by James Higgins

This article was published in the spring 2019 issue of Pennsylvania Legacies (vol. 19, no 1): Epidemics and Public Health in Pennsylvania History.

The centennial of the end of the Great War continues to overshadow the hundredth anniversary of an even deadlier catastrophe, the great influenza pandemic of 1918–19. Estimates of its global death toll top 50 million. In the United States, deaths exceeded 750,000 and may even have reached a million by 1922, when it is generally thought that the last localized outbreaks of the virus responsible for the pandemic occurred. By comparison, the First World War killed about 20 million soldiers and civilians, including 116,000 Americans (most of whom actually died of influenza). Pennsylvania undoubtedly experienced the worst epidemic of influenza in America, especially during its most acute phase, September 1, 1918–March 31, 1919, in which at least 67,000 of the commonwealth’s citizens perished. No other state suffered as many deaths or as high a mortality rate. At the municipal level, Pittsburgh, Scranton, and Philadelphia produced the highest mortality rates for major American cities. For scholars of the pandemic, Philadelphia continues to prove an important touchstone for the havoc the virus proved capable of wreaking.

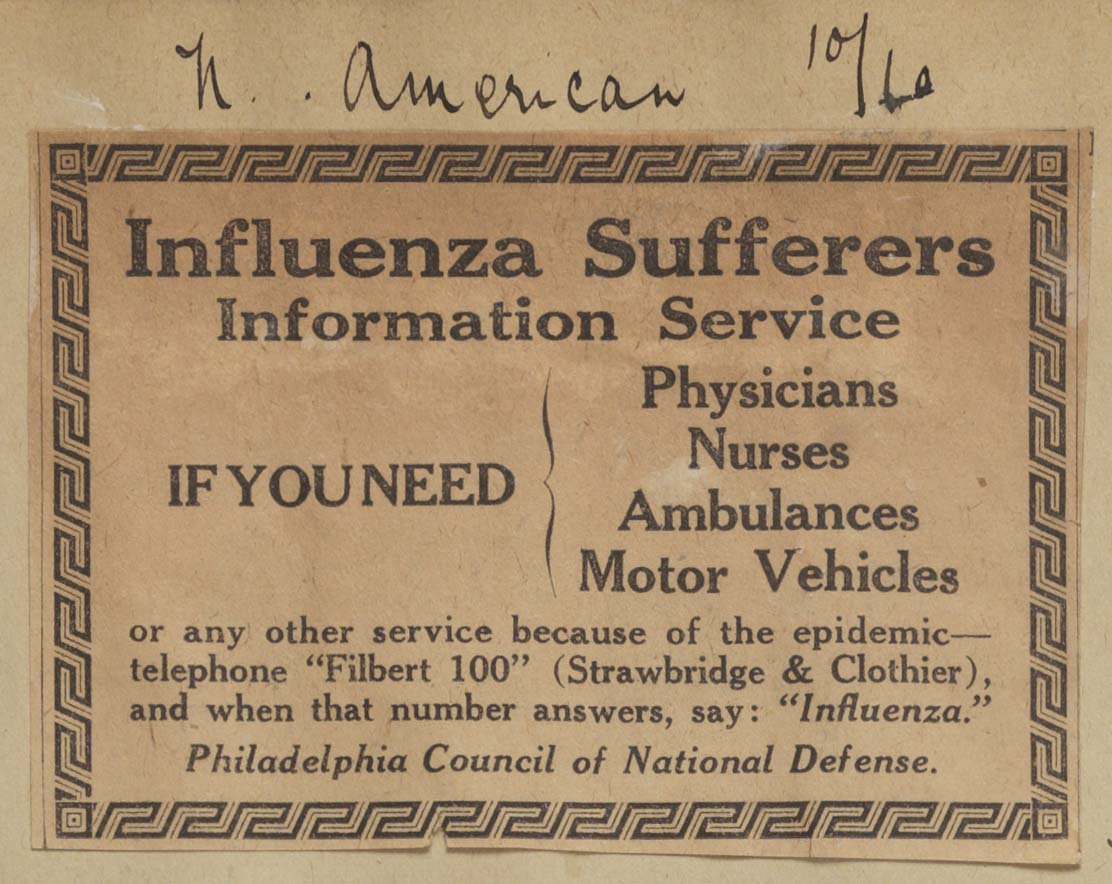

The Philadelphia Council of Defense took out newspaper ads like this one in the Philadelphia North American encouraging flu-stricken readers to call a hotline. October 10, 1918. Philadelphia Council of Defense Scrapbook, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

