My work at HSP revolves around our manuscript collections, whether I'm processing, accessioning, researching, or paging. And I've dealt with many collections over the past several years of all shapes, sizes, and conditions. Because this work has become somewhat rote for me, and because so many collections regularly cross my desk, it's easy for me to overlook the unique facets of each. Our collections, known or unknown, each have human histories and carry along with them aspects of their creators. Two adopt-a-collections that I recently processed re-ignited the sense of specialness that our collections hold, even when they are not from the famous or known.

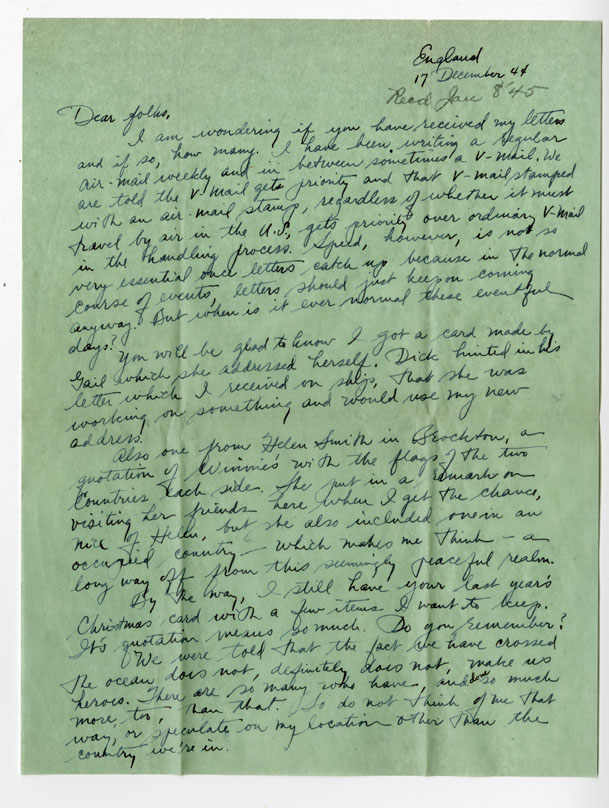

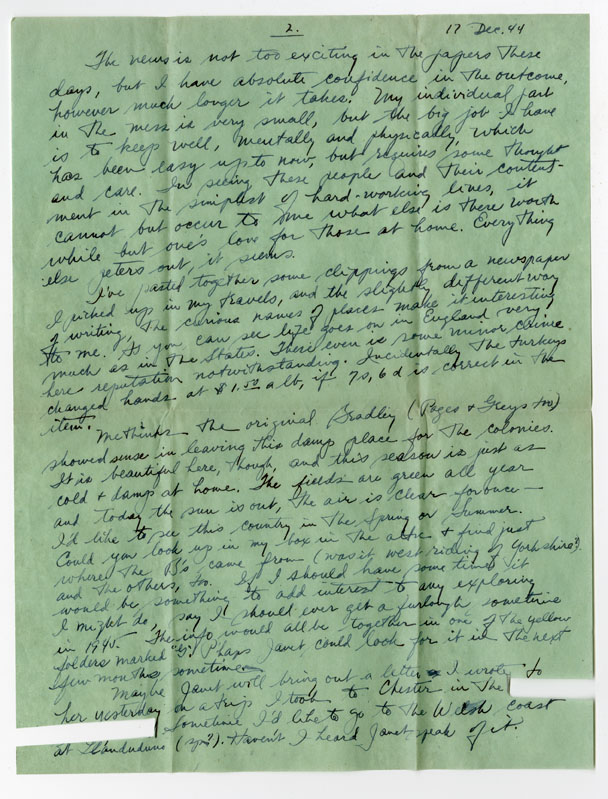

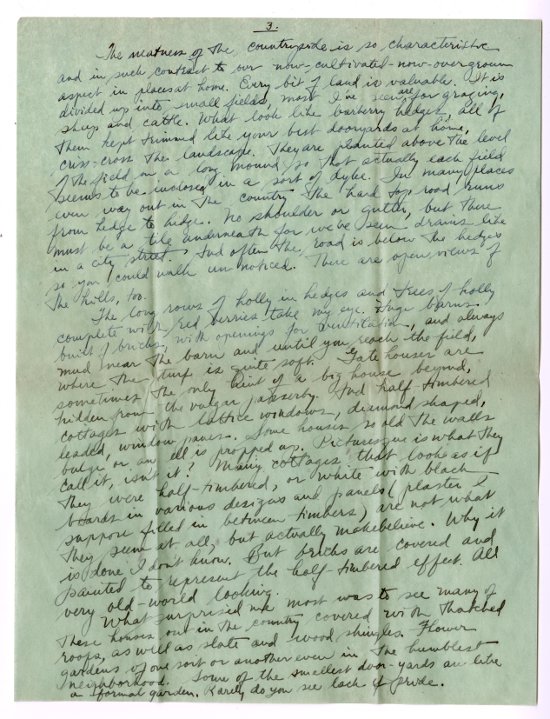

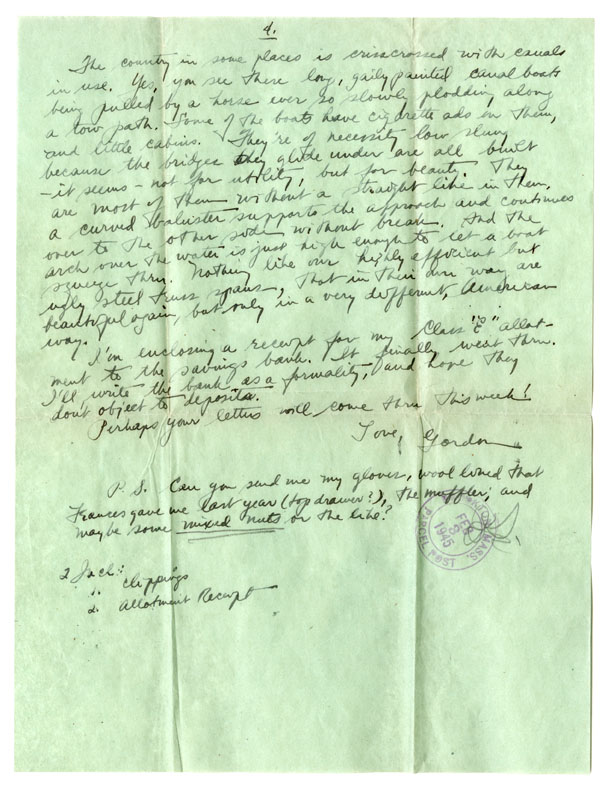

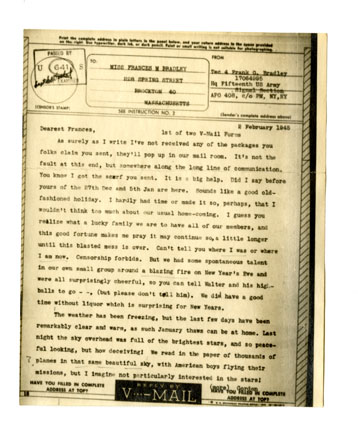

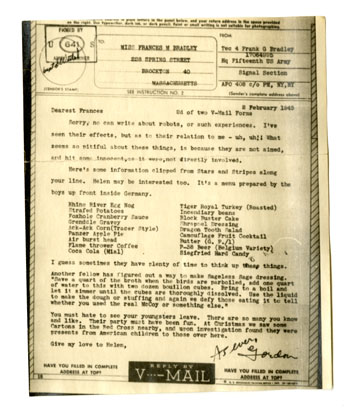

The Frank Gordon Bradley World War II correspondence (Collection 3548) came to us in 2010 and was adopted in 2011. In one small box were several hundred letters and v-mail from Bradley to his family, most still in their original envelopes, that had been carefully bundled according to Bradley's station. Bradley was born in Connecticut, enlisted in the army at Fort Riley, Kansas, in 1942, and moved to Philadelphia after the war where he worked as a librarian. These letters offer a fairly complete view of Bradley's service from its beginning in 1942 to its end in late 1945. During that time he was stationed at a variety of U. S. bases and was eventually sent to Europe in late 1944.

