During the American Civil War, political ideologies differed on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. There were Northern Copperheads who supported the Confederacy and thousands of Southerners who fought for the Federal forces. African Americans also were often divided in their sympathies or loyalties during the Civil War. Many sources attest that African Americans, both enslaved and free, either by force or by choice, served within scattered Confederate units as armed soldiers. Though laws existed within the Southern states prohibiting literacy or the use of firearms by enslaved people, such restrictions were not always rigorously enforced. Federal sources provide accounts of “full-blooded Negroes” doing picket duty or even serving as sharpshooters in the Confederate Army.

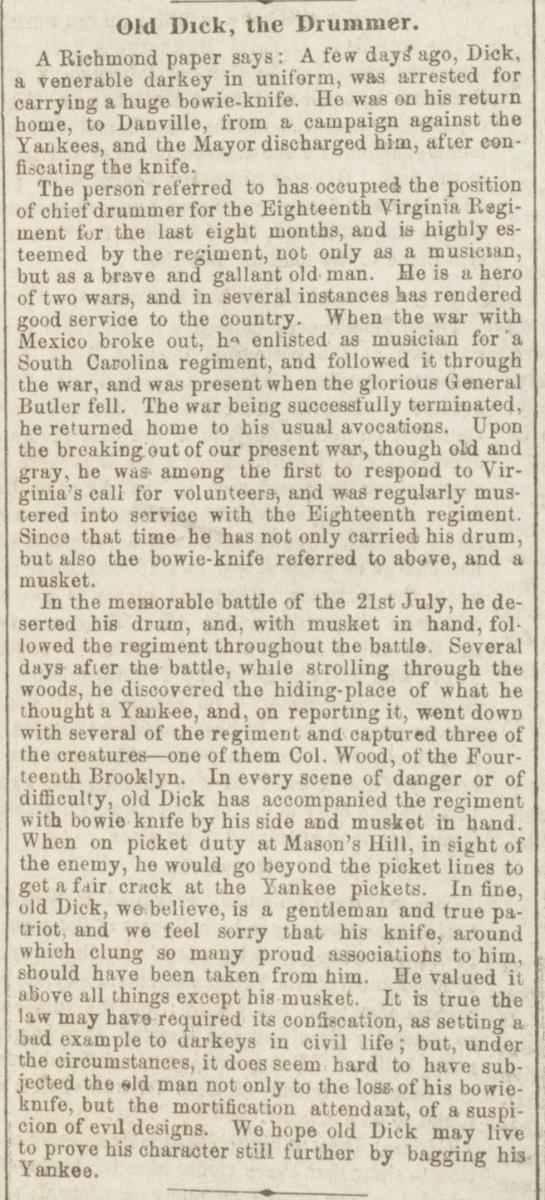

Perhaps one of the most famous accounts of an African American Confederate was that of “Old Dick the Drummer.” An account in Forney’s War Press on January 11, 1862, stated how this former Mexican-American War veteran “upon the breaking out of our present war … was among the first to respond to Virginia’s call for volunteers and was regularly mustered into service with the Eighteenth Regiment.” The article states that Dick was “highly esteemed by the regiment, not only as a musician, but as a brave and gallant old man.” Ironically, he was arrested for carrying a bowie-knife on his return home to Danville, Virginia, but had been carrying a drum, knife, as well as a musket.

Perhaps one of the most famous accounts of an African American Confederate was that of “Old Dick the Drummer.” An account in Forney’s War Press on January 11, 1862, stated how this former Mexican-American War veteran “upon the breaking out of our present war … was among the first to respond to Virginia’s call for volunteers and was regularly mustered into service with the Eighteenth Regiment.” The article states that Dick was “highly esteemed by the regiment, not only as a musician, but as a brave and gallant old man.” Ironically, he was arrested for carrying a bowie-knife on his return home to Danville, Virginia, but had been carrying a drum, knife, as well as a musket.

According to records at the National Archives, a man named Austin Dix, a “freed black; drummer,” served in Companies F and S from June of 1861 until his discharge from the Eighteenth Virginia Infantry, C.S.A., on August 31, 1863.

According to the article, during the First Battle of Bull Run in July of 1861, Dick “deserted his drum, and with musket in hand, followed the regiment throughout the battle. Several days after the battle, while strolling through the woods, he discovered the hiding place of what he thought a Yankee, and, on reporting it, went down with several of the regiment and captured three of the creatures—one of them Col. Wood, of the Fourteenth Brooklyn.”

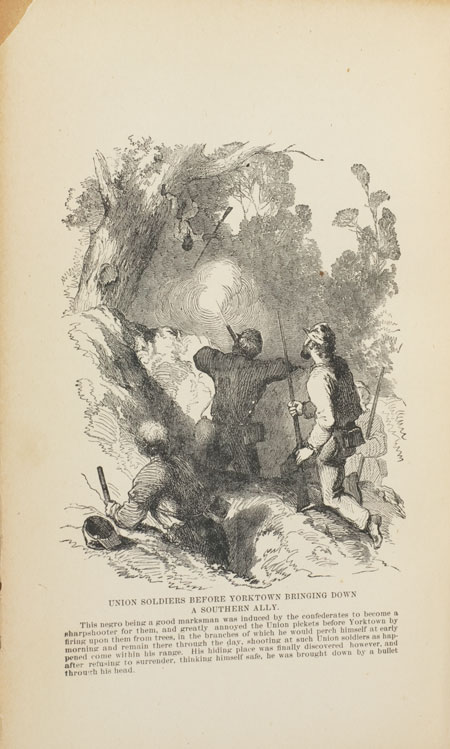

African American snipers or sharpshooters are mentioned frequently in Federal sources. Frazar Kirkland’s work Pictorial Book of Anecdotes and Incidents of the War of the Rebellion published in 1884 mentions “a rebel negro rifleman, who, through his skill as a marksman, had done more injury to our men than any dozen of his white compeers, in the attempted labor of trimming off the complement of Union sharp-shooters.”

African American snipers or sharpshooters are mentioned frequently in Federal sources. Frazar Kirkland’s work Pictorial Book of Anecdotes and Incidents of the War of the Rebellion published in 1884 mentions “a rebel negro rifleman, who, through his skill as a marksman, had done more injury to our men than any dozen of his white compeers, in the attempted labor of trimming off the complement of Union sharp-shooters.”

In a letter from HSP’s collections, dated August 18, 1862, Union soldier Abraham Kending mentions that on June 16, 1862, on James Island “in that fight there was eight negroes stationed behind an old chimney and they did pick off our men Savagely and no mistake, and no one can say but what they fought and stood their ground well, as there was but two of their numbers left to recount the doings of the day, the other six being killed dead on the spot.”

The above are only a few examples of numerous incidences where African Americans, either willingly or impressed to do so, fought in the defense of the Confederacy as armed participants. Such occurrences are what continue to make the history of the American Civil War so fascinating.