As an intern for the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, I have been reading through the Albert M. Greenfield papers and researching the key figures connected with the Bankers Trust Company – a large Philadelphia-based bank associated with Greenfield which closed in December 1930. A couple of weeks ago, I came across some documents of Bryn Mawr College sent to Edna Greenfield (née Edna Florence Kraus), Albert’s wife from 1914 to 1935 and BMC alumna from the class of 1915. These artifacts provide a glimpse into the defunct Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers, which was of particular interest to me as an alumnus of Haverford College who will soon be marrying a Bryn Mawr graduate myself.

The Summer School program, established in 1921, emerged as an important opportunity for working women during an era of progressive reform in education, labor, and feminism. The school permitted female industrial workers to take classes at Bryn Mawr in a variety of liberal arts subjects, with required courses in economics and English and secondary courses in science, psychology, and history. Students accepted into the program were given a $250 scholarship and, in addition to the traditional courses offered in the classroom, they were also tutored in artistic and athletic activities as well.

The women who participated in the Summer School were 20-35 years old, came from different educational and social backgrounds, and they worked in a variety of industrial trades such as garment and textile production, millinery (hat-making), watch-making, and laundry. They comprised an ethnically diverse student body – nearly half of the 105 students in the 1929 Summer School session emigrated from European countries. The Summer School was also notable for its devotion to improving educational opportunities for African-American women. One of the Summer School’s founders, dean of the college Hilda Worthington Smith, was a passionate activist for integration who operated a similar educational program for black campus employees. In fact, the Summer School predated the college in integration, admitting its first black student during the summer session of 1926 before the college did the same one year later.

The guiding progressive mission of the Summer School was frequently at odds with that of its more conservative donors. Some women who took courses at the Summer School became actively involved in union organizing and took on greater roles in the labor rights movement. The 1935 session was canceled following a controversy when members of the faculty participated in a strike at Seabrook Farms the previous year, and in 1938, the Summer School was closed when, according to former student Sophie Schmidt Rodolfo, “the novelty wore thin and the money ran out.” The school and its mission became the subject of a short documentary in 1985 entitled “The Women of Summer.”

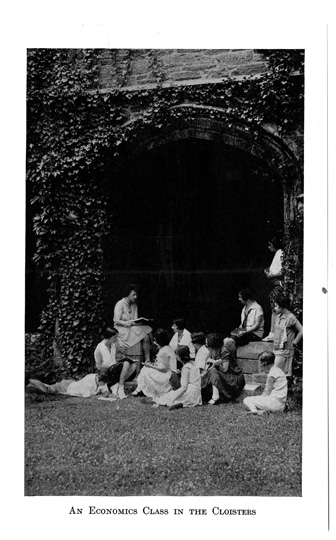

A letter written by Emily Read Cheston (BMC class of 1916) to Edna Greenfield in February 1930 gives a brief report on the 1929 Summer School session. Greenfield contributed an undisclosed amount to the program which benefited a diverse group of 23 students who worked in clothing factories and other industrial trades.

Letter from the Bryn Mawr Summer School to Edna Greenfield, February 6, 1930.

