This piece originally appeared in Hidden City Philadelphia on January 22, 2019.

In October 2018, business leaders and residents of Philadelphia’s historic Italian Market publicly announced a plan to establish the area as a business improvement district (BID). The plan–which follows in the footsteps of a similar proposal in 2016 that ultimately failed–would levy a fee on neighborhood property owners in order to improve infrastructure, increase cleaning services, and counter the blight precipitated by vacant properties along South 9th Street and adjacent roads.

A spate of economic woes sparked the latest BID campaign, including the closure of several meat markets (including Fiorella’s-Sausage, the 114-year-old family-run shop) and a slight decrease in foot traffic over the past couple of years. These setbacks stand in contrast with recent neighborhood success stories like chef and immigrant rights activist Cristina Martinez, whose popular Italian Market-based restaurant South Philly Barbacoa was recently featured on two major cooking programs, Ugly Delicious and Chef’s Table.

By making a home for themselves and thriving in the area, recent immigrants continue a neighborhood legacy that stretches back to the 19th century.

Endemic poverty in Southern Italy and Sicily resulted in mass immigration at the turn of the 20th century, with upwards of four million Italians resettling in the United States in the hopes of securing a better life. Historically the home of Irish, Jewish, and German communities, what is now known as the Italian Market in Philadelphia’s Bella Vista neighborhood became a cultural hub for newly arrived Italian immigrants. The burgeoning Italian community repurposed the first floors of the area’s row homes as storefronts, retaining the other floors for family living quarters and boarding rooms.

