Every Sunday, my parents bring home a copy of The World Journal Weekly (Shi Jie Zhou Kan), the Sunday edition of a newspaper circulated in the Chinatowns of the United States documenting everything from world events and economic news to articles addressing issues pertinent to the Chinese American community. I remember that these pages of colorful newsprint would litter the house, and for the longest time, I paid little attention to them. The few times that I did find them useful usually had more to do with their ability to serve as a great substitute for, say, Styrofoam packing peanuts.

As I was entering combinations of keywords into HSP's catalog, however, some entries I found soon made me change my opinion about those newspapers. For starters, I didn’t realize that the publications my parents read had counterparts dating from the 1890s—a bit silly considering the amount of time newspapers have been around (as opposed to, say, social media). And given that these were published with articles written and translated in both English and Chinese, my ability to peruse the contents shot up.

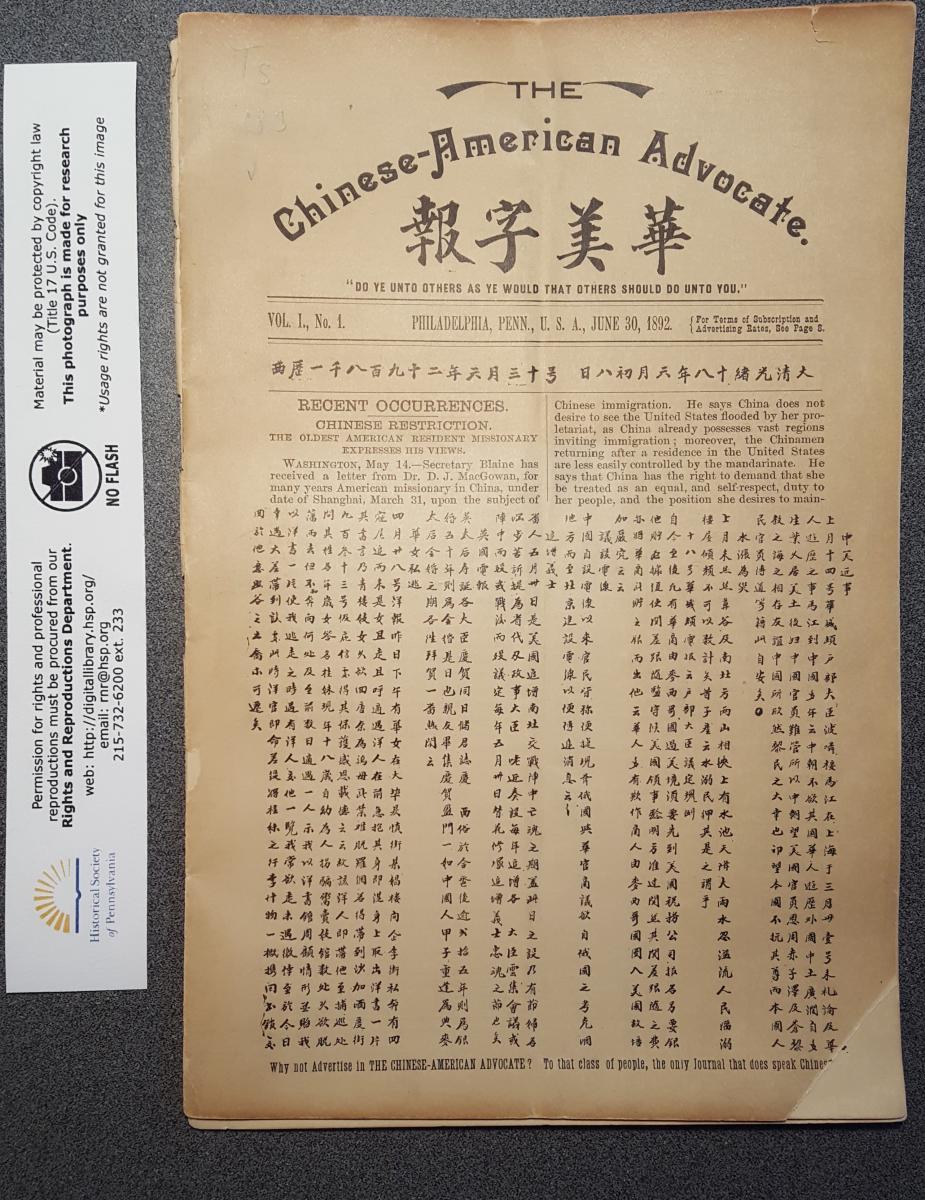

The first publication that caught my eye was HSP’s collection of The Chinese-American Advocate (Hua Mei Zi Bao), a bilingual series published and distributed in Philadelphia starting in 1892. While I only found the first two issues of the first volume, there was plenty of material to digest. As the newspaper's title and motto (“Do ye unto others as ye would that others should do unto you”) suggest, a large part of the publication’s aims were geared towards the community outside of Philadelphia’s fledgling Chinatown.

