The following article was written by HSP volunteer Randi Kamine and is being posted on her behalf.

It happens, at times, that a large HSP collection yields an interesting, smaller “sub-collection.” This is the case with the McCall family papers (Collection 4088). Several previous blogs explored the experience of Dr. Peter McCall Keating through letters found in the collection. In the year before the United States entered the First World War, Keating went to France to work on one of the first train ambulances.

In processing the inventory of the McCall collection, another interesting story emerged. Ninety-three documents detailing a suit brought by Peter McCall against General John Jay Jackson, Sr. were nested in the many business and personal correspondence and legal papers in the collection. The parties went to court over a land dispute concerning property in Walker Creek, Wood County, Virginia (now West Virginia). There are several points that make a closer look at the documents regarding this dispute interesting.

Peter McCall, photograph by F. Gutekunst (undated), McCall family papers

(Collection 4088), Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Following the court case as it wends its way to its conclusion, the researcher gains insight into the mid- nineteenth century American court system. The matter is complex: many deeds to explore, many lawyers involved, and a thousand acres at stake. Inheritance in the United States is, and was in the mid-19th century, a matter of state law and each state has its own history of the law of inheritance. The researcher who is interested in real property and inheritance law will benefit from delving into this section of the McCall collection.

The length of the dispute is what first garnered my attention. The first HSP extant letter, written by Peter McCall, is dated February 12, 1852. The last letter is dated May 19, 1868. Sixteen years. The case was active before, during, and after the Civil War. The disputed property, Walker Creek, Wood County, was in the state of Virginia at the beginning of the process, and was in West Virginia at the end.

One of the elements that make this a 19th century story is how arduous was that of the communication among the principals. Yes, in this day and age it is not uncommon for land disputes to last several years. And perhaps some of us have faced the frustration of dealing with some or other activity with lawyers or the court system and the delays that ensued. But the glacial pace of this dispute has a different tone and character. A dispute today lasting sixteen years will produce perhaps tens of thousands of documents and communications. In the years it took to resolve the McCall issue, far, far fewer communications have come to light. Some letters begin with the writer asking if the recipient ever received their letter. In beseeching an answer, some people wrote that they hadn’t heard from the recipient, or the court, in months or years.

Another interesting aspect of this story is the eminence of the leading characters. The plaintiff is Peter McCall (1809-1880), mayor of Philadelphia from 1844 to1845, and esteemed Philadelphia attorney. The McCall collection notes the many accolades he received during his lifetime. One of Peter’s lawyers was Arthur Inghram Boreman, member of the Virginia House of Delegates, the first Governor of West Virginia, and a United States Senator. In all, there were at least four other attorneys working with McCall at one time or another.

The defendant is a Virginia (and later West Virginia) personage, General John Jay Jackson Sr. (1800-1877). On the face of it, Jackson was a man of sterling character. Born in Parkersburg, Virginia (now West Virginia) into a prestigious family, he was a graduate of Princeton University, a Virginia District Attorney in Wood County, and a member of the House of Delegates of the State of Virginia. But was he a knave hiding behind the demeanor of an upstanding citizen? Peter McCall would have history deem him as such.

Interest in this dispute also lies in the personal observations made by the writers of the letters. Although obscured by the stiff language, and the fact that the participants are not overly emotive, the letters do take us into the thoughts and the feelings of those involved. Here are the series of events that led to the dispute:

1785 - A tract of 1000 acres was granted to one William Tilton on Wood County, Virginia. “Said tract and many others were transferred … converging until the title became vested in the heirs of Archibald McCall.” [1860 “charges” document.]

1843 - Archibald McCall dies. Robert McCall inherits the land. Peter McCall is the nephew of Robert and is one of Robert’s potential beneficiaries. There is evidence that as early as April 1838, Robert McCall asked General Jackson to take charge of the tract of land and to try to sell it. Jackson acknowledged this request.

