Philadelphia is a city of firsts, including both the first brick house and pianoforte built in the United States, as well as the first published treatise against slavery. So it shouldn't surprise anyone that Philadelphia was also home to the first chartered, national bank. The Bank of North America was initially founded by the Second Continental Congress in 1781 to help fund the expensive Revolutionary War, which was badly in need of money and supplies. The BNA's records are on deposit at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and part of a massive conservation project which includes years of careful cleaning, mending, rebinding, and rehousing. These records span from 1723 through the 1920s and contain both what you'd expect from bank records (ledgers, cash books, day books, etc.) and a few surprises (wait until you see the poetry, the horse, and the hanged man, all coming in a later blog post).

The items in this collection came to HSP in 1939, deposited by the Pennsylvania Company, which at that point in time was the operating descendant of the Bank of North America. The collection has had varying levels of accessibility since then, with the condition of both the materials and the inventory limiting access for researchers. The first limiting factor is being addressed by the 3-year conservation project, which you can see photos of on HSP's revitalized Flickr page. (This page will be updated throughout the project so check back often or add it to your RSS reader.) As the project archivist, my job is to address the second factor that limited access -- the poor condition of the inventory -- by creating a new intellectual and physical arrangement so that researchers will have a better idea of what's in the collection.

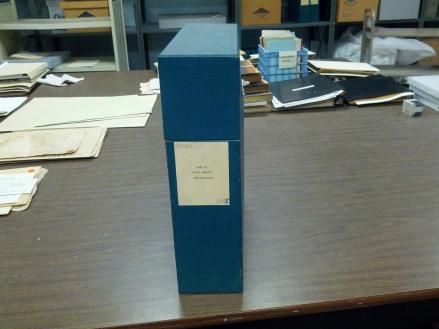

Improving access by creating a new physical arrangement means that all of the unbound materials (loose documents and artwork) in the collection need to come out of their old housing and into new folders and boxes. This is especially important because those green boxes aren't just old and unfashionable, they're...problematic for everyone who wants to access this collection. (But they were probably the height of archival science in the 30s, so we'll give past archivists a pass on this one.)

If you're researching in this collection, then a few different scenarios could greet you when you open one of those green boxes. The best case scenario for you and the collection materials is shown above: materials that are (believe it or not) in labeled folders, more or less kept flat by the folders and the way they're stored in the box. But you can't read the folder titles without removing the folders from the box, and you can't do that without turning the box on its side and dumping (well, carefully sliding) everything out onto the table.

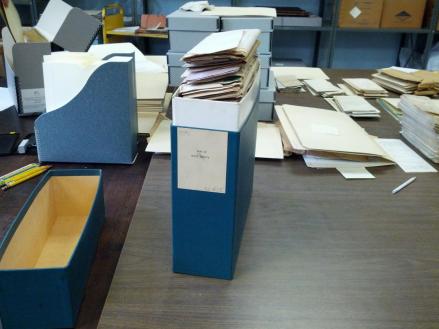

Your second best case scenario: sturdy, folded documents, not in folders, but not damaged either. The only way to get at these materials is by (again) dumping everything out and searching through a big pile of folded stuff that really doesn't want to be unfolded, one document at a time.

Here's your worst case scenario: unfoldered materials including very fragile newspaper, just rattling around in the box with no way to retrieve them without dumping everything out and pawing through it or shoving your hand in there and likely further damaging the materials. [Ok, actually I think a worst case scenario would involve organic materials, some bugs, and a humid storage environment, but thankfully this collection is free of most of those things.]

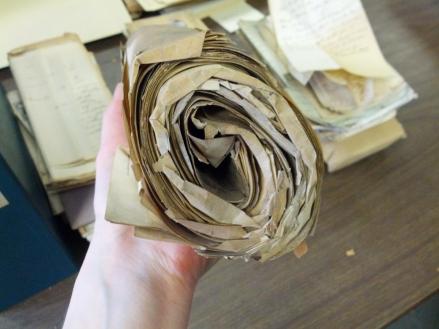

Underneath the crumbling newsprint was this:

It's a rolled mass of documents that can't, in their present state, be identified, dated, or read because a) the documents are too fragile to pry apart and b) they've been rolled for probably 70 years and would like to stay that way. But thanks to a little conservation lab magic, these documents have now been safely flattened and foldered and will soon be accessible for the first time.

The unbound portion of the collection is now comfortably resting in labeled, dated, acid free folders, inside acid-free document and photograph boxes. Each folder has a title and the contents are arranged in a way that will make it easier for researchers to find what they're looking for. As archival processing progresses, I'll be able to digitize a few items to show off on the blog and in our Digital Library, including Revolutionary War figures who banked at BNA, portraits of bank presidents, and of course the poetry, the horse, and the hanged man.