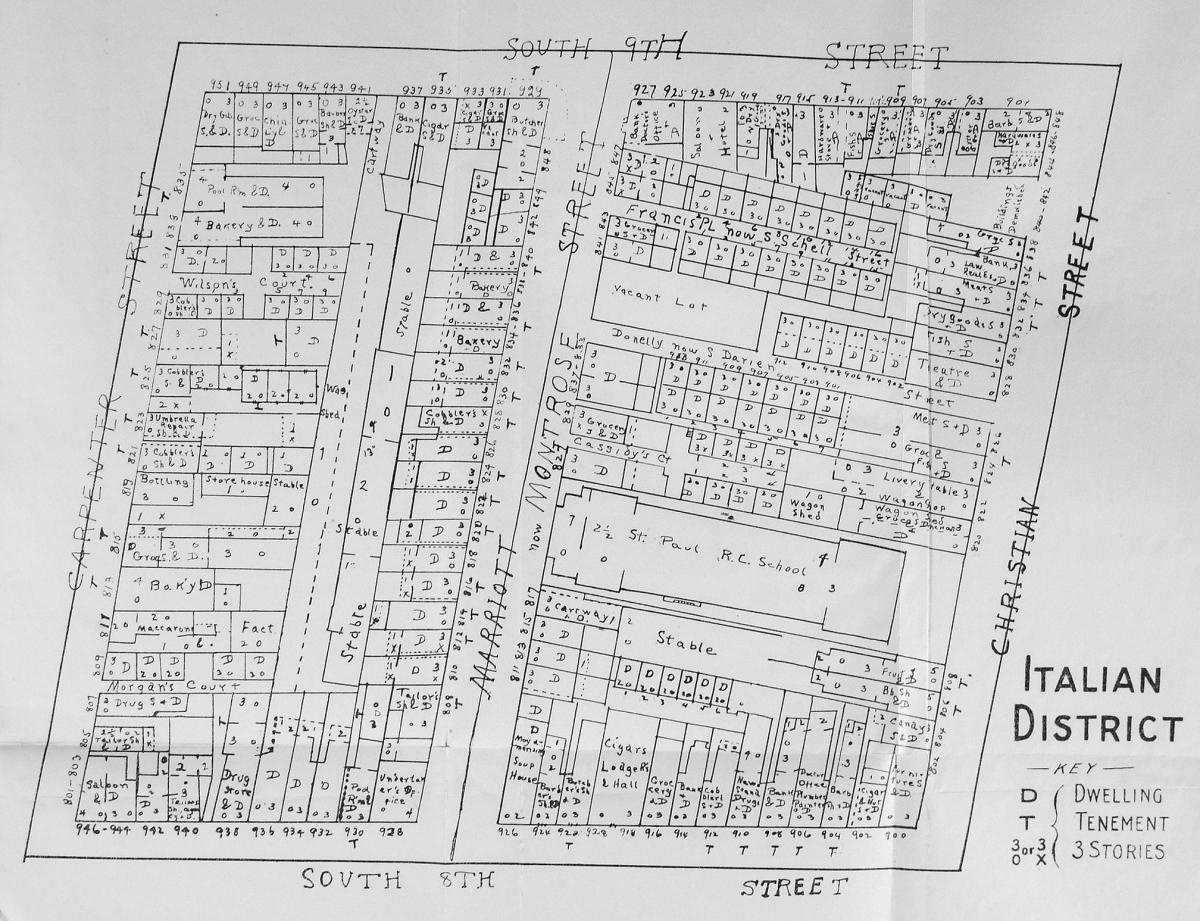

While the area provided economic opportunity to immigrants through the linguistic and cultural affinities of its blossoming Italian-American businesses, packed tenements and poor sanitary conditions underscored the dire economic conditions of the neighborhood’s immigrant residents, many of whom arrived in the United States penniless. A prominent housing advocate named Emily W. Dinwiddie mapped the neighborhood, then known as the Italian District, in 1904 to gain a clearer picture of its housing conditions. In her report, Dinwiddie noted that nearly 15 percent of families in the neighborhood shared a single toilet with six other families. “Health and decency are surely sacrificed under such conditions,”she wrote.

Map accompanying report by Emily W. Dinwiddie detailing building usage in the “Italian District.” The Octavia Hill Association commissioned Dinwiddie to investigate housing conditions in the neighborhood. Map. 1904. Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Over time, the neighborhood’s economy began to thrive, as second-generation residents enjoyed financial success and growing political clout. A group of business leaders established the South 9th Street Business Men’s Association in 1915, which organized to improve conditions in the area. Around this time, successful lobbying efforts resulted in city and state governments designating 9th Street as a curb market, thereby permitting merchants the right to sell their products out of pushcarts and stands along the sidewalk.

This distinctive commercial district gradually became known as the Italian Market by the middle of the 20th century. The neighborhood’s enduring significance as a center for the city’s Italian-American community and bastion of Italian culture is illustrated by an image from HSP’s archives that depicts the spontaneous celebrations on South Darien Street following the surrender of Italy in 1943 during World War II. Cheerful residents shared red wine and embraced on the sidewalk surrounded by U.S. flags.

As the 20th century progressed, many of the families who had called the Italian Market home for generations gradually moved away. While the Italian character of the area persists to this day, immigrants from countries including Mexico, Korea, and China have also established vibrant communities in the neighborhood, contributing their traditions to Philadelphia’s diverse cultural and culinary landscape.

Image from the Starr Centre Association’s 1909 annual report depicting the “Italian District.” The photo’s caption reads “Where Old Europe Meets New America.” Photograph. 1909. Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Image from the Starr Centre Association’s 1909 annual report. The photo’s caption reads “A Glimpse of the Italian District.” Photograph. 1909. Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Photo depicting Italian businesses along the 800 block of Christian Street. From left: Luigi Fiorella Meat Market (Fiorella’s Sausage), V. Di Pietro Watchmaker & Jeweler, and Genito Realty Company. Photograph. 1920. Fiorella Brothers Sausage Company Photographs. Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Interior of the Fiorella Sausage Company. Photograph. Circa 1920. Fiorella Brothers Sausage Company Photographs. Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Italian-Americans greeted the news of Italy’s surrender during World War II with an impromptu outdoor celebration on the 700 block on S. Darien Street. Wine flowed freely. Photograph. September, 1943. Philadelphia Record photograph morgue. Historical Society of Pennsylvania