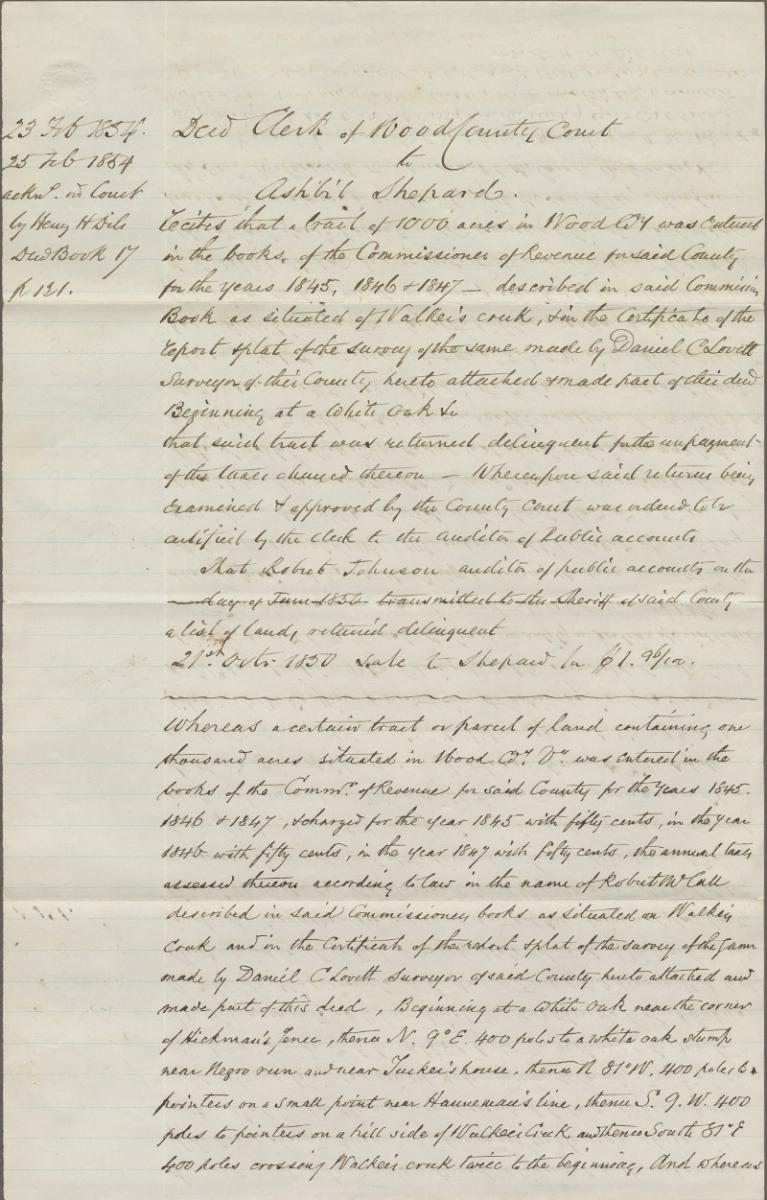

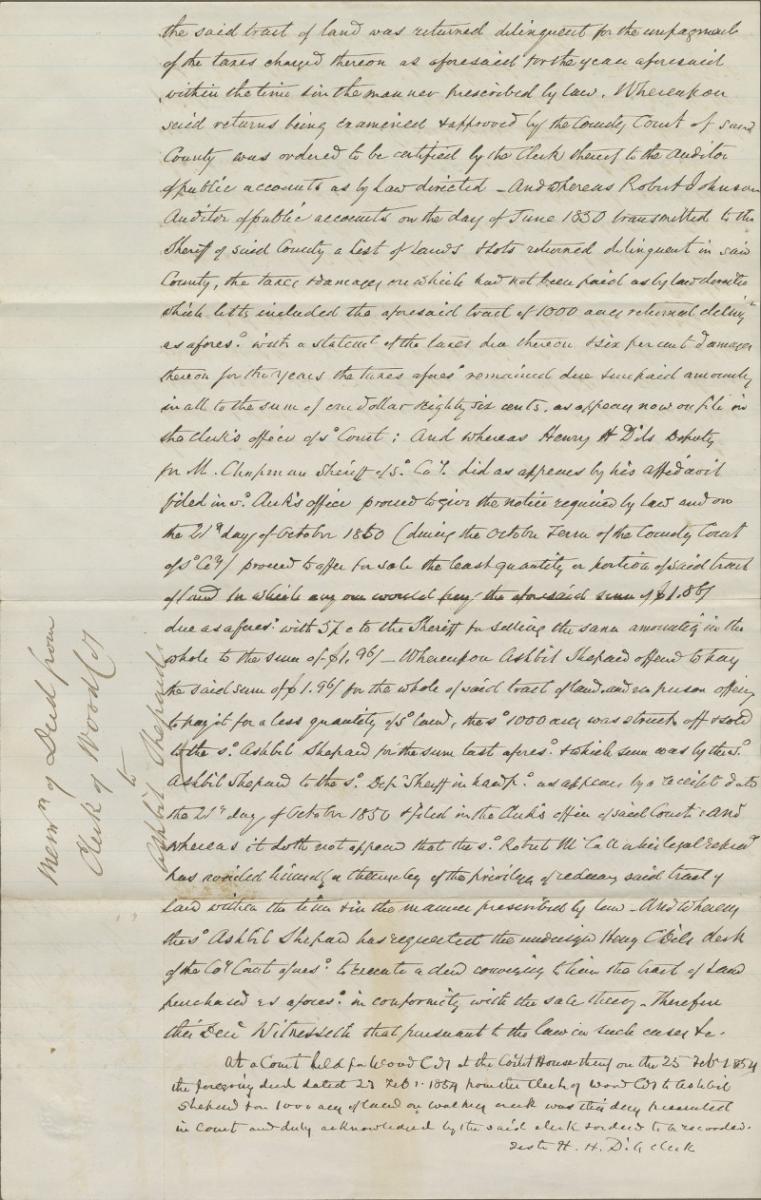

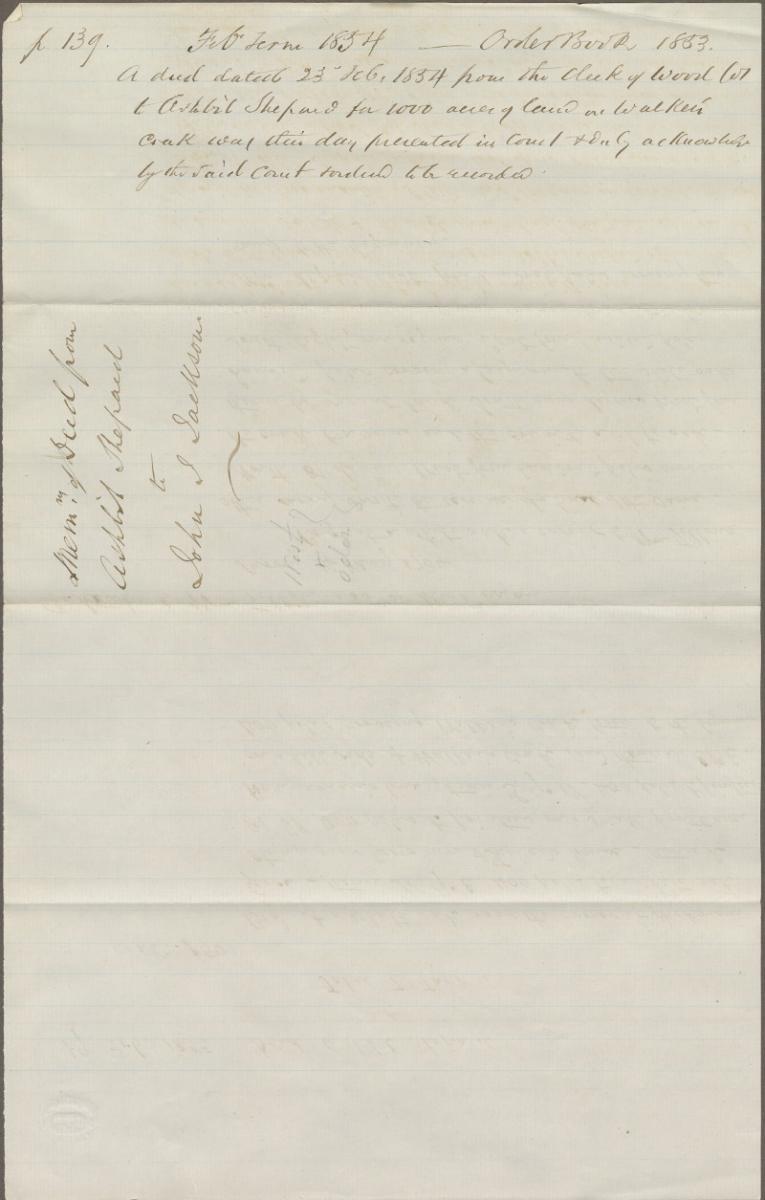

1854 - Robert McCall dies. In November 1859 a copy of his will is admitted to probate. It was discovered during probate that in October 1850 the tract was sold by the municipality for delinquent taxes to one Ashbil Shepard and in February 1854 the clerk of Wood County conveyed the deed to Shepard.

