Part II: Marjorie Gibbon

For part one of this post which provides a background of the Gibbon family correspondence (Collection 3272) and discusses the World War I experiences of Dr. John Gibbon, click here.

While Dr. Gibbon was operating on wounded soldiers in northern France, his wife, Marjorie Young Gibbon, remained in Philadelphia with their four children. Marjorie was the daughter of Civil War veteran and friend of Theodore Roosevelt, General Samuel Baldwin Marks Young. As a child and young adult, she and her four sisters lived at many different military locations throughout the United States, following the various appointments of her father. It was while her father was stationed at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri during the Spanish-American War that she first met a young Army doctor, John Heysham Gibbon. The pair immediately began a lively and affectionate correspondence. When she married Dr. Gibbon in 1901, they settled in Philadelphia which was in all likelihood the first permanent home that Marjorie had known. As such, when Dr. Gibbon volunteered to serve as surgeon with the Pennsylvania Hospital Unit at the United States' entry into World War I, her experiences in her father’s household most likely prepared her for the long separation.

Like most women of her social status in the early twentieth century, Marjorie did not hold a career outside of the home but spent her time raising her four children and supervising their education in addition to managing the family’s two houses and domestic staff; one near Rittenhouse Square in Philadelphia and one at Lynfield Farm in Media, Pennsylvania. As the wife of a professor of surgery and a naturally outgoing person, she also maintained an active social calendar of visits, lunches, outings, and occasional parties with many of Philadelphia’s elite families of the day.

Marjorie Young Gibbon and her four children, circa 1919: (left to right) Robert, Samuel, Marjorie, Marjorie the younger, and John, Jr.

When Dr. Gibbon left for France in May 1917, they began what was to be the longest separation of their marriage. Marjorie and the children (Marjorie aged 15, John Jr. “Jack” aged 14, Samuel “Sammy” aged 12, and Robert “Bobs” aged 9 in 1917) were prolific correspondents, sending several letters per week. Throughout the war, one of the constant frustrations of their separation was the delays and inefficiencies of the mail system, with letters sometimes arriving up to six weeks after their posted date. When letters from France did arrive in Philadelphia, they were a source of excitement which was anxiously anticipated and often read aloud to one another. Letters written by the children reveal that Marjorie did not always share the entire content of Dr. Gibbon’s letters to her, especially where they were of a more personal nature between husband and wife or "love letters," according to Marjorie the younger. Some of Marjorie’s letters quite candidly reveal the closeness of their marriage and illustrate the pain of their separation:

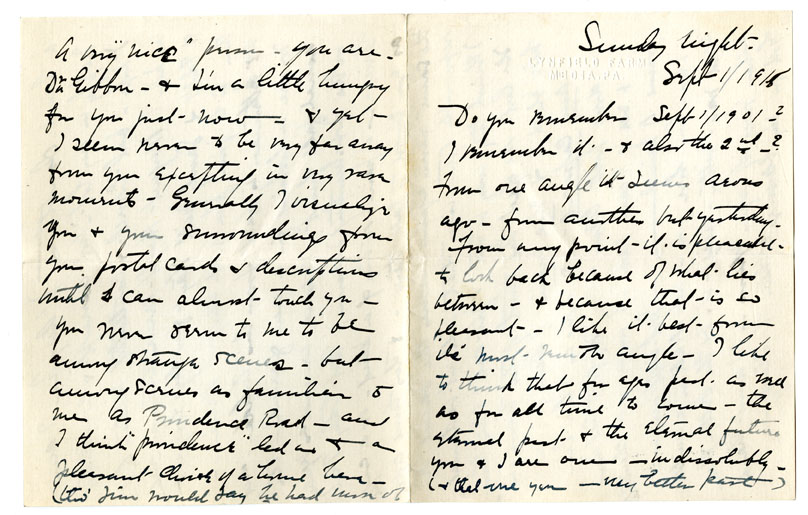

“Do you remember Sept. 1/1901? I remember it. And the 2nd? From one angle it seems aeons ago, from another but yesterday. From my point it is pleasant to look back because of what lies between[…] I like to think that for ages past as well as for all time to come--the starred past and the eternal future-- you and I are one--indissolubly (and that 'one' you--my better part). A very ‘nice’ person you are, Dr. Gibbon and I’m a little hungry for you just now and yet I seem never to be very far away from you excepting in very rare moments. Generally, I visualize you and your surroundings from your postal cards and descriptions until I can almost touch you. You never seem to me to be among strange scenes, but among scenes as familiar to me as Providence Road[…] ‘There is nothing between us but the sea!’ Did I tell you how I loved this little child’s thought, so wonderfully expounded, that you sent me a few days ago? There is more than a world dividing us from Germany. I feel like smashing all my German china on the hearth. What do you think I am doing to celebrate my wedding anniversary? […]”

Marjorie’s letters to Dr. Gibbon written on their wedding anniversary September 1, 1918.

