by Christina Larocco, Editor of Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography and Scholarly Programs Manager

“Welcome to the Miss America Cattle Auction!” read a sign on the Atlantic City boardwalk on September 7, 1968. One hundred members of the women’s liberation movement had gathered to protest the Miss America pageant, which seemed to represent everything the movement had risen up against: sexism, racism, jingoism, and consumerism. Singing and chanting as they marched, demonstrators threw into a Freedom Trash Can (but did not burn!) what they called “woman-garbage,” including “bras, girdles, curlers, false eyelashes, wigs, and representative issues of Cosmopolitan, Ladies’ Home Journal, Family Circle, etc.” A giant puppet with chains attached to her red, white, and blue swimsuit represented “the chains that tie us to these beauty standards against our will.”

First held in 1921, the Miss America pageant became a staple of Atlantic City’s post–Labor Day season.

“Trail-Breaking Beauties of Yesteryear”: Photograph of contestants at the first Miss America pageant in September 1921

Controversy characterized the pageant from the beginning. Formally segregated until 1950, the contest did not feature a Black finalist until twenty years later. The first (and only) Jewish winner, Bess Myerson, Miss America 1945, faced so much discrimination that she cut her tour short, devoting her time instead to the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith. Often called upon to boost troop morale, Miss America became a face of American foreign policy. By 1968, an unpopular war in Vietnam and a growing women’s movement—many members of which were also involved in antiwar and civil rights activism—made the contest a natural target.

“Bathing Beauties Visit Hospitalized Vets”: Miss America contestants visiting wounded World War II veterans in 1945

According to Carol Hanisch of New York Radical Women, the idea for the 1968 protest came out of a consciousness-raising session, conversations in which women shared their thoughts and feelings and came to realize that supposedly personal and individual experiences were actually social and structural. Historians give Hanisch credit for coining “the personal is political.” As Hanisch, Robin Morgan, and other women discussed the Miss America pageant, they developed a set of ten reasons for the protest. First and foremost, they rejected “the degrading Mindless-Boob-Girlie Symbol,” the dehumanizing process by which women were judged solely by their looks. They also criticized the pageant’s racism, its enthusiastic embrace of consumer capitalism, and its connections to US military involvement in Vietnam. “Last year,” demonstrators noted, “she [Miss America] went to Vietnam to pep-talk our husbands, sons, and boyfriends into dying and killing with a better spirit. . . . We refuse to be used as Mascots for Murder.”

Most onlookers and media commentators were not sympathetic to the protest. A small counterpicket of three people began, with more making their displeasure clear. “Go home and wash your bras!” shouted one man. The epithet “bra burner,” which antifeminists continue to use against women’s rights advocates, emerged from this protest. While no bras were burned, this event, which was the first widely covered media event of the women’s liberation movement, created powerful myths about the movement. Another man suggested that the protesters would be more useful if they threw themselves into a trash can. George S. Grimm of Rochester, New York, found the demonstrators un-American. “They shouldn’t have been allowed to march,” he fumed, “It’s an insult to our wonderful freedom.” Syndicated “humor” columnist Art Buchwald argued in the Washington Post that the beauty products protestors eschewed were necessary to curb domestic violence. “There is no better excuse for hitting a woman than the fact that she looks just like a man,” he wrote.

At the Ritz Carlton Hotel, just blocks away from Convention Hall, a different kind of protest was taking place: the first-ever Miss Black America pageant. According to Phillip H. Savage, tristate director of the NAACP, contest organizers hoped to counter the “false and hypocritical sense of racial awareness” that the older pageant fostered. Nineteen-year-old Philadelphia resident and Maryland State College student Saundra Williams, who planned to become a social worker, was crowned the winner, in part due to her visible commitment to both racial and gender equality. She criticized men who refused to take on an equal share of domestic labor, and she won the talent contest with the monologue “I Am Black.” Asked later if she would rather have won the Convention Hall pageant, she demurred. “I’d rather represent my race,” she said, “I think it’s important to show the country that black is also beautiful.”