The first issue of The Chinese-American Advocate. Dr. Jin Fuey Moy, the editor of The Advocate, was one of the first Chinese in America to become a doctor. Dr. Moy practiced mainly in the Philadelphia area.

By the late 1800s, many Chinese on the West coast of the United States who remained after the California Gold Rush and transcontinental railroad boom began to migrate eastward to escape rising anti-Chinese sentiments. There, they formed communities in mostly urban areas and took jobs that incited little offence, such as opening laundromats and restaurants offering Chop Suey. Given the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the subsequent Geary Act of 1892 that prohibited further entry of Chinese into the United States, many of these early Chinese Americans were bachelors or men whose families were still in China. With few efforts made to integrate them into American society, these men and their enclaves became associated with rampant gambling and drug use.

This was the type of community that Dr. Jin Fuey Moy, editor of The Chinese-American Advocate, wanted to speak out for. In his introduction of the first issue of The Advocate, Dr. Moy appeals to his English-speaking readers, stating: “It is the purpose of this publication to be as substantially useful within the range of its influence as the circumstances will permit. While in a sense addressed to and for Chinamen, resident in America, it mayhaps will fall into the hands of many an American or English-speaking friend of the Chinese race, and to such we would desire to be helpful in their intercourse with those people, and enable them the better to accomplish the good they have in mind.”

The content of the publication itself also reflects this motive. While the newspaper is written in both Chinese and English, only a select number of the articles are actually translated into Chinese. Other pieces, such as that detailing with the escape of a Chinese girl from an abusive “work house,” are left un-translated and clearly appeal to the sympathy of an American reader.

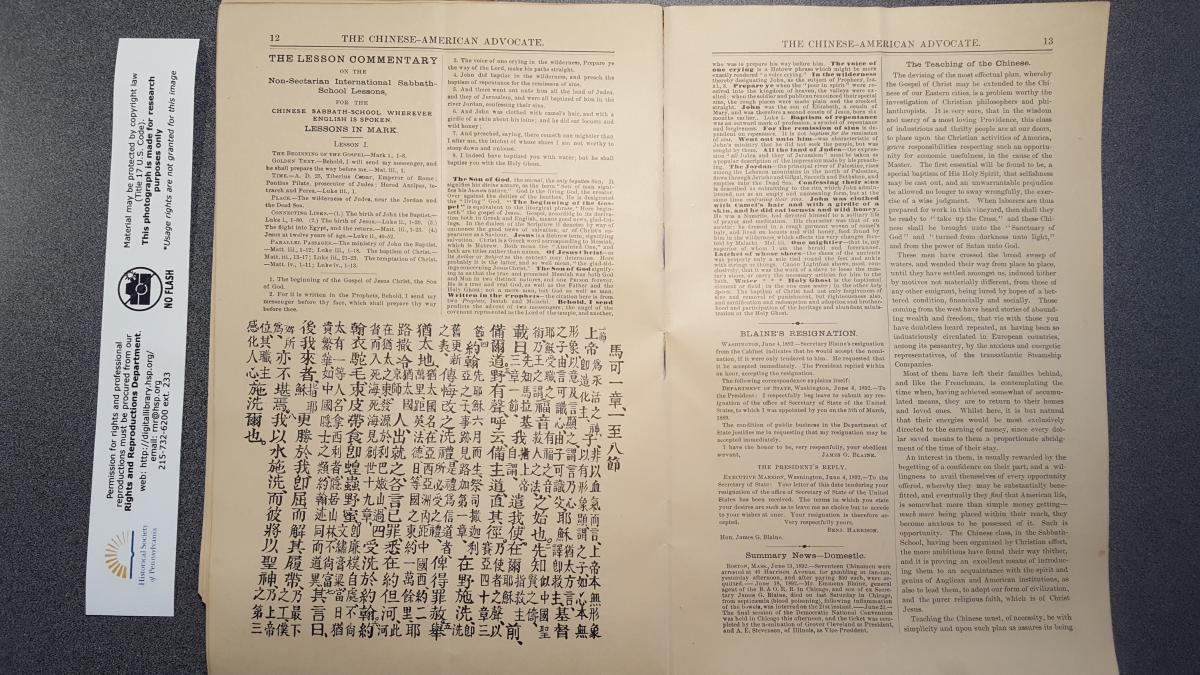

But this is not to say that Dr. Moy addressed little content to his fellow countrymen—in fact, what he does translate is quite crucial to the Chinatown community. Beyond news about China, Dr. Moy also included a translation of a Sunday school lesson in each issue, as religious bodies were one of the few institutions to reach out to Chinese American communities at the time. And, in the first issue, the centerpiece article includes a copy of the newly passed Geary Act of 1892 translated into Chinese. This is critical, for beyond just extending the ten-year effectiveness of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the Geary Act also mandated that all Chinese in the United States carry documents proving their valid residency at all times. Without these papers, they would be deported.