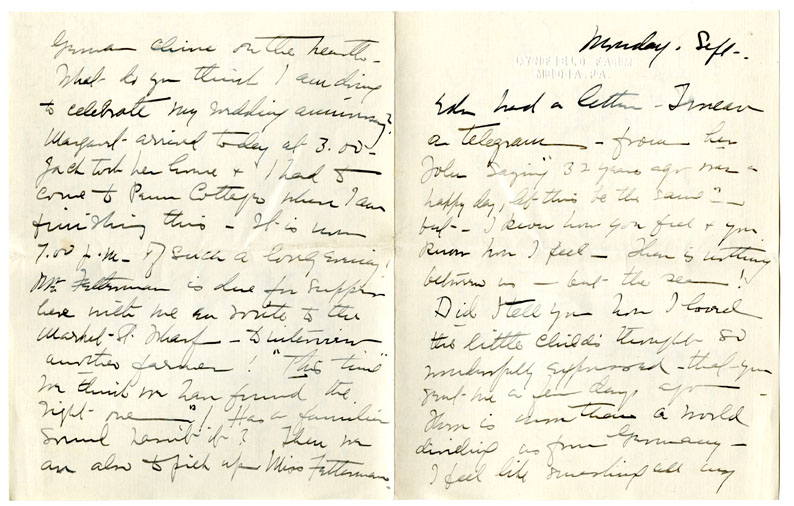

Yet Marjorie did not pine away idly. She volunteered much of her time with the Philadelphia Red Cross, knitting and sewing items for soldiers overseas, and with the auxillary Home Unit of Base Hospital No. 10, which assisted in forwarding packages and surgical supplies to those stationed at Le Tréport. Additionally, she oversaw the agricultural production at Lynfield Farm, where she and the children helped cultivate a large vegetable garden. Much of the farm’s produce was sold to the Red Cross to support the war effort, including milk, butter, eggs, peas, and spinach.

Account book of Lynfield Farm butter sold during the summer of 1917.

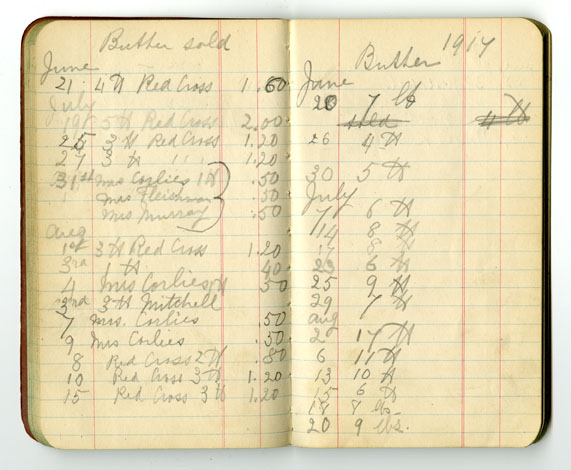

The family also participated in the U.S. Food Administration’s rationing campaigns, observing “Meatless Mondays” and “Wheatless Wednesdays,” in effort to conserve those items for soldiers that were easy to preserve and transport in bulk. Marjorie the younger observed in a letter to her father that the family was eating only brown [rye] bread as of August 1917, doing their part to help feed the soldiers overseas. Additionally, as part of the effort to conserve gasoline, Marjorie sold one of the family’s cars, a Studebaker, in the summer of 1917. During the coal shortage of the winter of 1917-1918, the schools in Philadelphia closed for several weeks and the Gibbon children had to complete their lessons at home until warmer weather returned. The children also did their part to support the war effort by selling liberty bonds with the Boys Scouts and raising money for the YMCA. The two eldest boys, Jack and Sammy, competed to see who could raise the most money.

Samuel Gibbon's letter to his father, describing how he raised money for the Y.M.C.A.

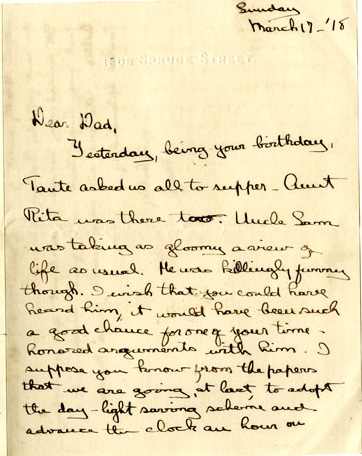

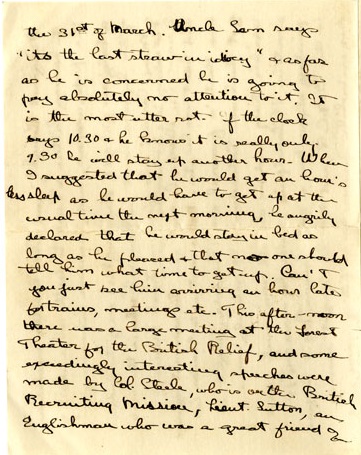

The eighteen months in which the United States was involved in the war also saw other significant national changes and events. A letter written by Marjorie the younger to her father describes her uncle’s reaction to the first nationally imposed daylight saving time:

