady of Victory. He found comfort in that a priest was within call for him and “his chaps” when they got sick.

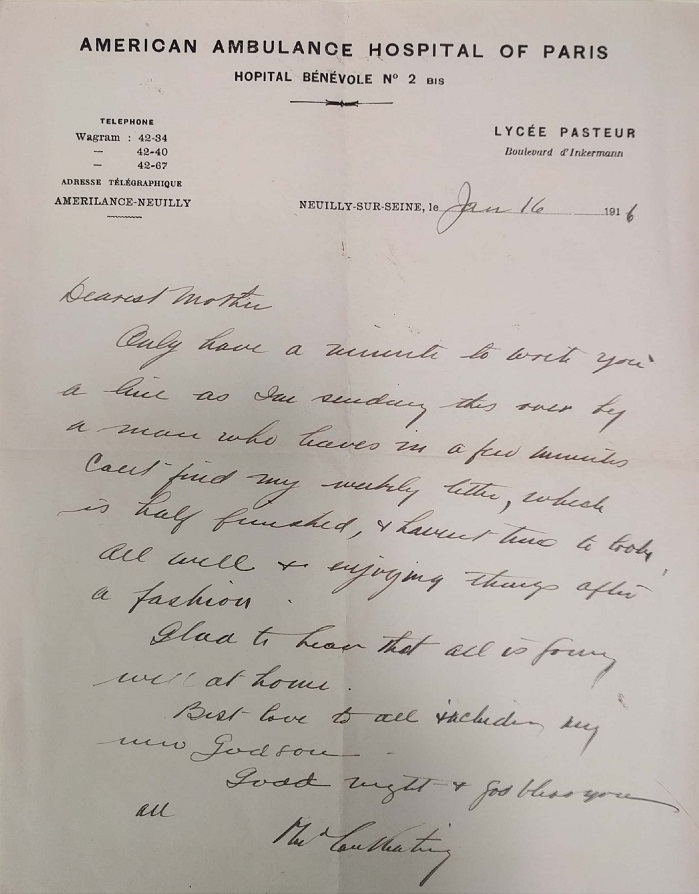

At the time he wrote the letters, he was thirty-two years old, an M.D., and held the rank of First Lieutenant, Assistant Surgeon in the United States Army. He was assigned to the American Hospital of Paris located just west of the city in Neuilly-sur-seine. Established in 1914, the Hospital was staffed by American doctors, surgeons and nurses. Its ambulance service helped over 10,000 allied soldiers. A school, the Lycée Pasteur of Neuilly-sur-Seine, served as a hospital and the base for an ambulance service.

There are seventeen extant letters written in France, dated from December 10, 1915 to June 21, 1916. There is also one letter with an “officers’ mail” postmark of December 31, 1918 in which Keating mentioned that he had been away from his family for two years, suggesting that that he either remained in France or returned to France later in the war. All the letters were addressed to his mother, Edith McCall Keating, who lived in Wawa, Pennsylvania. (Keating’s father, John M. Keating, M.D. had died in 1893.) The letters were intended to be read by all in Keating’s extended family.

The letters give a contemporaneous view of voluntary medical assistance given by the United States Army before it entered the war. Many of the letters written in 1916, before U.S. involvement in the war, have a breezy, casual tone. The 1918 letter, however, describes his experience in more serious terms.

As indicated in his first letter, and indeed in a recurring theme, he saw his experience as a bit of a lark. As a soldier, he did not leave his upper-middle-class origins behind, as indicated by his level of education and his primary interests. Despite his work with traumatized and injured patients, he was often bored, dwelling on the latest dinner and entertainment he enjoyed, and reflected very little on the larger scope of his situation.

The last letter in the collection, acting as a postscript to Keating’s letters, was written to Keating by a cousin from France in 1923. It is the most affecting of all the letters, revealing the experience of “a broken woman,” who had not been able to “force courage” to answer a previous letter due to the deaths of her son and son-in-law in the war.

McCall Keating’s work

On December 10, 1915, Keating noted that he would be leaving the hospital in Paris the next day to go to Campiegne, on the Oise River, sixty-four miles north of the hospital to

“experience Christmas within the sound of the guns – sort of a hollow mockery it seems and yet perhaps a little island of peace in the midst of a whirlwind of passion. With the never failing luck of the Keating, I, just when I rather want a bit of rest, am sent to that lovely old Chateau where the work is easy and the food and accommodations wonderful.”

He had “many pleasant things” to tell the family: meeting a charming young Irish girl, a tea party, and a very pleasant dinner with Keating cousins. (Apparently Keating knew many people who worked in the hospital, including relatives.) And he had the opportunity to see

“the finest specimen of French manhood tonight that I’ve ever seen. At least 6’4, weighed over 250—trained down to the limit—all artillery officer –with a face and head of a Viking and apparently didn’t know it.”