Memorandum of deed from Clerk of Wood County to Ashbil Shepard, pages 1 and 2 (circa 1855),

McCall family papers (Collection 4088), Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

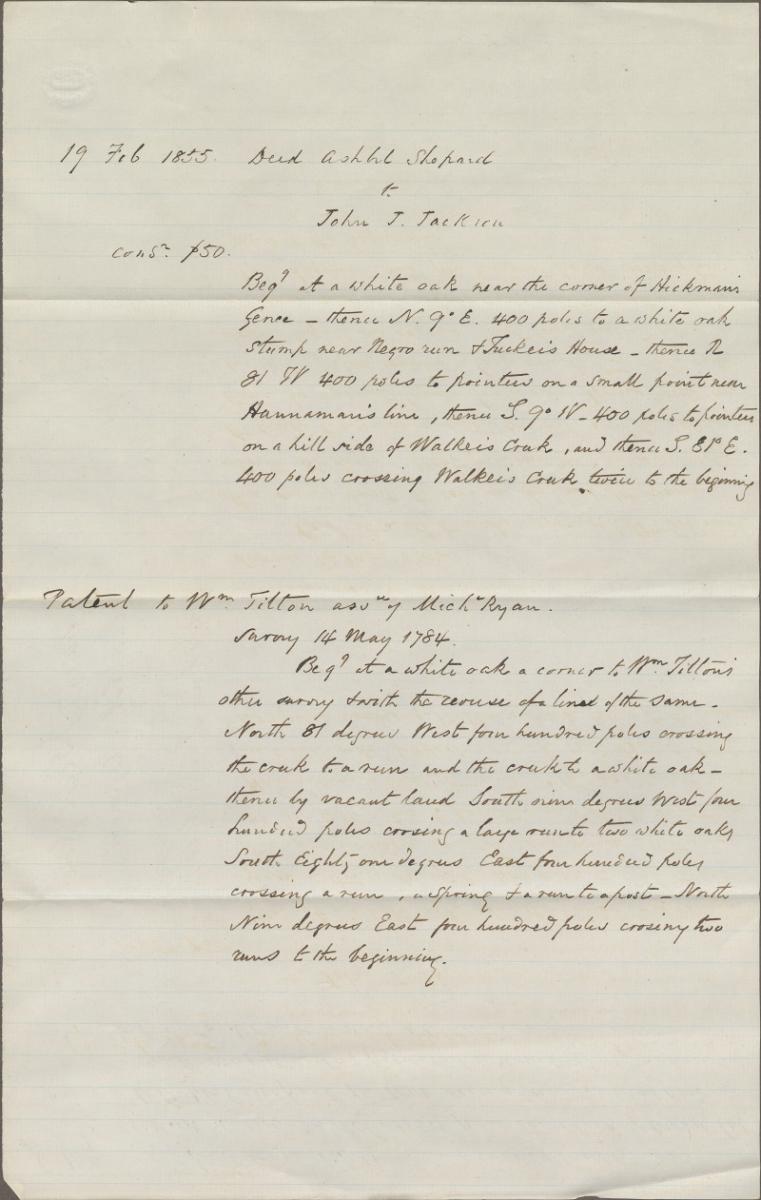

1855, February - Shepard conveyed the deed to General Jackson for $50.00. Robert McCall was not aware of the sale for taxes and his descendants were not aware of the conveyance to Jackson until Jackson came forth with the deed.

Memorandum of deed from Clerk of Wood County to Ashbil Shepard, pages 3 and 4 (circa 1855),

McCall family papers (Collection 4088), Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

And so the long, engrossing, process to determine who owned the land begins.

HSP has ninety-three extant letters emanating from this suit (per mid-1800’s practice, copies were made of letters written by McCall and sent to others).

The earliest letter, dated February 12, 1852, is from Peter McCall to Amos N. Meylut, a lawyer. That letter does not give a hint of the problems that were going to surface. It is simply a request to set the wheels in motion to execute Robert McCall’s will. To the reader who knows what is to follow, there is a foreboding. “Oh no,” one wants to warn Peter, “prepare yourself for a long, aggravating adventure” as he innocently sets the suit in motion.

The next letter in the collection, dated December 25, 1854, was written by Amos N. Meylut to Peter. He tells Peter about his investigations into the matter. Meylut claims that when Robert McCall’s land was under the care of General Jackson he, Jackson, paid the taxes on the land for a time, but eventually it was Jackson, who “suffered Mr. McCall’s 1000 acres to be sold for taxes.” Further, he informed Peter that his investigations showed that Robert was informed of the sale and wanted his land back from Jackson.

From Jackson’s point of view he was not acting as the agent of Robert -- that while he paid taxes on the land he was never reimbursed by Robert, freeing him from any agency. The McCalls claim that Robert assigned him as agent as far back as 1838, “to sell said tract, the bring suits out oust and turn off trespassers and settler’s if any.” Apparently Jackson acknowledged this request by letter.

Meylut had an opportunity to speak with Sheppard about the matter in August 1856. In a letter to Peter he writes, “He (Sheppard) says that at first, he understood from General Jackson that he (Jackson) was the agent or attorney for the Heirs of Robert McCall, but when he made the transfer he found Jackson was purchasing [the property] in his own right.” So, no clarity from this contact with Sheppard.

