Part I. Dr. John Gibbon

In my work as an archival processor at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, nothing brings history to life quite like a family collection. The majority of collections that I have worked on in the past have consisted of institutional or organizational records: a mind-numbing mountain of board minutes, receipts, form letters, invoices, etc. that comprise most such 20th century collections and have contributed considerably to HSP’s own processing backlog. While these collections certainly have their research value, they don’t necessarily inspire one’s imagination. By comparison, processing and arranging the Gibbon family correspondence (Collection 3272) was a breath of fresh air. In fact, I felt a little sheepish throughout the whole thing because for a history lover like me, working on this collection felt like the thrill of discovery that accompanies digging through my own grandparent’s attic and people aren’t supposed to have that much fun at work.

The Gibbon family correspondence collection consists of letters originating from the family of Dr. John Heysham Gibbon, Sr. (1871-1956), a Philadelphia surgeon and professor at Jefferson Medical College. The collection features a large number of letters between Dr. Gibbon and his wife, Marjorie Young Gibbon. Based on the evidence of the letters, theirs was a very happy and close marriage and in fact they both died in 1956, only a week apart from each other. When they were separated, they wrote to each other about once a day (and sometimes more). Nowhere in the collection is their relationship better illustrated and their separation more poignant than the series of letters dating from May 1917 through December 1918, when Dr. Gibbon served with the Pennsylvania Hospital Unit in France during World War I.

Dr. John H.Gibbon, Sr. (center) and two companions while stationed in France.

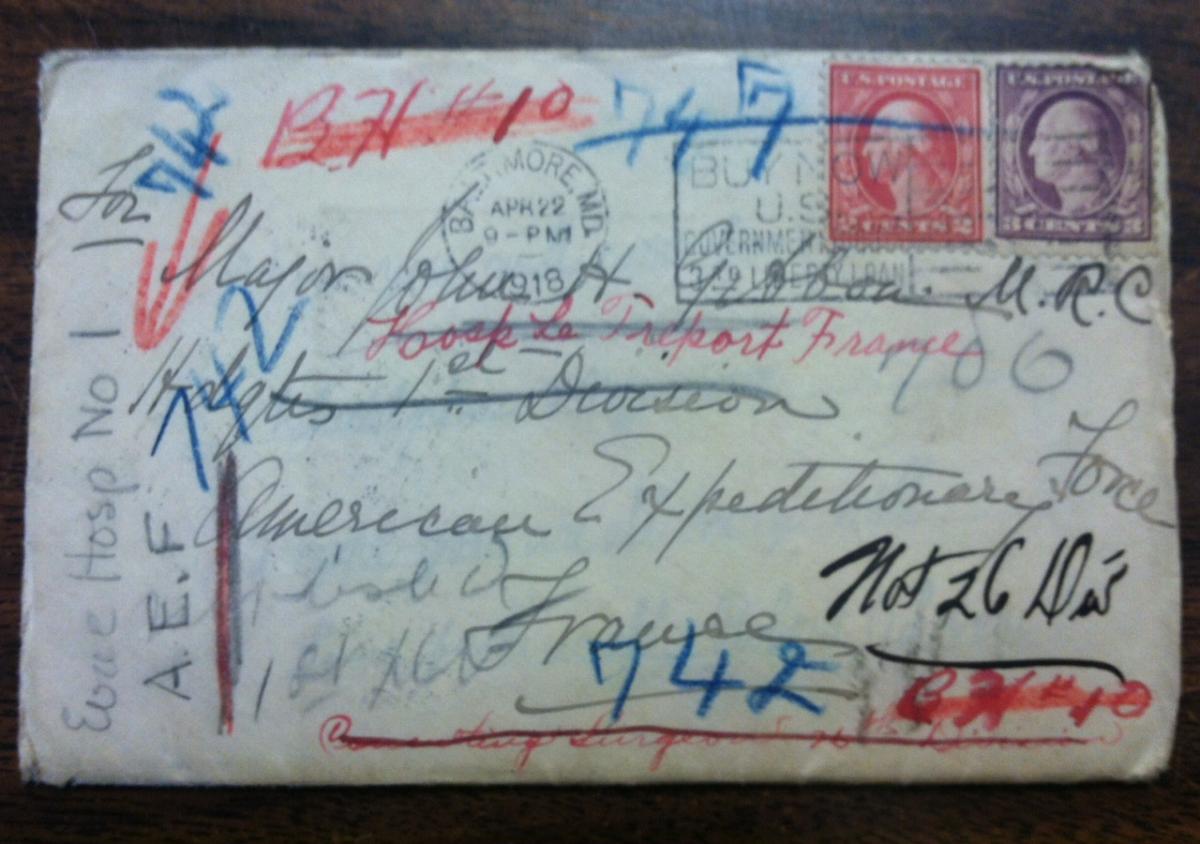

With the one hundredth anniversary of World War I occurring almost a year ago, HSP has seen increased interest in our collections pertaining to that time period. As such, it was determined that the Gibbon family collection comprises an important piece of those holdings. However, the collection was virtually inaccessible and unusable to our researchers since the letters were not arranged and stacked in boxes still in their original envelopes.