Keating was in Campiegne for two weeks. He told of the beauty of the Oise River in the north of France, the perfect weather and the delicious food. He wrote of the various duties he had as a physician in the field, but his responsibilities did not seem to weigh heavily on him. He traveled to several French hospitals where he applied dressings and performed operations “to the distant boom of the guns” but says that work was practically at a standstill. He saw only the victims of a “lucky shot,” and those were few and far between. Going from hospital to hospital was “a very pleasant drive.”

He wrote about the soldiers in the trenches, and a tremendous bombardment that lasted three nights. And although he claimed the bombing “doesn’t disturb my peaceful slumbers,” it was “interesting” to hear the heavy shock of the high-explosive shells bursting and the rat-tat-tat of the machine guns and the firing at will of the rifles. He noted,

“We have three chaps who are badly hit but are getting well, the fourth hit by the same shell died on the way from the trenches – the effect of a shell when it lands is pretty awful. The rest of the cases, some 55, are all recovering.”

Back at the hospital in Paris, he wrote, “Sort of a busy day all around – saw one good operation – my patient died tonight and now I’m in a quandary: how to find his family and give the message I promised to him to give.” Keating often seemed to exhibit insensitivity toward the victims of war -- usually by combining some horrible news with descriptions of his latest foray into fine dining or sightseeing.

One may speculate as to why he expressed himself that way. He was a doctor, so exposure to injury and death may not have been the trauma it would be for other people. Secondly, it must be remembered that he was writing to his mother. He showed great affection for her and his family and it may be that he simply wanted to play down the negatives so as not to distress her. Finally, his letters were censored so he may not have wanted to slow up his letters home.

Witnesses to the front lines confided in Keating. He spoke with a French officer who unburdened himself of his experiences. He told of the forty men under him who hadn’t unsaddled for a month, and at the end of that time the officer was ordered to take his men against a small troop of Germans. Only seven men started because only seven horses were still able to travel. The troop turned out to be a regiment and the French were in the trenches fighting for three hours before help came. In a subsequent letter Keating mused, “I suppose really though now we can see these “foreign races” in one way at their best – in another way it’s the worst time possible.”

Keating also gave a first person accounts of the battle field. He wrote:

"I never imagined before what a curious looking thing the country back of the trenches was. All around us are trenches zigzagging through the country line after line and all connected by other trenches zigzagging along so as to protect those walking in them."

Keating went on to describe posts set about twenty feet apart and strung with the “biggest barbs you ever saw” at every conceivable angle.

He observed the French Chasseurs in training and was duly impressed. The Chasseurs were cavalry troops ordered to jump trenches in advance of infantry, and Keating noted, “Well, if you’ve ever seen a trench and a barbed wire entanglement you know what a fool thing it is [to attempt].” He described the Chasseurs in action:

“The artillery first [took up?] the line between the trenches and back of the first line of Germans for some distance. Then the infantry went in . . . and then the Chasseurs. They did jump the first and second line trenches, but then they ran into a lot of low wire stretched about 6 inches above the ground …there were heavy losses.”

Still, Keating’s bar for excitement was quite high. He wrote, in the same letter, “I’ve seen rather few aeroplanes lately, so I have not seen much in the way of excitement in that quarter.”

Nonetheless, Keating did take stories he heard and the things he witnessed to heart. Despite his continuing to write about fine meals, concerts, and glorious weather, he was cognizant of the seriousness of what he was experiencing. He anticipated the United States’ entry into the war: “I’m afraid we may have trouble at home, and from all accounts, if we do get into this mess it may mean great unpleasantness at home.” This was written on January 14, 1916. A month later he hoped the war would never come to America, writing, “After the war is over it’s home for keeps, a comfortable fireplace and our own belongings, any old sort of [doctor’s] practice.”

Even though the U.S. was not to enter the war for another year and three months, letters were censored: “This letter can’t go for about 10 days –because well they don’t like letters that mention war and so this will wait and be escorted home by one of the men who are leaving,” he wrote. He told his family that his letters would become less newsy because it was not wise to talk too much of what one saw when outside of Paris. No photographs of anything he saw on the field were allowed.

By January 30th, the war had become more vivid to the Army volunteers. In Paris, a Zeppelin conducted a midnight raid on Paris, killing several people and wounding many more. Again there was an odd casualness to Keating’s report. Keating heard the bombs being dropped by the Zeppelin when he was at the theater. He wrote, “but anyway the Opera was good – in fact lovely.” And then the comment, “It’s rather ghastly this killing of women and children who are defenseless.” Another moment that may, to some, show a disconnect was his description of being at the Front, “not unlike the kids putting their tongues on a piece of brass on a freezing day: unpleasant but interesting.” One can at times be brought up short by Keating’s nonchalance in his coming face to face with the horrors of war.