An image of a Sunday school lesson translated in Chinese in The Chinese American Advocate.

The Chinese-American Advocate is not the only publication to have served such a purpose in Philadelphia’s Chinatown. One of the other collections I found almost immediately when scrolling through HSP’s online catalog included several volumes of Yellow Seeds (Huang Zi Bao) published starting in 1972. This newspaper is also written in both English and Chinese. Like The Advocate, it focuses mainly on raising awareness for the plights of people in Chinatown, particularly with regards to housing and healthcare issues.

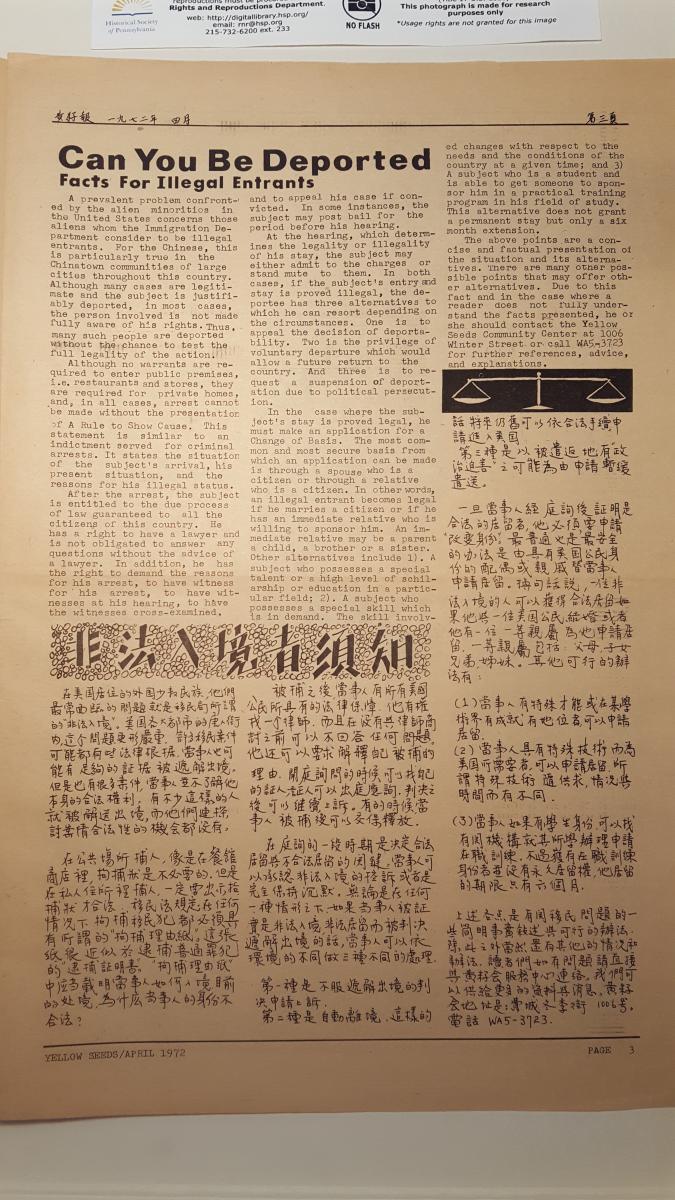

Contrary to the overall tone of its predecessor, however, Yellow Seeds serves less as an appeal to the compassion of the religious as it does as a rallying call for unity against injustices facing the Chinese American community. This is reflected in its contents, with article titles ranging from “What Does Chinatown Mean to Me?” and “Suzy Wong/Charlie Chan: Is that really me?” to “US Policy in Vietnam: Why Should Asians in America Keep Well Informed About US Policy in Asia?,” “Can You Be Deported: Facts for Illegal Entrants,” and “Why Learn English?!”.

An article titled "Can You Be Deported: Facts for Illegal Entrants" that was published in the first issue of Yellow Seeds. The newspaper contains many articles targeting issues and concerns pertinent to the Chinese American population, including a list of health symtpoms which require medical attention.

Having observed this difference, I can’t help but wonder: What would have happened to Dr. Moy if he had published a passage such as this, drawn from an article in Yellow Seeds?

“In order to ‘succeed’ we have to ‘operate’ in the American system—accept its values, play its games. But we are never fully accepted into this system because of our ‘slanted eyes and yellow skin.’ We must live in segregated communities to feel we are “among friends”. So we retreat to our Chinatowns and Little Tokyos, to our homes where old traditions compete with American ways.”

Of course, the 1970s were vastly different than the late 1800s, and it’s quite clear that such acerbic words come from people with a very different voice in society than before. This is perhaps made even more evident by the fact that I was able to treat the current equivalent of The Advocate and Yellow Seeds as packing material. But at the same time, the experiences outlined from one era’s advocate to the next reminds us of what is still left to change.