by Jo Mikula, Haverford College Philly Partners Intern

Looking back on the refugee crisis that followed the Vietnam War, we searched our archives to get a closer look at the refugee experience. But what can historical documents tell us about the deeply personal experience of displacement? How far can photographs and official records go in helping us piece together events from the past, and where do they fall short?

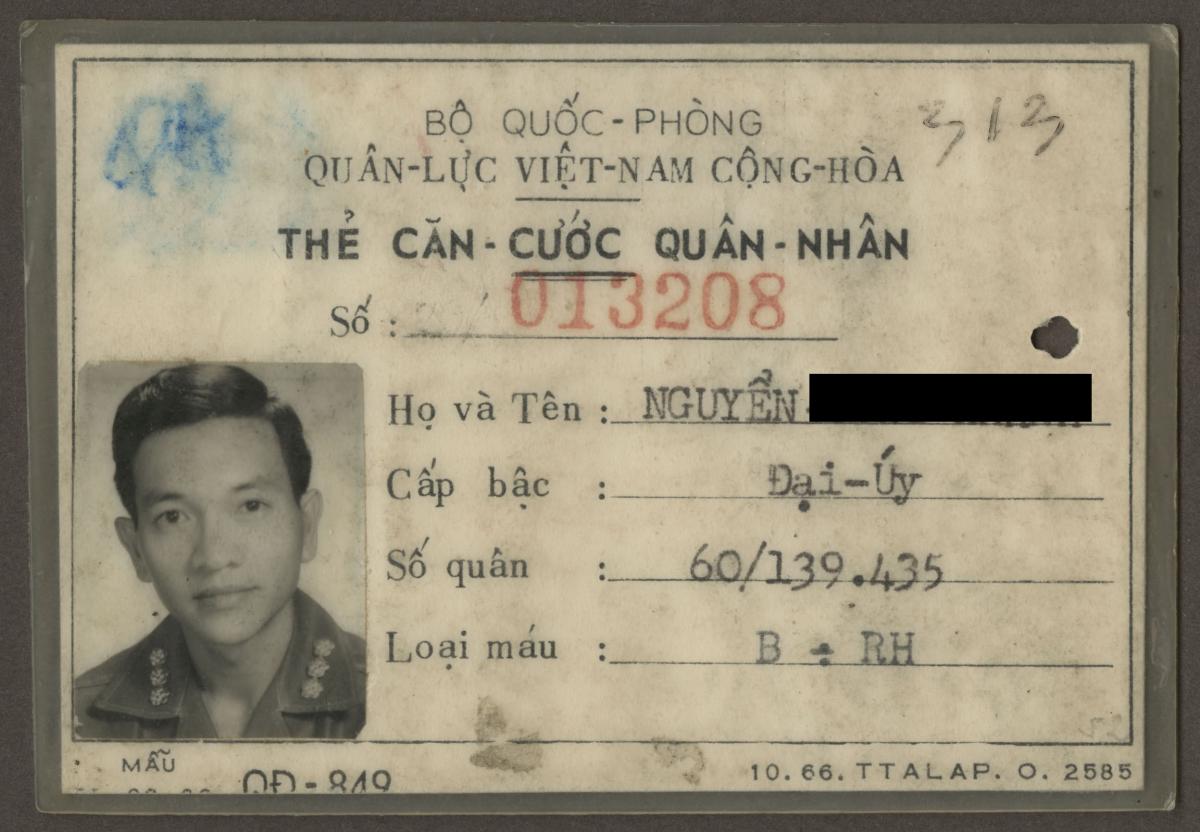

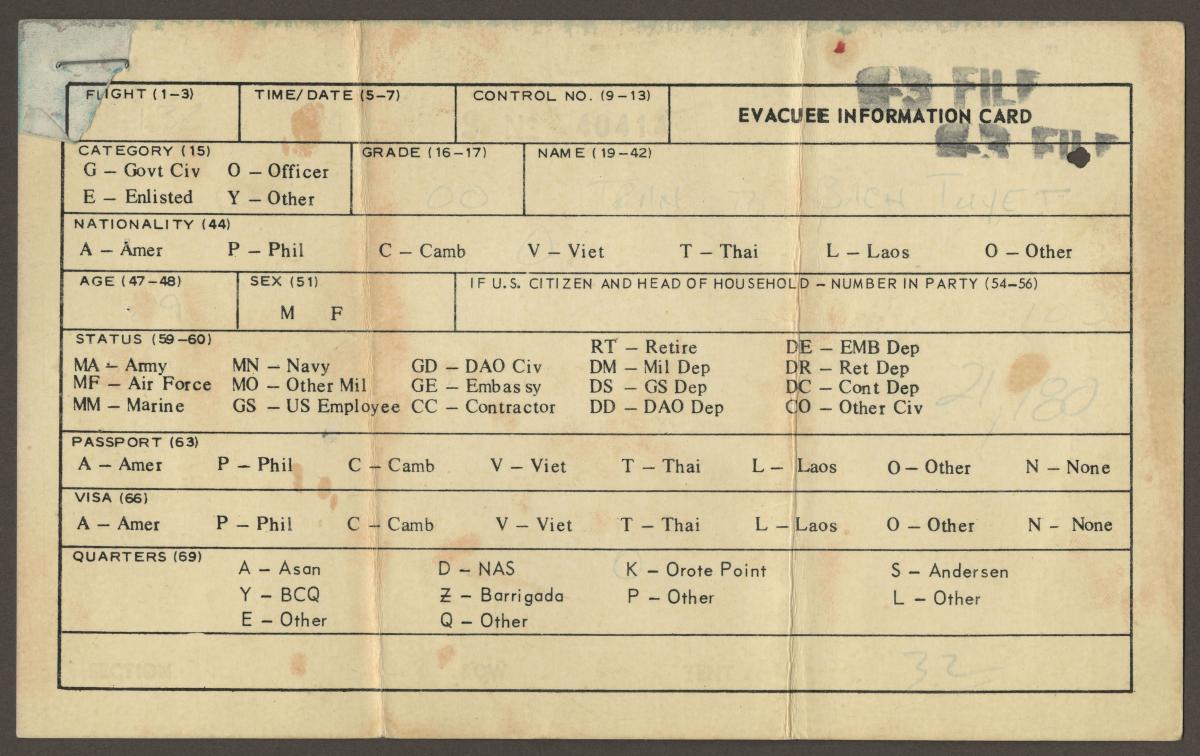

The Nguyen family was among the over 130,000 refugees to relocate to the United States following the Vietnam War. Initially from South Vietnam, they were evacuated from Saigon to Guam and then to a resettlement camp in Indiantown Gap, PA. HSP holds records of the family’s journey, including ID cards, evacuee information cards, medical screening record tags, and bank notes from before the Communist takeover of South Vietnam. The HSP collection also includes a number of Nguyen family photos taken in both Vietnam and in Indiantown Gap.

Personal evacuation records from Nguyen Family Collection

While these documents and photos provide insight into the process of relocation, they fail to express the emotional and mental state of Nguyen family members as they fled their home country and relocated to multiple temporary camps before finally settling in the United States. The fact that the Nguyens saved materials like evacuee information cards and South Vietnamese money seems to indicate a desire to document both their daily life from before the war and their journey. We cannot, however, presume the exact personal significance of these items, and no letters or diaries exist in HSP’s collection to relay their thoughts and feelings. In order to get some understanding of their individual experience through the HSP collection, we must turn to the Norman V. Lourie Papersmay h.

A collection of documents from Norman V. Lourie, a social worker and government employee who worked with Southeast Asian refugees, the Lourie papers include discussions of the struggles these immigrants experienced upon relocating to the United States. Compiled from the input of caseworkers and conversations with refugees, most of the documents in this collection are government reports relating to the psychological state of refugees. One report highlights feelings of isolation and alienation as well as the cultural shock refugees may have experienced upon encountering life in the United States. Specific examples from the list of psychological stressors include “disruption of traditional family roles, and family security,” “racism and discrimination as an easily ‘targeted’ minority,” “uncertainty of family reunification prospects,” and “economic necessity of adjusting to new work habits.”