Even though Bradley could not discuss the details of his work, his letters are far from boring. After reading through many of them, I got the sense that Bradley was happy with this choice to join the army but that he missed his family. He rarely mentioned major war events (in one letter he remarked that folks at home probably got news faster than he did) but some letters are markedly more anxious than others. Once he started writing from Europe, though he couldn’t mention his exact location, he painted vivid pictures of his surroundings, friends, and foes.

The Bradley letters are immensely human and are a remarkably rich archive of one man's experience during World War II that no doubt shed light on the incidents encounters by some but not all soldiers during that time.

A far cry from the simplicity of a chronological set of letters, the Brake and Wineman families papers (Collection 3606), which was adopted just this year, represents well the personalities that are sometimes found in collections of family papers. This small but vivid collection documents the industrious and agricultural lives of the Brake family and the Wineman family, both from central Pennsylvania. Covering most of the nineteenth century, this collection contains a nice assortment of various kinds of materials from the families, such as deeds, correspondence, volumes, photographs, and clippings. Neither the Brakes nor the Winemans were particularly "famous," but one family member, Solomon Brake, was an early adoptedrof electricity and owned a mid-nineteenth century farm that was fully lit with the help of an onsite power plant. The Civil War touched the lives of at least the Winemans – Private George Wineman (1840-1863) served in the Union Army and died at the Battle of Gettysburg.

