in conjunction with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and the School District of Philadelphia

[This lesson illustrates the variety of Digitized Educative Features that will accompany lesson designed for Reading Like a Historian 2.0. This Document-Based Lesson uses content from a lesson currently on hsp.org and does not necessarily incorporate all of the practices the new curriculum would. This lesson would be part of teacher discourse about how to teach "Crisis of the Union: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)."]

What arguments did abolitionists make against slavery? How did abolitionists propose to end slavery? These historical questions are at the center of this two-lesson unit focused on seven primary documents. In engaging with these questions and these documents, your students will consider the impacts and the limits of abolition, a social movement that spanned hundreds of years.

The documents in these lessons span from 1688 to 1860. To fully benefit from these lessons, students should be familiar with the basic history of slavery in the United States. Some understanding of colonial American history, the American Revolution, the era of Manifest Destiny, and the abolition movement will also be useful. In an American history course taught chronologically, these lessons would therefore fit best shortly before or shortly after covering the Civil War. In a history course taught thematically, these lessons would work well embedded in larger units on activism and social change or slavery and freedom.

In these lessons, your students will learn about the complex history of abolitionist thought in this country. They will develop their understanding by identifying and articulating the various arguments that people made against the institution of slavery and the different proposals made to try and end slavery. They will analyze documents to learn that anti-slavery ideas and emancipation plans changed over time, depending on their author, audience, and context. In the process, your students will develop historical thinking skills and learn historical concepts by answering the central historical questions with evidence from primary sources.

These primary sources will pose some challenges for students, not the least of which is their length. For this reason, you may choose to present students with the modified documents, also included in the lesson plans under "Other Materials." Note that the practice of adapting historical documents for the secondary classroom is supported by education research; for an introductory discussion, see “Tampering With History: Adapting Primary Sources for Struggling Readers” by Sam Wineburg and Daisy Martin, 2009. These lessons use an approach developed by the Stanford History Education Group. (See an intro to the model in this post on HSP’s Educators Blog.) They both consist of the following steps:

Building background knowledge

Posing a historical question

Analyzing primary sources

Answering the question in discussion or in writing, using the primary sources as evidence

The central historical question for this lesson on anti-slavery thought is: What arguments did abolitionists make against slavery?

The lesson is best taught over a series of class sessions, though it can be expanded or shortened as necessary. The key variable will be the amount of time spent on reading and analyzing documents. Teachers may choose to offer students modified versions of the documents, linked below under “Other Materials.”

Teaching the Teacher

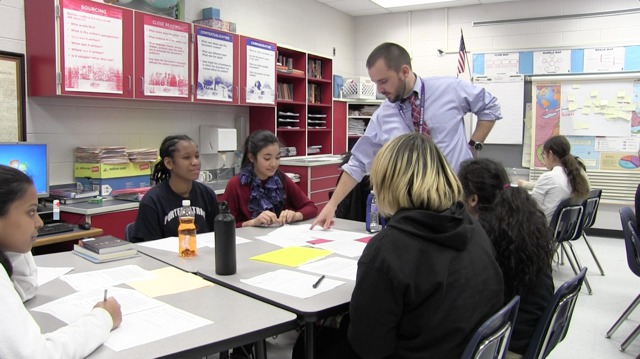

Coaching Video

[In the final product, this video would open onto a new page.]

Background Material for Teachers

UShistory.org, “American Anti-Slavery and Civil Rights Timeline”

David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World (2006)

Funder

Document-Based Lessons are a product of a grant from XXXX received by the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education and have been produced in partnership with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.