In December 1855, McCall’s attitude toward General Jackson is bitter. McCall writes, to James M. Stevenson, Esq, that Jackson “has been so extraordinary and so hostile to our interests that we think …our case should be placed at once in the hands of a gentleman of honor and ability who may forthwith make the necessary steps to obtain our rights in the event of any hesitation on the part of General Jackson to do what is right. … Withholding the title would be clear fraud.”

There is a gap in the letters during the Civil War. The last letter before the Civil War was written October 15, 1860, eight years after the initial letter. It was written to Peter McCall from attorney Arthur Inghram Boreman, acting on McCall’s behalf. In it, he writes, “I shall prepare your case against Mr. Jackson, and I cannot now see any reason why it may not be successful. I should have brought the suit long ago…” After the Civil War, things are still at a standstill. In a letter written in May 1864, Peter McCall says to Stephenson, “I am anxious to know in what condition the suit which Governor Boreman instituted and with which you are associated against General Jackson for the 1000 acre tract in Wood County is at present.”

As the months turn into years, Peter’s frustration mounts, and it is reflected in his correspondence. He has a terrible time just determining how the suit is going or even if it had been heard before the court. He was promised by his lawyers time and again that the matter would be on the next agenda of the Wood County Circuit Court. Time and again it was delayed under unknown or murky circumstances. In only one letter, dated May 20, 1864 from Peter to Stephenson, is the Civil War mentioned as a possible reason for the delay. “The unsettled condition of affairs growing out of the war may have retarded the prosecution of the case.” It is hard to say if this is Peter reaching for straws or in fact the war might have been a factor.

His cousin George McCall gets into the act. He writes, from Marietta, Ohio, “In the beginning of the week I went to Parkersburg [about 15 miles] and made several attempts to have an interview with our council James Stephenson, but failed.” He then went on to write that he “did the next best thing,” and went on to see General Jackson’s lawyer. He was told that Peter’s suit had been dismissed (! ) “for want of security for costs.” George went on to say, quite emphatically, that he thought there had been great neglect in the case perpetrated by the several lawyers engaged to help in the matter. At long last, in a letter from early January 1865, on the State of West Virginia stationary, Governor Boreman tells Peter that his suit had indeed been dismissed due to a technicality -- a security bond, a required court fee, was never paid to the court.