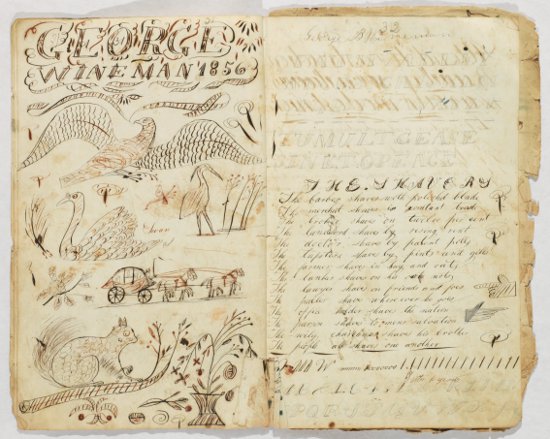

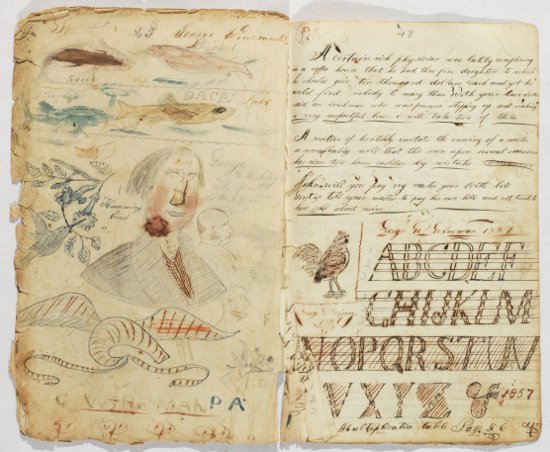

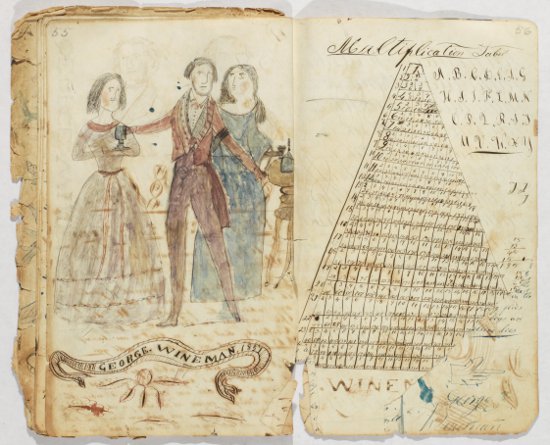

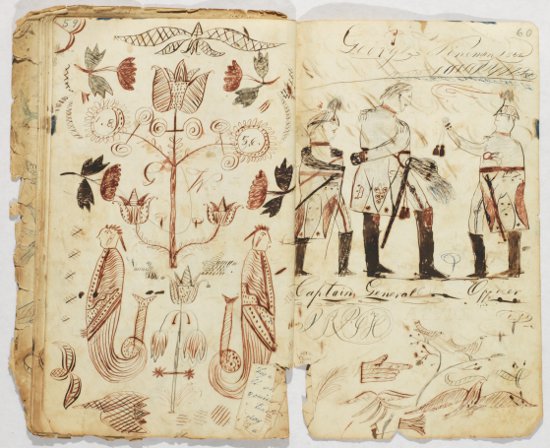

The Brake and Wineman papers is full of the things that would document any family and its contributions to its community; but it is the more private items, such as the collection's copy cooks, that highlight specific family member's personalities. There are four in the collection, and the one from the same George Wineman who fought and died during the Civil War, contains fantastic hand-drawn people, animals, and scenes.

This book dates from 1856 when George would have been around 16 years old. Encompassing the drawings are writings, problems, and exercises; but the number of drawings compared to the rest of the material in the book suggests that George may have been more interested in art than his studies. The fact that his life was cut short by the war compels one to consider just what he might have become if he had lived. An artist? A biologist? A designer? A farmer? While we can only speculate on an alternate reality for George, his book offers a clear window to his personality.

(A link to the Brake and Wineman families papers will be provided once the finding aid is ready.)

HSP's collections carry names big and small. While it's true that we have plenty of collections from elite families, mayors and governors, and famous organizations, we also have many more collections from folks who were only known in their backyards but served their purposes nonetheless. Whether farmer or artist, grocer or writer, these people from the background of history compelled it forward and serve as constant reminders of the humanity that is contained within manuscript collections.