A sample envelope from the Gibbon family correspondence

And that’s where I came in. My job as processor was to remove the letters from their envelopes, unfold them, and try to wrangle some kind of meaningful arrangement from them so researchers might actually be able to use them. Opening each envelope was like unwrapping a Christmas present as I got to know and love the Gibbons though their letters, learning their nicknames for one another and their individual hopes, fears, and idiosyncrasies. Some envelopes even contained surprising little gems like photographs, postcards, pressed flowers, pencil drawings, and other pieces of ephemera. These treasures coupled with the personal nature and completeness of the letters vividly brings to life the family’s experience of World War I.

The Gibbon family, taken shortly before Dr. Gibbon left for France: (left to right) Samuel B. M. Young (Marjorie Young Gibbon's father), Robert Gibbon, Marjorie Gibbon, Marjorie Young Gibbon, Dr. John Gibbon, and Samuel Gibbon (John Gibbon, Jr. was the photographer for this shot)

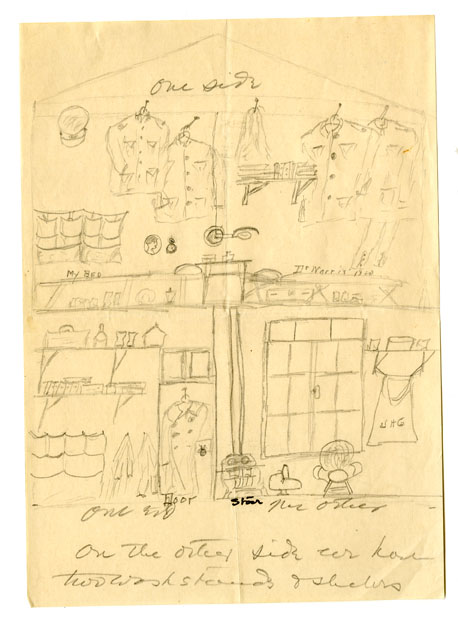

Dr. Gibbon left Philadelphia for France in May 1917 aboard the USMS St. Paul with a medical unit from Pennsylvania Hospital. He and his wife Marjorie were both forty-six and had four children: Marjorie aged 15, John Jr. or “Jack” aged 14, Samuel or “Sammy” aged 12, and Robert or “Bobs” aged 9. Their correspondence began almost from the moment of departure, with Marjorie and the children sending along farewell letters for Dr. Gibbon to open while onboard ship. After a brief stay in England, the hospital unit arrived at what was to be their home for the next sixteen months, Base Hospital Number 10 at Le Tréport in northeastern France. The hospital was a temporary structure of huts and tents constructed on the high white cliffs or falaises above the town, which had been built by the British Army near the beginning of the war. Life at the hospital was rustic but relatively comfortable with the staff usually housed two or three to a tent where they slept on cots and shared a small stove.

Dr. Gibbon's pencil drawing of his living quarters at Le Tréport, sent to his young son, Robert

