As we continue to develop plans for the William Still Digital History Project, I couldn't help but notice that this week marks the 175th anniversary of a watershed moment in Philadelphia's antislavery movement: the dedication and subsequent destruction of Pennsylvania Hall.

If you're not familiar with the story, a group of local abolitionists in the 1830s had decided to build their own gathering place after struggling to find meeting places willing to host them. After much hard work, Pennsylvania Hall opened on May 14, 1838 at 6th Street near Race Street. Former president John Quincy Adams wrote for the dedication ceremony, “the Pennsylvania Hall Association have erected a large building . . . wherein liberty and equality of civil rights can be freely discussed, and the evils of slavery fearlessly portrayed.”

Alas, not everyone in the city agreed with this plan. A mob gathered soon after the hall opened, and after several days of unrest, the hall was burned to the ground.

Fortunately, the fire did not destroy antislavery sentiment in the city. In fact, scholars now point to the destruction of Pennsylvania Hall as a turning point, when the unpopular abolitionists began to garner new sympathies among the general public.

Which brings me back to our project.

By the time William Still began his "Journal C," in December 1852, only fourteen years had passed since the burning of Pennsylvania Hall. Philadelphians were far from unified in opposition to slavery, and Still put himself at great personal risk by keeping a written record of the fugitive slaves helped by Philadelphia's Vigilance Committee.

That's quite a legacy to try to honor with this digital project. As you may recall, we're working to create a new web resource that will weave together Still's "Journal C" and the book he published some twenty years later, The Underground Rail Road.

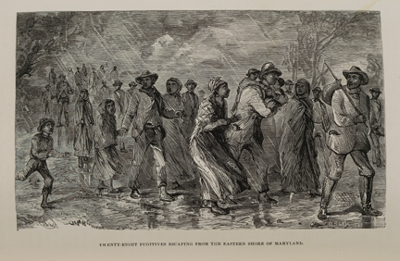

An illustration from Still's The Underground Rail Road. The caption reads, "Twenty-eight fugitives escaping from the Eastern Shore of Maryland."

As with our earlier digital history project, "Closed for Business," we'll be using XML text encoding, digital facsimiles of the documents, and additional annotation and contextual materials to help illuminate these important primary source materials. This time, we’ll also be testing out new mapping components to further explore the movements and network connections of the people profiled in Still's works.

Our first task, well before diving into the technical details of the project, has been to think about the stories captured within Still's writings. What do we want web users to take away from their interactions with these important documents? What theme or themes can we extract from his writings to help modern audiences better understand this difficult subject matter?

Based on feedback from our advisory committee, we decided to focus this initial prototype on the experiences of families escaping to freedom. This interpretive theme also supports Still’s original intent: that his records would help to reconnect families separated by the terrible institution of slavery.

Our contract researcher Peter Hinks helped us select three families profiled in Still’s works – the Shepherds, the Taylors, and the Wanzers – and we'll rely on their stories to explore a diverse range of fugitive experiences.

Longer term, we hope that the William Still Digital History Project will also help shed new light on the many people in Philadelphia and the surrounding region who helped to feed, house, clothe, and move fugitives through the area. We know from Still’s writings that these helpers included many average people, especially free blacks within Philadelphia and surrounding towns, but we look forward to finding new insights into this large network of support.

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this project do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.