The population of Philadelphia soared between 1914 and 1918 as tens of thousands of people flooded the city looking for work in the metropolis’s war industries. The density of the city’s housing increased while sanitary conditions deteriorated and rates of infectious disease climbed. By the spring of 1918, the influenza virus that ultimately caused the pandemic had already begun to sicken people, though it almost certainly did not arise at Camp Funston, Kansas, as is often postulated by scholars who took an early report of influenza at the camp as evidence for the epidemic’s beginning among its soldiers. Instead, a particularly virulent form of the virus appears to have emerged in the port cities of England, perhaps among Chinese laborers employed by the British on the western front. It was from one of these ports, Liverpool, that a ship transported virulent influenza to Philadelphia in what was likely the first recorded instance of a highly lethal iteration of the virus alighting in North America.

The virus’s journey began on June 9, when HMS City of Exeter departed Liverpool for Philadelphia. The ship, a small passenger liner that the British pressed into service during the war as a military transport and cargo vessel, had a few dozen sailors aboard, many of them from India. A few days out of Liverpool, men began to fall rapidly ill with symptoms that included wracking body aches, fever, and coughing. Many of the stricken sailors developed serious cases of bacterial pneumonia as a sequel to their viral infection. By June 21, when the ship entered the Delaware River, grievously ill men lay throughout the City of Exeter, and an unknown number may have been buried at sea. Philadelphia health authorities quarantined the vessel before it could reach the city’s docks. The British consul in Philadelphia arranged for the ship’s crew to be moved from the vessel to Pennsylvania Hospital under the care of specialists from the University of Pennsylvania. Of the two dozen sailors taken off the ship, roughly a quarter succumbed in the hospital to the infection. Throughout the summer of 1918, more ships with sick crews arrived in New York City and Halifax. In a century of research, however, no scholar has produced evidence that another ship with virulent cases of influenza aboard docked in a port in the western hemisphere before the City of Exeter dropped anchor in the Delaware River.

American soldiers returning from France. The mass mobilizations of World War I helped spread the epidemic. 1918. Philadelphia War Photograph Committee collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Perhaps the virus on board the City of Exeter failed to ignite an epidemic in Philadelphia because of the stringent isolation measure. Or perhaps the virus had run completely through the crew before the vessel docked, leaving behind only cases of bacterial pneumonia. It is also possible that the virus had not yet evolved to optimize itself for transmission between people. In any event, Philadelphia avoided a general outbreak of influenza—as did the rest of the world—until August of that year. During that month, virulent influenza, its mutations having brought it to a level of infectiousness and lethality never matched before or since by an influenza virus, began to sweep across Africa, Europe, and North America. The epidemic in the United States began at the end of August 1918 in a naval facility in Boston. Within a few days, a few men turned up ill with influenza at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. September saw the number of cases build slowly in the city, and by mid-September several hundred cases might be found clustered in the working-class neighborhoods near the Navy Yard and other major industrial firms. At first, Philadelphia’s epidemic did not differ from that in other major American cities. Yet by the first week of October, roughly five weeks into the outbreak, Philadelphia’s mortality rate accelerated in a climb unmatched by any city in the nation—perhaps by any major city in the world. The reason for that acceleration lay in another event unique to Philadelphia’s outbreak.