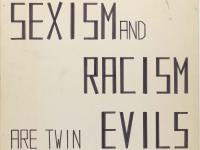

White feminists recognized in theory the intersections between race and gender. “Sexism and Racism Are Twin Evils of Society,” declared the Philadelphia chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW). But they often failed to implement this concept in practice. “Basically, we’re against all beauty pageants,” Robin Morgan said, “We deplore Miss Black America as much as Miss White America[,] but we understand the black issue involved.” The anger that Morgan and others felt toward beauty standards made it impossible for them to see how some women found beauty pageants empowering. Philadelphia Tribune journalist Marion Mosely, for example, was inspired by Miss Black America to envision greater possibilities for women.

The black press, which covered Miss Black America enthusiastically, found the mostly white women’s liberation protest silly at best, racist and appropriative at worst. The New Pittsburgh Courier implied that demonstrators were motivated primarily by envy, which certainly did not justify borrowing the spirituals that black Americans used to survive and protest Jim Crow. Miss Black America, proponents argued, was a “positive protest” meant to nurture racially inclusive beauty standards. “We’re not protesting against beauty,” J. Morris Anderson, one of the pageant organizers, said, “We’re protesting because the beauty of black women has been ignored.” From this perspective, protesting Miss Black America—which demonstrators conceded they were doing—was a racist rejection of black Americans’ right to claim beauty for themselves, or the idea that “black is beautiful.”

Focusing solely on the dichotomy between the women’s liberation protest and Black Miss America, however, risks obscuring the ways in which black women found themselves torn between a male-dominated civil rights movement and a white-dominated feminist movement. Bonnie Allen, who participated in the women’s liberation demonstration, wasn’t sure what to think about the competing protests. “I’m for beauty contests,” she told the New York Times, “But then again maybe I’m against them. I think black people have a right to protest.” But pitting these two demonstrations against each other also covers up the contributions black women made to both protests. Black lawyer and activist Florynce Kennedy was a key organizer of the women’s liberation protest. “I was the force of that,” she later said. On the day of the pageant, she chained herself to the puppet effigy and compared beauty standards to slavery. Thanks in large part to Kennedy, the women’s liberation protest borrowed many tactics from the civil rights and Black Power movements. Most histories of the protest, however, leave her out.

Intersectionality was, and continues to be, a weak point of many feminist movements. Historians and activists should not hesitate to challenge these blind spots when they see them. Yet scrubbing the record of activists like Kennedy to pit two protests against each other perpetuates this historical marginalization.

References:

“1st ‘Miss Black America’ Pageant to Be Staged in Atlantic City,” Chicago Daily Defender, Aug. 31, 1968.

Art Buchwald, “Uptight Dissenters Go Too Far in Burning Their Brassieres,” Washington Post, Sept. 12, 1968.

Bathing Beauties Visit Hospitalized Vets [electronic Resource]. 1945. Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Carol Hanisch, “What Can Be Learned: A Critique of the Miss America Protest,” Nov. 27, 1968, https://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/wlmpc_maddc01012/.

Charlotte Curtis, “Miss America Is Picketed by 100 Women,” New York Times, Sept. 8, 1968.

Enid Nemy and William McDonald, “Bess Myerson, New Yorker of Beauty, Wit, Service and Scandal, Dies at 90,” New York Times, Jan. 5, 2015.

Florynce Kennedy quoted in Georgia Paige Welch, “‘Up Against the Wall Miss America’: Women’s Liberation and Miss Black America in Atlantic City, 1968,” Feminist Formations 27, no. 2 (2015): 81.

Kreydatus, Beth, “Contesting Miss America: The Boardwalk Protests of 1968,” Pennsyvlania Legacies 18, no. 2 (fall 2018)

“‘Men Getting Awfully Lazy,’ Asserts Miss Black America,” Philadelphia Tribune, Sept. 10, 1968.

“Miss America Pageant Is Picketed by 100 Women.”

Marion G. Mosely, “Black Miss America Inspired Her,” Philadelphia Tribune, Sept. 17, 1968.

New York Radical Women, “No More Miss America!” Aug. 22, 1968, box 8, folder Culture, Rosalynn Baxandall and Linda Gordon Research Files on Women’s Liberation, TAM 210, Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University.

“Protestors Hit Miss America Pageant Goals,” Atlanta Constitution, Sept. 8, 1968.

“Women with Gripes Lured to Picket ‘Miss America,’” New Pittsburgh Courier, Sept. 21, 1968.