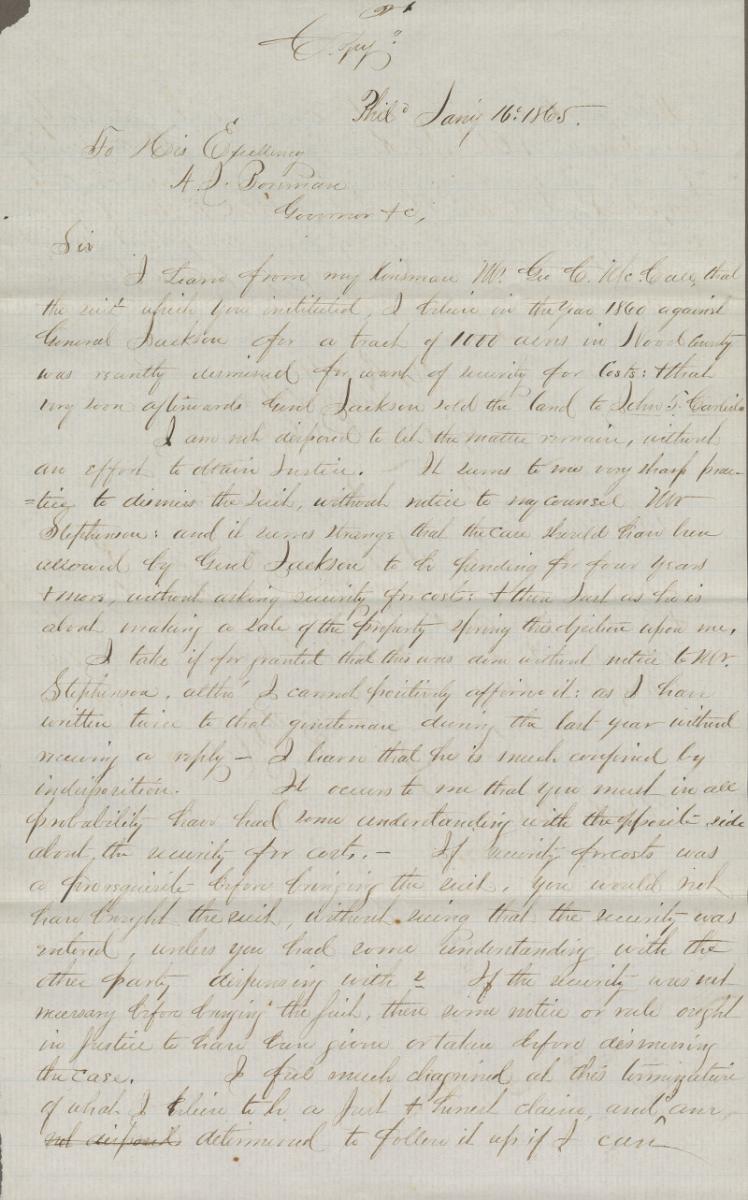

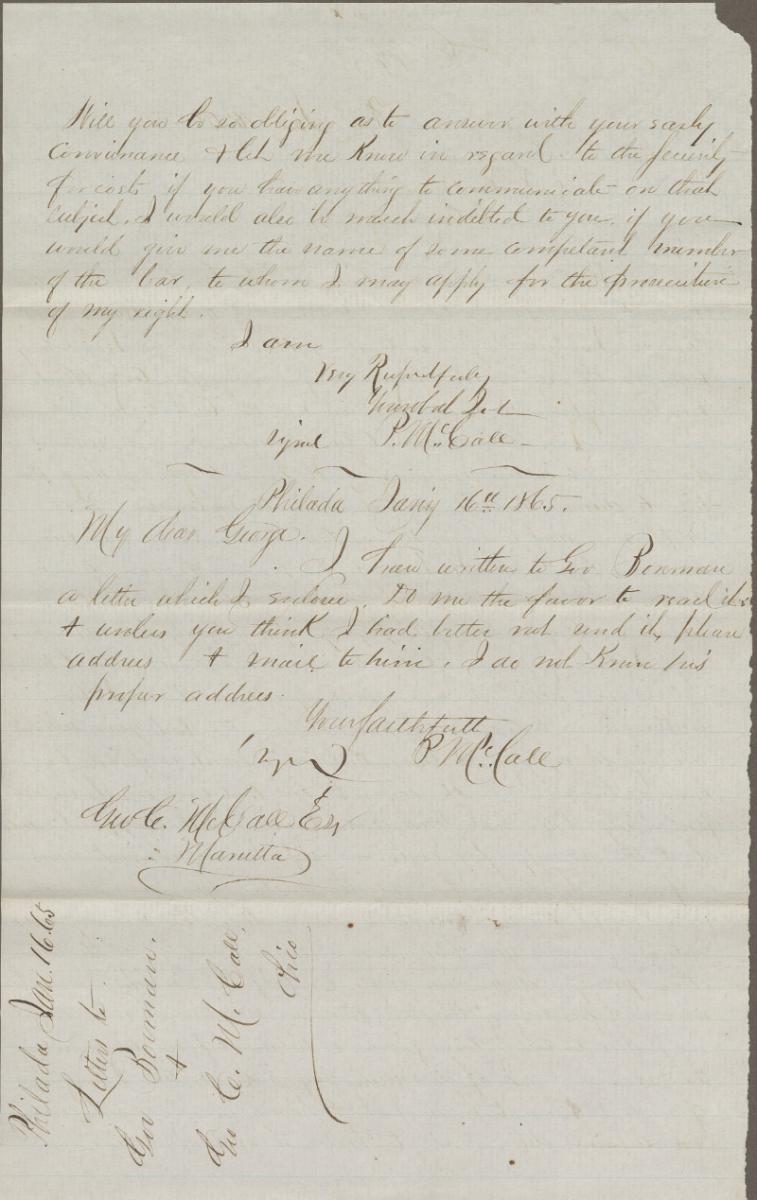

Peter is determined to “obtain justice,” he writes to Boreman in January 16, 1865. He thinks it’s “strange” that his case was dismissed without notice to his counsel, Mr. Stephenson. Peter suspects funny business. He believes that Jackson deliberately allowed “the case to be pending for over four years and more without asking for security for costs” and that just as he, Jackson, is preparing to sell the property he caused this glitch to be known to McCall. Peter writes to Governor Boreman, “It is to me very sharp practice to dismiss the suit without notice to my counsel.”