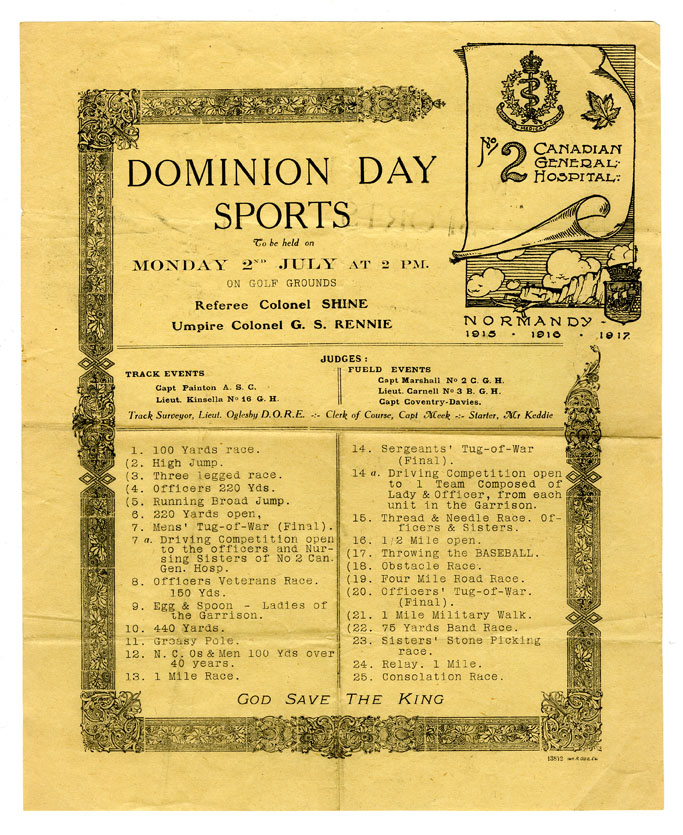

When the unit arrived at the end of June 1917, the hospital was overcrowded for its 2, 232 beds and would remain so throughout the summer months when fighting was at its peak. Work at the hospital could be grueling and exhausting with the surgical team required to work in twelve hour shifts at a time. But life at Le Tréport was not all grim. In an effort to keep up morale, the hospital organized its own band and several theatrical productions including a minstrel show. Holidays were still celebrated with as much festivity as could be mustered and were shared with Canadian and British units stationed nearby.

Dr. Gibbon attended the Dominion Day festivities of the nearby Canadian General Hospital No.2

Three months into his service, in October 1917, Dr. Gibbon was selected as part of a surgical team to relieve those who had been stationed at Casualty Clearing Station Number 61 since June. These Stations (abbreviated C.C.S.) were military medical facilities located immediately behind the front lines of battle. As such, they administered the first stage of treatment that wounded soldiers received after field dressing on the battlefield. Dr. Gibbon described his arrival in an article written after the war:

“The country was flat and the mud was ankle deep except on the macadam roads. The hospital was composed of a few Nissen huts and many tents. Creature comforts were notably absent and the environment was depressing. After dinner in the mess tent we paid a visit to the Nissen hut, which was known as ‘the operating theater,’ and which contained five operating teams at work with the floor covered with wounded men on stretchers awaiting their turn for an operating table. This view gave me for the first time in my life an impression of what the layman’s idea of surgery is. Never before had surgery seemed so unattractive to me.”

C.C.S. No. 61 was also the scene of frequent enemy bombings, which both frightened and frustrated the medical team:

“No. 61 was one of those unfortunate hospitals which was frequently the scene of the most distressing sight which human eye can witness, that is the re-wounding and killing of already wounded men by an enemy’s bomb dropped suddenly in the dead of night. There was hardly a moonlight night that the Hun did not visit our neighborhood and drop bombs, but only on one occasion during our stay was our hospital hit. Six patients and an orderly were killed. Two of the patients were Germans and all had been operated upon a few hours before. During the last few weeks of our stay, Newlin [another doctor] and I slept below the level of the ground in shallow graves, two by six feet by eighteen inches deep, which were dug through the floor of our tents, and when the anti-aircraft guns were shooting and particles of the exploded shells were falling, we partly closed over us a section of the floor of the tent which was hinged and which had a piece of sheet iron nailed on the underside. This does not sound like very comfortable sleeping quarters, but as a matter of fact it was much warmer and much safer than the floor of a tent.”

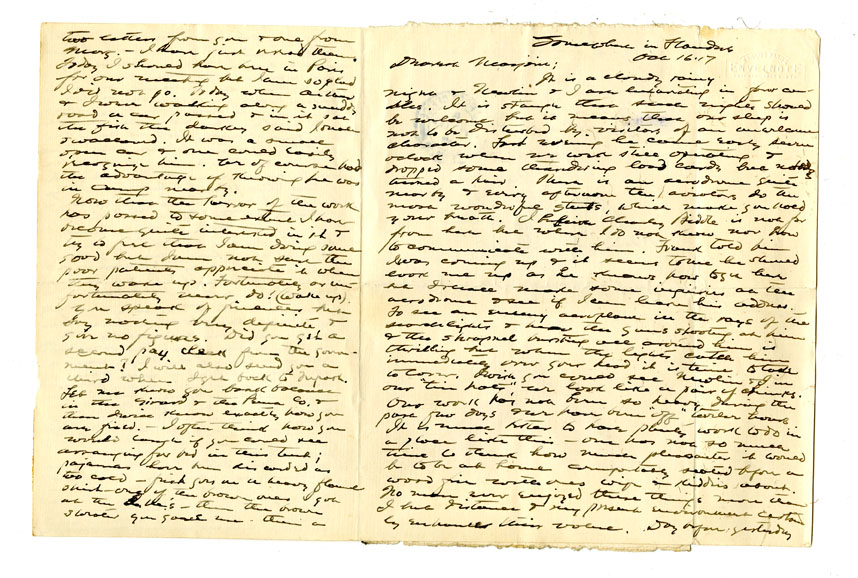

In letters to Marjorie, he was a bit less graphic and tried his best to maintain an upbeat and cheerful tone:

