By Judith Bernstein-Baker, Esq.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2016 issue of Pennsylvania Legacies.

My mother’s citizenship certificate hangs on my living room wall; I framed it as a reminder of her immigrant journey to escape the pogroms and oppressive life her family endured in Poland before World War II. Today, as the executive director of HIAS Pennsylvania and an immigration attorney, I have the honor to oversee a staff that works with thousands of immigrants from all over the world. HIAS (the Hebrew Immigration Aid Society) is a nonprofit organization formed over 130 years ago to provide assistance to the influx of Eastern European Jews seeking freedom and opportunity. HIAS PA now provides legal services, refugee resettlement, education, and other supports to over 2,500 immigrants and refugees of all races, ethnicities, and nationalities per year. Citizenship assistance is one of our signature programs.

Citizenship has many advantages. Citizens are generally protected against deportation and can vote, gain access to certain government jobs, and sponsor family members who wish to immigrate. For low-income, foreign-born residents, citizenship means access to critical federal public benefits. To many, becoming a US citizen is the end of a long process and represents not just a legal status but a new national and cultural identity.

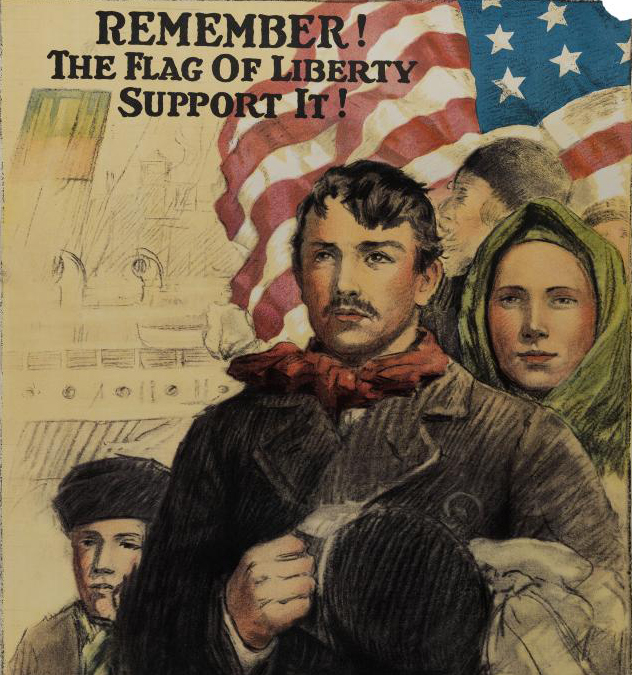

Immigration theme on a WWI era war bond, HSP Archives.

There are five ways to become a citizen. The first is to be born in the United States. Citizenship by birth, known as Jus Soli (right of the soil) and is guaranteed by the 14th Amendment of the US Constitution. The second, known as Jus Sanguinis (right of blood), is to acquire citizenship at birth abroad through a US citizen parent; a third is for a foreign national child to derive citizenship if his or her parent naturalizes before the child’s 18th birthday. A fourth pathway enables US citizen parents (or, in some cases, grandparents) to apply for citizenship on behalf of children born abroad.

But it is the fifth way—the naturalization process—that I wish to highlight by sharing the story of Mr. Sims (not his real name). Mr. Sims, age 67, came to the United States from Jamaica 16 years ago, sponsored by his daughter. He worked as a police officer in his native country and as a security guard in the States. A few years ago, he suffered head injuries in a car accident and reports difficulty in remembering things, especially recent experiences. Mr. Sims sought assistance in September 2015 at Pro Bono Citizenship Day 2015, an event in which over 100 attorneys, legal workers, and other volunteers assist newcomers in the application process. Citizenship Day is a coalition effort led by the American Immigration Lawyers Association of Philadelphia, and HIAS Pennsylvania has played a leading role in the event for the past eight years.

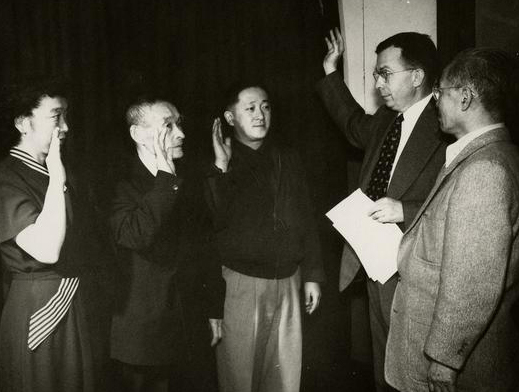

Individuals taking the Oath of Allegiance during the naturalization process, HSP archives.