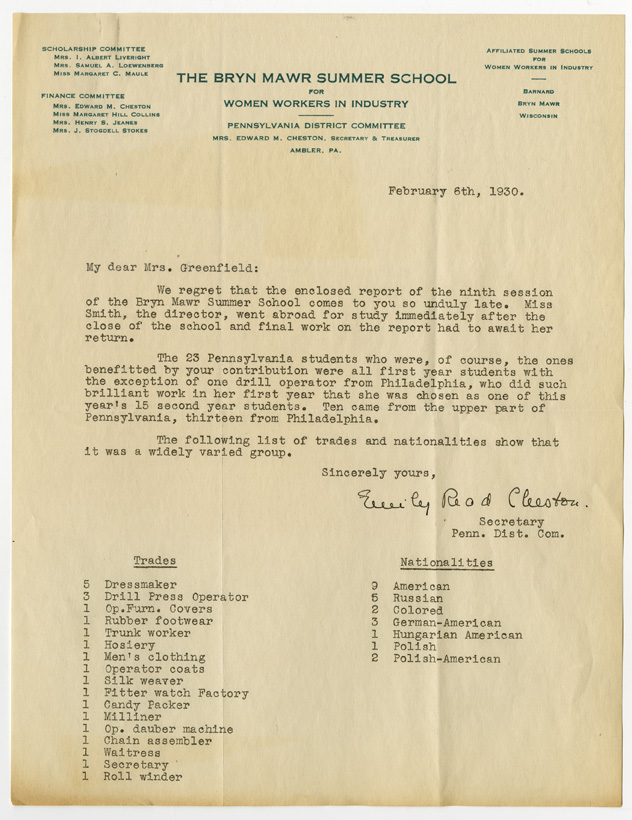

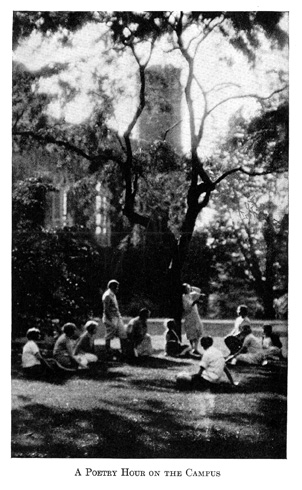

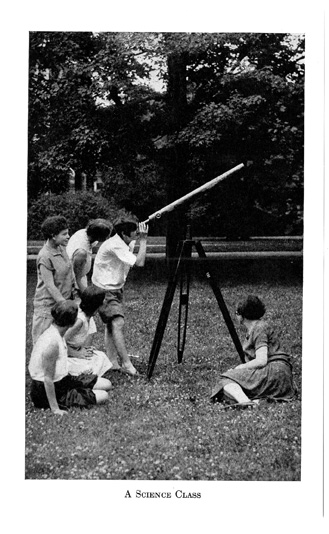

As part of its solicitation for donations, the Summer School sent Greenfield an informational leaflet about the program and enclosed some photographs of students participating in economics, science, and poetry courses.

Left: A poetry hour on the campus. Right: A science class.

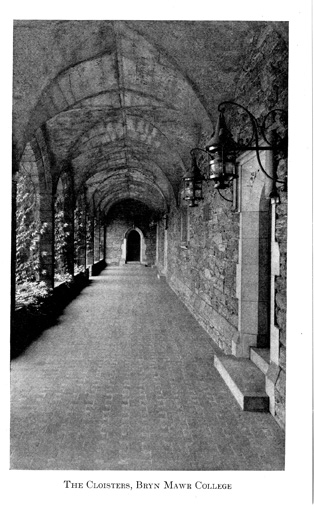

Left: An economics class in the Cloisters. Right: Another view of the Cloisters.

Observers will note that the students in the photographs are attending their classes not inside a classroom, but outdoors around Bryn Mawr’s scenic campus, an educational method that was likely not previously available to many of the women who worked for long hours inside factories and plants.

Despite its relatively short life, the Summer School had a significant educational impact on the lives of working women. As the former student Malvina Brooks wrote about its value in 1931: “We read, we study in the classroom, we express our opinions, and we discuss our industrial conditions. We are taught something about this universe. We learn that the world is not made up of just a mass of good and bad people. We find out that different conditions have made different classes of people, and that conditions can be changed. It is up to us, the working people, to change these conditions for a better world.”

For any current or former BMC students who happen to read this blog post, it would appear that the school was just as vibrant and intellectually stimulating – and the campus was just as beautiful – in 1929 as it is in 2012.

*************************************

You can see a copy of a 1915 Bryn Mawr College yearbook, including a photograph of the class of 1915 (Edna Greenfield’s class), at this link here.

*************************************

References:

1. The Albert M. Greenfield Papers, 1921-1969 (1959 Collection), Series 4: Edna Kraus Greenfield, Box 1030, Folder 4, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

2. Rita R. Heller, “The Women of Summer: The Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers, 1921-1938.”

3. Suzanne Bauman and Rita Heller, The Women of Summer: An Unknown Chapter of American Social History, review of a documentary by Mary Frederickson in The American Historical Review, Vol. 92 No. 1 (1987), p. 232-234.

4. Karyn Hollis, “Writing by Women Workers at the Bryn Mawr Summer School, 1922-38.”