In 1961, US Supreme Court decisions that overturned racial segregation in interstate travel were largely ignored in the South. To challenge this status quo, more than 400 black and white Americans, called Freedom Riders, performed a simple act. They traveled into the segregated South in small interracial groups and sat where they pleased on interstate buses.

Organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the self-proclaimed "Freedom Riders" came from all strata of American society—black and white, young and old, male and female, Northern and Southern. They embarked on the Rides knowing the danger but firmly committed to the ideals of non-violent protest, aware that their actions could provoke a savage response but willing to put their lives on the line for the cause of justice.

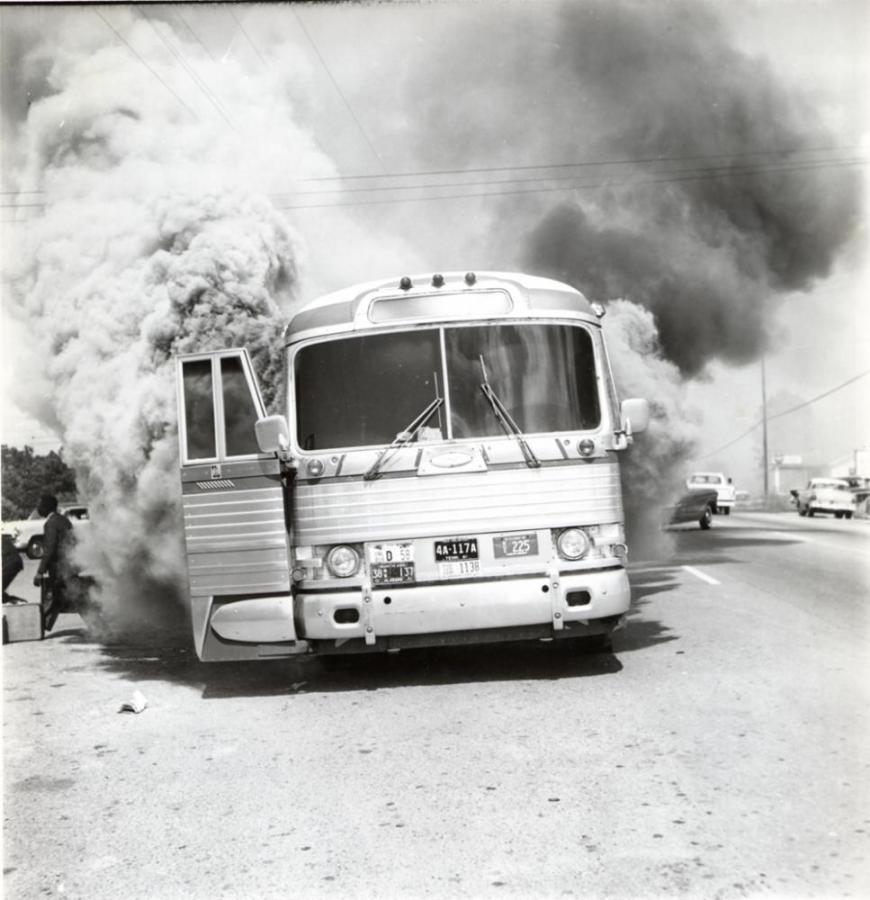

Mother’s Day, May 14, 1961: A Greyhound bus carrying the Freedom Riders was attacked by a mob who slashed its tires, and then firebombed the disabled vehicle outside of Anniston, Alabama. Photo credit: Birmingham Civil Rights Institute.

"It became clear that the civil rights leaders had to do something desperate, something dramatic to get Kennedy's attention. That was the idea behind the Freedom Rides—to dare the federal government to do what it was supposed to do, and see if their constitutional rights would be protected by the Kennedy administration," explains Raymond Arsenault whose book, Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, serves as the film's basis.

Each time the Freedom Rides met violence and the campaign seemed doomed, new ways were found to sustain and even expand the movement. After Klansmen in Alabama set fire to the original Freedom Ride bus, student activists from Nashville organized a ride of their own. "We were past fear. If we were going to die, we were gonna die, but we can't stop," recalls Rider Joan Trumpauer-Mulholland. "If one person falls, others take their place."

Later, Mississippi officials locked up more than 300 Riders in the notorious Parchman State Penitentiary.

Rather than weaken the Riders' resolve, the move only strengthened their determination. None of the obstacles placed in their path would weaken their commitment.

The Riders' journey was front-page news and the world was watching. After nearly five months of fighting, the federal government capitulated. On September 22, the Interstate Commerce Commission issued its order to end the segregation in bus and rail stations that had been in place for generations. "This was the first unambiguous victory in the long history of the Civil Rights Movement. It finally said, ‘We can do this.' And it raised expectations across the board for greater victories in the future," says Arsenault.

"The people that took a seat on these buses, that went to jail in Jackson, that went to Parchman, they were never the same. We had moments there to learn, to teach each other the way of nonviolence, the way of love, the way of peace. The Freedom Ride created an unbelievable sense: Yes, we will make it. Yes, we will survive. And that nothing, but nothing, was going to stop this movement," recalls Congressman John Lewis, one of the original Riders.

Finally, on September 22, the Freedom Riders triumphed. The Interstate Commerce Commission issued a sweeping desegregation order. As of November 1, Jim Crow signs had to be removed from bus stations. Every interstate bus had to display a certificate: “Seating aboard this vehicle is without regard to race, color, creed, or national origin, by order of the Interstate Commerce Commission.”

The Nashville Freedom Riders were led by students C. T. Vivian (left) and Diane Nash, center, who had organized other successful nonviolent protests in Tennessee. Photo credit: Tennessean.

The Freedom Rides led to further federal civil rights legislation and have become a model for grassroots movements to bring about social change.

Says filmmaker Stanley Nelson, "The lesson of the Freedom Rides is that great change can come from a few small steps taken by courageous people. And that sometimes to do any great thing, it's important that we step out alone."

The National Constitution Center invites you to a screening of Freedom Riders, exploring the terrifying, moving, and suspenseful story of these volunteers as they risked being jailed, beaten, or killed, as white local and state authorities ignored or encouraged violent attacks. The film includes previously unseen amateur 8mm footage of the burning bus on which some Freedom Riders were temporarily trapped, taken by a local twelve-year-old and held as evidence since 1961 by the FBI.

Jeffrey Rosen, NCC’s President & CEO and a constitutional law scholar, will discuss the heroic acts of the Freedom Riders and the conflicts with the Kennedy administration. Dr. Anthony Glasker and Dr. Charlene Mires, Associate professor at Rutgers-Camden and Director of MARCH (Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities), will join in the lively conversation about the 1961 Freedom Rides, and attendees will take a tour through the new Kennedy Exhibition.

For more information or to register, please contact Kerry Sautner at the National Constitution Center.

Signature image credit: Freedom Riders: Birmingham Civil Rights Institute/Mississippi Department of Archives & History

Created Equal: America’s Civil Rights Struggle is made possible through a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, as part of its Bridging Cultures initiative, in partnership with the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.