Peter McCall to Governore A. J. Boreman, pages 1 and 2 (16 January 1865), McCall family papers

(Collection 4088), Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

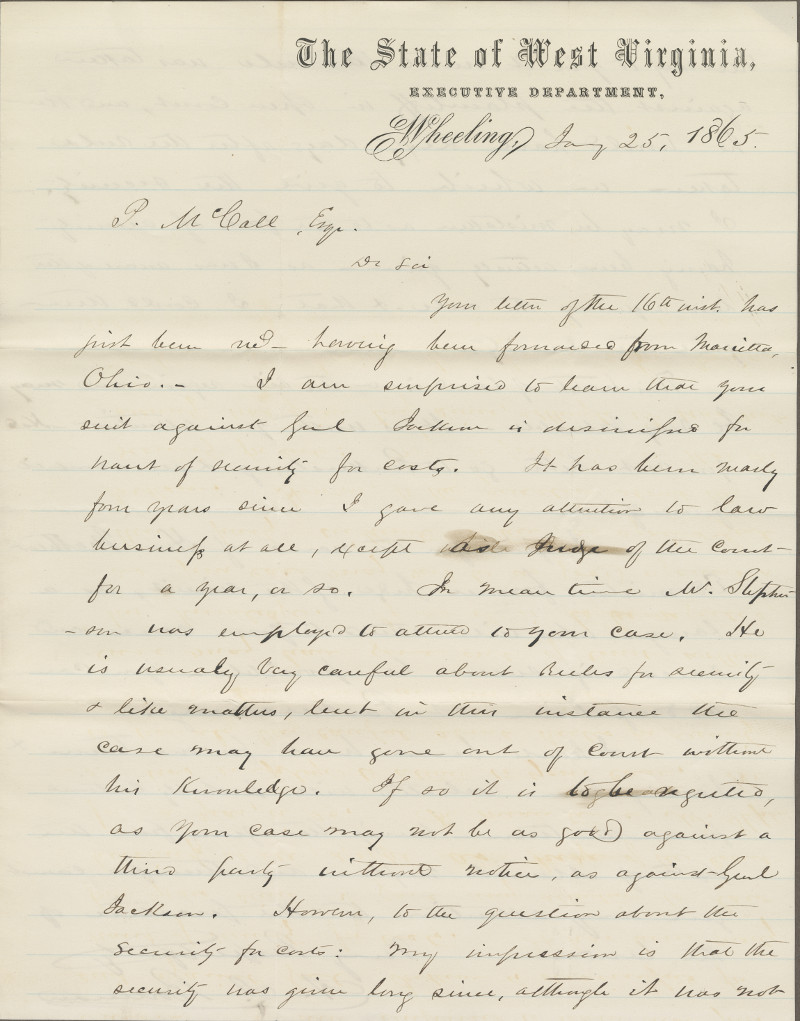

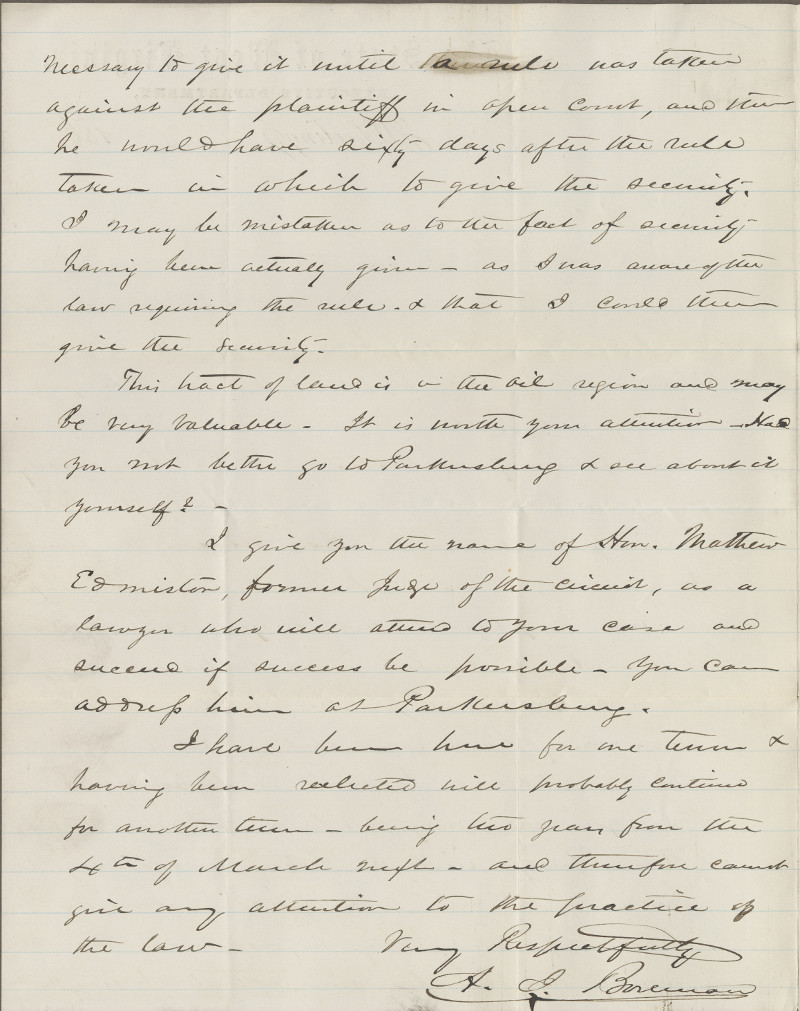

Governor Boreman relies, “I am surprised to learn that your suit against General Jackson is dismissed for lack of security for costs.” Not so subtly, he throws shade on Stephenson: “In the meantime, Mr. Stephenson was employed to attend your case. He is usually very careful about rules of security.” But Peter was not to give up so easily. And for good reason. In a January 25, 1865, letter from Governor Boreman, something new is introduced into the mix. Oil is mentioned for the first time. Oil had been discovered in Wood County. Walker’s Creek, it became clear in the early 1860s, lay between two oil producing areas. The B & O Railroad went through Walker Creek and was used as an oil transport stop. This notably increased the land’s value.

Governor A. J. Boreman to Peter McCall, pages 1 and 2 (25 January 1865), McCall family papers

(Collection 4088) HIstorical Society of Pennsylvania.

From the "Visit Greater Parkersburg" website:

By 1860 oil fields were discovered in the town of Volcano. These fields proved to be active for more than a decade and an oil pipeline was built from Volcano to Parkersburg. Wood County became a leading oil market.

Volcano, now a ghost town, was located very close to Walker Creek. After the finding of the dismissed suit, General Jackson sells the land for $200 an acre. Peter is determined, not to get the money that was paid to Jackson for the land, but get the land itself back. So he renewed his suit. Jackson, manewhile, used the time honored legal strategy of delay. George writes to Peter that,” The General appears to have adopted a course of (?) inactivity, The lawyer Matthew Edmiston wrote to Peter in July, 1966 that after Peter filed his second suit: “General Jackson has been very dilatory in forwarding his answer to our bill or our supplemental bill.” There is a lot of pleading from Peter to his several attorneys asking when the suit will be heard again.

Alas for Peter, the end of this legal journey is near. In a letter dated December 1867 Peter confirms to Edmiston that after apparently getting the bond issue solved, Peter received word that the Circuit Court of Wood County decided his suit against General Jackson in Jackson’s favor. The circuit judge decided that Jackson’s agency “was not made out.” Peter is not happy. He asks Edmiston