While useful, the Lourie papers are bureaucratic interpretations of the refugee experience rather than personal refugee accounts. One document, a “Refugee Adjustments Time Table,” attempts to identify stages of assimilation, applying behavioral patterns and time frames to each stage. In Stage I, the refugee will experience “panic, shock, and survival traumas of initial exodus.” Stage V, which can happen anywhere from a couple months to a couple years after the initial exodus, is characterized by “hope emerging and new self-identity emerging.” At the very least, the time table obscures the complexity of the resettlement experience and the uniqueness of each experience. In many cases, it blatantly fails to acknowledge the effect that resettlement had on many refugees. The neat concepts of adjustment and re-birth stand in stark contrast to the words of one Vietnamese refugee who said: “I had so many hardships to bring my son to this country, and he said to me, my life is so hard right now, I wish I had never been born.”

Ultimately, HSP’s collection of government and medical documents pertaining to the Southeast Asian refugee crisis is a powerful reminder of the gap between institutional interpretation and individual experience. Voices and truths are obscured in the pages of government documents where the process of immigration is generalized in timetables for “adjustment” and “re-birth.” Personal narratives are an important counterpoint to the shortcomings of this broad institutional language, as evidenced by undertakings like VietStories , a Vietnamese American oral history project run through the University of California, Irvine, which documents personal refugee accounts in order to “change misconceptions” about Vietnamese refugees. HSP’s own Becoming US program has a similar goal, seeking to “personalize stories often presented in the media in only the broadest of strokes” through dialogue between people of different ethnicities and nationalities now living in Philadelphia.

This post is part of an ongoing series revisiting the events of 1968, fifty years later. A previous article explored the Tet Offensive and the chain of events it set in motion that eventually led to the end of the war and the resettlement of millions of Southeast Asians in the 70s and 80s.

References:

Lourie, Norman V. Norman V. Lourie Papers. Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Nguyen family. Nguyen Family Papers. Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Nguyen family. Nguyen Family Photographs. Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

VietStories. “Mission”. Available at: http://sites.uci.edu/vaohp/about/our-mission/