First, Mr. Sims completed a 21-page-long N-400 form delving into his immigration and criminal history. Every applicant has their biometrics and fingerprints taken so the government may check multiple databases for red flags. Individuals must have “good moral character”—a broad concept that includes paying taxes and honoring child support obligations. Even for those with no background issues, the application can provoke anxiety. For example, part 12, question 23 asks, “Have you EVER been arrested, cited, or detained by any law enforcement officer (including any immigration official or any official of the US armed forces) for any reason?” (emphasis in the original). Mr. Sims reflected, “Well, when I was about 17 a neighbor told police I had stolen her pocketbook, and I was asked to report to the station. I went down there and the woman came and when she saw me up close realized it wasn’t me, so they let me go.” He answered “Yes” to 23 and attached an explanation.

In order to apply for citizenship, a foreign national must almost always be lawful permanent resident (a green card holder) for five years (three if married to a US citizen who sponsored the applicant). Individuals in the military need only wait one year; if serving during a time of hostilities, they may apply after only one day of service. They must also pay an application fee. Mr. Sims more than met the five-year waiting period but was concerned about the fee: $680. No longer able to work, Mr. Sims was receiving disability payments and medical assistance. Because his income was below 150 percent of the poverty level, he could apply for a waiver—which, of course, required a separate form and proof of income. The high cost of citizenship is a major impediment for many applicants who do not meet the fee waiver threshold.

After his application was processed, Mr. Sims received notice of an interview with an examiner, known as an adjudications officer (AO), employed by the United States Immigration and Citizenship Service (USCIS), who would test his knowledge of history and civics. The applicant must answer 6 out of 10 questions, randomly selected from a list of 100, correctly. To become a US citizen, one must also be able to understand, read, and write English. Comprehension is tested when the AO orally reviews the application, noting whether the applicant understands the questions and can answer them. The applicant must also read and write one to three sentences provided by the AO. For non-English speakers, this aspect of the test can be overwhelming.

Although he speaks English, reading and writing is a challenge for Mr. Sims following his accident. Applicants over age 55 who have had their green card for over 15 years may have the interview conducted orally, in their own language. But for individuals who simply cannot retain knowledge due to a mental or physical disability, even this effort is impossible. This is especially true for the elderly—many of whom show signs of deep depression and PTSD as a result of dislocation and loss—and pre-literate refugees. If a doctor or psychologist completes an N-648 form confirming that an applicant’s mental or physical condition prevents them from learning English and civics, these requirements are waived. Unfortunately, there are too few medical professionals willing or able to complete this form, especially since an interpreter must be used in arriving at a diagnosis. Elderly refugees who cannot naturalize within seven years lose their Supplemental Security Income—a key means of financial support for them and their families. Those of us who work with elderly refugees have urged USCIS to lower the standard for humanitarian immigrants or enable clinical social workers to complete N-648s. Without such policy changes, thousands of refugees who have suffered from war and persecution will be unable to naturalize and will be plunged into poverty.

Mr. Sims was convinced he could answer the civics questions. On the day of his interview, accompanied by his daughter, we met 20 minutes before the scheduled time. “Let’s practice,” I suggested. “Name one US state that borders Mexico.” He stared blankly. His daughter said, “You know, dad, Texas, where Tommy, your son lives.” Holding his head, he told me his headaches were getting worse. His daughter explained he was to see a neurologist the following day. I asked several other questions and circled back to the first one: “Name one state that borders Mexico.” Again, no answer. At this point, I urged Mr. Sims and his daughter to consider postponing the exam, but he was firm. “I want to take the test. I am praying on it.”

We were called to the interview room. After a review of the application, the adjudications officer asked the first question: “Name one state that borders Mexico.” Silence . . . then, “Texas.” My mouth dropped. Mr. Sims answered six out of the first seven questions correctly! He passed. He is going to become one of the more than 410,000 citizens of Pennsylvania naturalized since 1990!

But we weren’t done yet. The AO observed, “I see you answered you were detained in Jamaica. I need a police clearance from Jamaica before I approve your application.” I protested, “That was 50 years ago, and he was a minor. He had to obtain clearances of his criminal record when he applied to come to the US through his daughter’s sponsorship. Surely these factors and his history as a police officer should mean he is not required to get a police clearance from Jamaica, which is a very difficult process from the United States.” The officer was unmoved. I later wrote to the supervisor, who approved the application post interview.

Mr. Sims was not concerned, however. He was overjoyed he had passed the test and blessed the adjudications officer and me. His daughter offered to drive me to the subway. In the car, a CD was running, playing the 100 questions. “What is the name of the President of the United States now?” the CD droned. “Barack Obama,” chimed Mr. Sims. Smiling, he added, “I am going to be able to vote for the next one.”

Judith Bernstein-Baker was the Executive Director of HIAS Pennsylvania, a lead partner of Step Up to Citizenship, until October 2016. Step Up to Citizenship is a project of the Philadelphia Chapter of the American Immigration Lawyers Association, in collaboration with community partners, that provides pro bono legal assistance for those seeking citizenship.