Photograph of servicemen in the cafeteria at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, among the first spots in the city hit by the epidemic. March 11, 1919. Philadelphia War Photograph Committee collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

In addition to taxes, America paid for the war effort through Liberty Loans. These were designed with a dual purpose: they not only generated revenue but also raised morale by heightening the public’s patriotism. In all, there were four loan drives. The fourth, which began September 28, 1918, was the most successful. On that date, communities throughout America began the drive with parades. Even very small towns gathered the resources for flags, bunting, and marching bands to proceed down their main streets in great patriotic displays. Philadelphia hosted the largest and most spectacular of these parades. It ran 23 blocks, from Broad and Diamond Streets to Broad and Mifflin Streets, and consisted of several echelons of marchers, including military personnel, industrial workers, and Red Cross nurses. In addition to the usual stock of red, white, and blue onlookers might see at a July Fourth celebration, the Fourth Liberty Loan parade included such splendid sights as an airplane mounted on a float and under construction even as it made its way down Philadelphia’s main thoroughfare. At times, members of the crowd, especially boys, rushed a new piece of modern military technology—a new model British tank—and were allowed to clamber over the behemoth to inspect its tracks and gun ports. Above the city, a formation of new bombers (and in 1918, airplanes were still a rare and exciting sight) circled the city for an hour as anti-aircraft guns in hidden locations engaged them with “defensive fire” (shells fused to explode safely beneath the planes). Military units in the parade stopped to demonstrate bayonet and marching drills while speakers harangued the crowd with brief, pointed speeches about the sacrifices America’s men and women in uniform were making on the battlefields of France. The rally’s final flourish was its review by the governor, mayor, and members of the city’s most powerful industrial families. After the estimated 12,000 marchers disbanded, the parade’s at least 200,000 onlookers continued the festivities in singalongs and saloons before they returned to their homes and jobs. The virus, an invisible presence at the parade, had enjoyed an unprecedented opportunity to spread throughout the city and in the coming days announced its presence in a skyrocketing wave of sickness and death.

World War I soldiers returning to Philadelphia from France. 1918. Philadelphia War Photograph Committee collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

In the week following the parade, authorities counted over 1,100 deaths attributed to influenza, with dozens more unrecorded, especially among the ranks of war workers and the poor. In the midst of that first terrible week of October, the state department of health mandated a crowd ban prohibiting most gatherings related to entertainment venues and banned the sale of alcohol for all but medicinal purposes. The city extended the ban by closing schools and all houses of worship. While these measures likely reduced the rate of transmission in many other communities in Pennsylvania, it was too late in Philadelphia—the parade had already done the work of spreading the virus. Even before the crowd ban began, every hospital in the city was packed with the sick and dying. The city’s department of health opened 10 emergency hospitals, but with so many nurses and doctors serving in the military or sick themselves, few healthcare workers remained to staff them. As bad as the first week of October was, the next week was much worse, with roughly 3,000 deaths. The week after that saw well over 4,000 fatalities. The sheer number of corpses would have overwhelmed the city during even normal times, but with so many sick or away in uniform, the city simply could not cope.

It was at this juncture that Philadelphia’s outbreak transitioned from an awful, but managed, epidemic to a disaster unlike any other in the developed, urban world. In many cases, the bodies of the dead could not be removed from homes—and those that were, were stacked by the hundreds in a morgue with space for only 36 bodies. Cemeteries could not keep up with the flow of bodies and had no option but to allow the dead to be piled in sheds and on the open ground, often without coffins. People recalled the streets of the poorer sections of the city literally reeking with the smell of putrefying corpses, and the stench in homes must have been unbearable for the loved ones of the deceased. According to elected officials, panic creeped into the minds of the poor, for whom there appeared no end to the sickness and death that stalked their neighborhoods.