“[…] Uncle Sam was taking as gloomy a view of life as usual. I wish you could have heard him; it would have been such a good chance for one of your time-honored arguments with him. I suppose you know from the papers that we are going, at last, to adopt the day-light saving scheme and advance the clock an hour on the 31st of March. Uncle Sam says ‘it’s the last straw in idiocy’ and as far as he is concerned he is going to pay absolutely no attention to it. It is the most utter rot. If the clock says 10:30 and he knows it is really only 9:30 he will stay up another hour. When I suggested that he would get an hour’s less sleep as he would have to get up at the usual time the next morning, he angrily declared that he would stay in bed as long as he pleased and that no one should tell him what time to get up. Can’t you just see him arriving an hour late for trains, meetings, etc.?”

Letter from Marjorie Gibbon (the younger) to her father, March 17, 1918

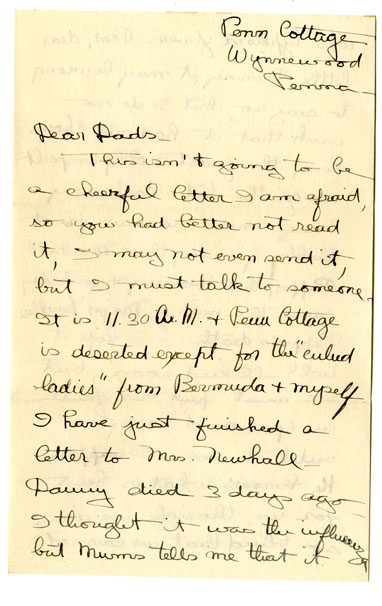

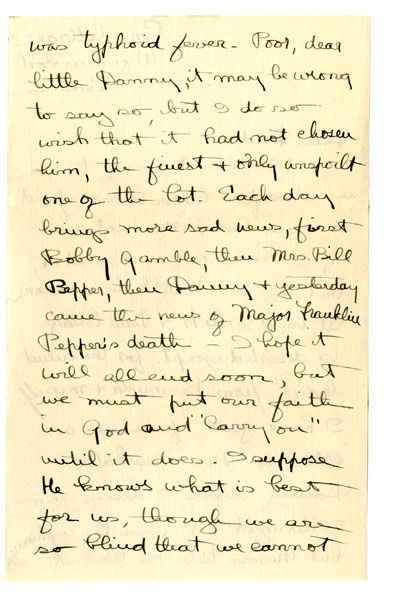

Other developments on the home front were of a much more sinister nature. Beginning in the summer of 1918, reports of Spanish influenza began to emerge within Philadelphia. By the end of September, the number of cases had reached epidemic proportions, shutting down the city’s schools, churches, theatres, and other public places. Conditions were made worse by the fact that great numbers of the city’s medical professionals and hospital staff were serving overseas. The impact of the outbreak was thus much worse than it otherwise might have been since many victims did not receive adequate medical attention. Hundreds of thousands of Philadelphia citizens had fallen ill and roughly 13,000 had died by the time the epidemic waned in late November. The Gibbon family was fortunate enough to emerge without any illness. From September through early November, Marjorie and the children stayed sequestered in the relative safety of the farm in Media. The children did not attend school for the month of October and they even avoided the train and other public transportation as much as possible, only using the car for necessary trips into town. Their letters from this time recount the almost daily news of deaths of friends and relatives.

Letter from Marjorie Gibbon (the younger) describing her experience of the Spanish influenza epidemic in Philadelphia, October 12, 1918

The epidemic trickled to an end in Philadelphia with the colder months of November and December. By then, much of the news from home recounted rumors of decisive Allied victories in Europe and finally, an approaching end to the war.

Just as Dr. Gibbon’s letters are valuable for their rich documentation of the experiences of Allied medical personnel during World War I, Marjorie Gibbon’s letters provide valuable insight about the Philadelphia home front. While American women and children faced less disruption to their daily lives in comparison to their European counterparts, they nevertheless experienced significant cultural and social change over the eighteen months the United States was involved in the war. As such, the Gibbon family papers prove valuable primary sources for their documentation of both Philadelphia history and World War I.

John and Marjorie Gibbon later in life, circa 1946