“To see an enemy aeroplane in the rays of the searchlight and hear the guns shooting at him and the shrapnel bursting all around him is thrilling but when the lights catch him immediately over head it is time to take to cover. I wish you could see Newlin and I in our ‘tin hats,’ we look like a pair of chinks! […] It is much better to have plenty work to do in a place like this –one has not so much time to think how much pleasanter it would be to be at home comfortably seated before a wood fire with one’s wife and kiddies about. […] Now that the horror of the work has passed to some extent, I have become quite interested in it and try to feel that I am doing some good but I am not sure the poor patients appreciate it when they wake up. Fortunately or unfortunately most do! (Wake up)”

Dr. Gibbon's letter to his wife Marjorie, October 16, 1917

It is telling of his experiences at C.C.S. No. 61 that Dr. Gibbon frequently reminded his wife not to expect too many letters while he was stationed there, since he had little free time and the environment was “not conducive to reading and writing.” By December 5, his surgical team had been relieved by a new one and was sent back to Le Tréport. He was even able to travel to Paris for the New Year, where he reported being able to take his first full bath in six months.

Dr. Gibbon's Christmas card sent to his family from Casualty Clearing Staion No. 61 (December 5, 1917)

After the war, Dr. Gibbon re-visited the site of C.C.S. No. 61 and received a souvenir piece of burlap taken from its sandbag fortifications.

According to a note found in the same envelope as the scrap of burlap, Dr. Gibbon had lunch with a Dr. Tuffier while visiting Paris in October 1919. Perhaps this man is who gave him the souvenir.

In the spring of 1918, it seems that Dr. Gibbon had more free time and was able to fill more of a supervisory role at the hospital. He was also able to take French lessons and make several day excursions to cities near the hospital including Nancy and Compiegne while visiting other Allied medical facilities for training sessions. He even befriended the extended family of his French teacher, Lucie Colin, and spent some of his time visiting with them.

Colin family photograph, included in one of Dr. Gibbon's letters

If at times life at Le Tréport seemed comfortable and civilized compared to the brutality of the trenches and Casualty Clearing Stations, there were still daily reminders that this was a war zone. In a letter to his daughter dated April 15, 1918 and written in French, Dr. Gibbon recounts an aerial battle he witnessed near the hospital:

[my rough translation] “Several days ago the American pilots returned to this sector and we are very excited because during two days they have brought down three German airplanes. I saw them this morning near our hospital. One of them was burning [and crashed?] but neither pilot was killed. I have attached here a piece of the wing of one of them, a souvenir for you.”

Piece of a German airplane wing sent by Dr. Gibbon to his daughter, Marjorie

By September 1918, Dr. Gibbon had been promoted to Lieutenant Colonel and was transferred to the relative safety of the American Hospitals in London where he served as consulting surgeon. Near the end of October, it was clear that the Allies were winning the war and by November 9, Dr. Gibbon was able to confidently inform his wife that by the time his letter reached her, the fighting would be over.

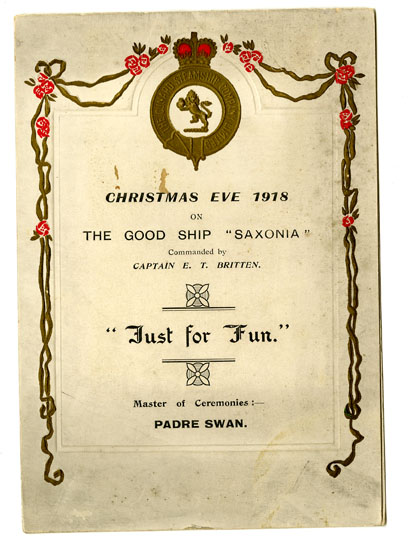

He was not, however, able to secure passage home until the second week in December and despite his wish to be with his family for Christmas, had to celebrate the holiday onboard the RMS Saxonia. The ship arrived in New York the next day where he was presumably greeted by an eagerly waiting Marjorie.

Christmas 1918 program for the RMS Saxonia

While the Gibbon family certainly did not suffer the worst privations of World War I and were lucky enough to emerge from it intact, their letters are nevertheless valuable for their incredibly rich documentation and brings this period of American history immediately to life.

Look for another blog post discussing Marjorie Young Gibbon’s experiences on the home front at a future date. In the mean time, check out the other World War I collections that HSP has to offer.

Other sources cited for this post:

Gibbon, John H. "Two Months at Casualty Station No. 61." In History of the Pennsylvania Hospital Unit (Base Hospital no. 10, U.S.A.) in the Great War edited by Paul B. Hoeber, 147-152. New York: 1921.