To the rescue rode the Roman Catholic archdiocese, the largest charitable organization in Philadelphia. The diocese acted on behalf of the city’s health department to pursue a two-pronged rescue effort. Hundreds upon hundreds of nuns moved into the emergency hospitals and throughout the neighborhoods of city. Their presence, and the swiftness with which they reacted to the diocese’s orders, effected an immediate change in the manner in which the sick and dying were treated. Until then, emergency hospitals had acted more as warehouses for the nearly dead than as treatment centers for the sick. With the nuns’ arrival, order was restored to an otherwise chaotic situation, and the quality of care for the ill rose. Those beyond hope, meanwhile, were offered a greater measure of dignity during their final hours. An account of the nuns’ deeds was recorded as a series of oral histories only a year after the epidemic passed, their steadfastness in the face of human suffering on a massive scale—to say nothing of the threat the virus posed to their own lives—a testament to their bravery and faith.

At St. Charles Borromeo Seminary in suburban Philadelphia, scores of students in their late teens and early 20s volunteered for duty in the emergency hospitals, where they worked alongside the nuns. Most of these young men, however, undertook an even more grim duty at the behest of the archbishop: taking charge of the many Catholic cemeteries in and around the city. The largest of the burial grounds was Holy Cross in Yeadon, just across the county line from Philadelphia. By mid-October, Holy Cross’s neat rows of monument stones and impeccably manicured lawns stood marred by an obscene collection of corpses, hundreds of which had lain for days, unembalmed and bloated, laid out in rows or thrown in piles on the grass and in various sheds. Poor Italians especially had almost no recourse to caskets and brought their dead to Holy Cross in pasta boxes, crates, and burlap sacks. During the first day of their service, the seminarians overhauled the operations of the cemetery office and began to excavate mass graves with hand tools. Still they could not keep pace, let alone make headway, with the dead. The monsignors in charge of the burials called upon steam shovels from nearby industrial installations to dig long trenches into which bodies, 60 at a time, were stacked two high in parallel rows. In the early 21st century, the rows of dead remain in Holy Cross in the X, Y, and Z sections. All told, more than 4,000 citizens were buried in mass graves by the seminarians.

A final task remained to the city and its seminarians: clearing bodies from homes and the city morgue. The morgue at 13th and Wood Streets was given priority. It required teams to clear it of bodies—and the fluids that had leaked from the 500 hundred corpses that had lain for days within. The situation was awful enough to constitute an obscenity; the few photographs taken of the interior show bodies with blackened faces thrown about the floors, while witnesses reported fluid seeping out to the sidewalk. Once again, the diocese sent laymen and seminarians to untangle the dead and cart them to cemeteries, where many received anonymous burial in mass graves. From the homes and hovels of the poor, and even from the sidewalks in front of homes when loved ones could no longer countenance the sight or smell of their dead, priests carried corpses to horse-drawn carts and from there to burial grounds throughout the city.

With the exception of the yellow fever epidemics of 1793 and 1798, Philadelphia never suffered an epidemic as severe as the outbreak of influenza in the autumn of 1918. Even cholera failed to produce the death toll or, importantly, the death rate that influenza exacted. Indeed, as measured by one-week mortality rates, the second, third, and fourth weeks of October 1918 exceeded the weekly mortality rates of even the worst weeks of the 1793 yellow fever epidemic. Philadelphia’s influenza outbreak was singular in the history of the nation and the modern, western, urban world, and no better example exists of the violence the virus can produce under the right conditions.

A century after the outbreak, many of the locations that played a prominent role in the epidemic remain. The morgue is now an annex building of the parochial school system, though it is doubtful the students or teachers know of their church’s role in clearing the dead from what became their classrooms, nor can most visitors to Holy Cross envision the trench graves that once snaked across the lawns. The Navy Yard, less busy than it was during the Great War, still tends to the nation’s warships, and the tree-shaded campus of St. Charles Borromeo continues to train young men for the priesthood, though the only reminders of their forebears’ service to the city during the epidemic lie in the school’s archives. Yet, even a century removed from the greatest of disasters in the city’s long history, historians and public health experts draw upon its story to remind leaders and the public that what once happened in Philadelphia might happen again were a new, virulent influenza virus to suddenly appear.

James Higgins is a historian of medicine and concentrates especially on the history of the influenza pandemic in Pennsylvania and Texas. He now lectures at Jefferson University in Philadelphia and Rider University in Lawrenceville, New Jersey.