for the name of the circuit judge and what his standing is as a lawyer. He writes, “I am aware of General Jackson’s influence in your county and am therefore somewhat desirous of knowing the caliber of your circuit judge.” He is thinking of an appeal, but there is no indication from these letters that he pursued that option. Fortunate General Jackson. One wonders if he hit pay dirt with his valuable acquisition in the middle of two oil fields. Further research on Walker’s Creek could be very interesting. As for Peter, to add insult to injury, correspondence in 1868 primarily has to do with paying fees owed to his attorney Governor Boreman.

Biographies of Peter McCall and General Jackson that I have been able to find do not include this property dispute. I suppose that in the scheme of things, it may not have a big impact in either of their lives. However, reading these letters gives the reader a feel for the characters of the men. At times the language is somewhat formal, but the traits of determination and self-righteousness show through on McCall’s part. It can’t as easily be determined the true character of Jackson. Certainly, his official biographies and obituaries, do not hint of what McCall feels is his true nature.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Notes

- The letters referred to in this blog can be found in the finding aid for Collection 4088, inventoried under the series “Legal matters.”

- This telling of the land dispute does not give a full accounting of the ins and outs of the quarrel. A close reading of the letters could help the researcher track these developments and shed light on property rights in the nineteenth century.

- It should also be noted that Peter McCall’s legal career included not only work on inheritance and real estate. He entered into the cultural and political world of the city. The collection is of wider interest than the Walker Creek dispute. Hundreds of legal documents can be found in the full collection.

Lawyers mentioned in the letters:

- James M. Stevenson (sometimes spelled Stephenson)

- Amos N. Meylut

- Judge Matthew Edmiston

- Judge Lee -- “Judge Lee is here come down we will advise you as to Peter MCall’s case. To Major George McCall from Judge Edmiston. Telegram dated January 27, 1865.

- Arthur I. Boreman

- J. M. Steed

Sources and related documents:

- Robert Enoch, local historian, Parkersburg, W.V. Visitors’ Bureau.

- University of Pennsylvania Law Library

- McCall family papers (Collection 1786)

- George A. McCall papers (Collection 1635)