This blog was written by Fiona Bruckman, a summer intern from Vassar College.

The idea that urban green spaces can have a positive impact on public health has been interwoven throughout Philadelphia’s history since the city’s establishment by William Penn in the 1600s. Penn intended for his New World experiment to be a “greene Country Towne,” and he turned to parks to improve upon the grittiness of early modern London where he was raised. Penn included five public squares in his grid system layout for the city, believing that they would contribute to his quaint agrarian vision. Despite Penn’s vision, however, Philadelphia's parks have not always been accessible to all.

The commissioning of what would become Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park occurred in the 1800s in an effort to protect Philadelphia’s water supply from the upriver industrialization that threatened it. The park originated as a private estate called Lemon Hill, which was owned by the merchant and real estate developer Henry Pratt. The 1856 book Lemon Hill in its connection with the efforts of our citizens on Councils to obtain a public park recalls the 1843 purchase of the Lemon Hill Estate by the city. This purchase was “warmly recommended by the College of Physicians of Philadelphia; as a sanitary measure, on account of its importance in the preservation of the purity of the water.” The park’s ownership transferred to the Philadelphia City Council in 1854 with the passage of the Act of Consolidation. The park was officially dedicated as “Fairmount” in 1855 with a reinstated responsibility to “preserve the water from contamination and secure at the same time in the most eligible spot near the city, a pleasure-ground commensurate with the demands of its crowded population.”

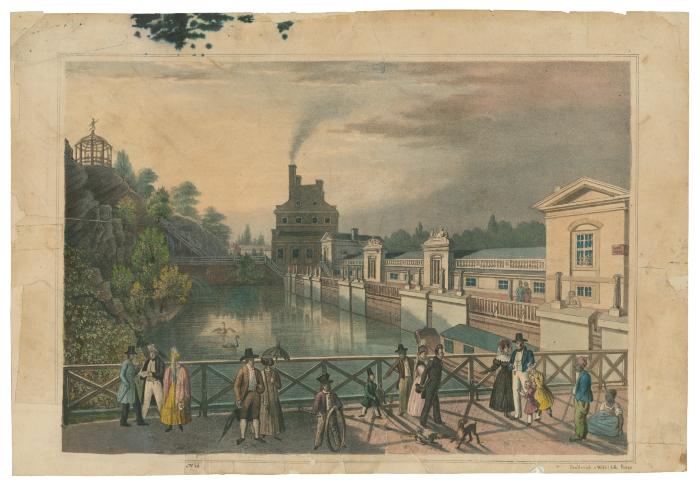

An 1833 lithograph shows a view from the floodgates looking toward the eastern side of Fairmount Waterworks.

Later in the book, the author argues on behalf of the park’s expansion and protection, given Fairmount’s limited funding during that period. He lays out a fantasy in which the park serves as an all-healing haven for the city’s masses. He envisions how people would come to Fairmount for “an hour’s repose before evening, from the dust and toil of that great city; here they were gaining refreshment and strength for the coming morrow.” Both escape and wellness were central concerns in the fight for Fairmount’s increased funding. He believes that living within the confines of the city affects not only physical laborers but the ones “whose toil is in the brain,” stating “Through confinement and want of exercise our professions are filled in the cities of this country with physical apologies for men.” A well-kempt park accessible to all, he proposed, would be the perfect antidote to the city’s supposed declining health. Accessibility to all, however, also proved a fantasy according to the 1886 publication Lemon Hill and Fairmount Park: the papers of Charles S. Keyser and Thomas Cochran. The book’s forward, authored by Horace J. Smith, documents some complaints which arose from Philadelphians in the late 1800s claiming that Fairmount was a “a rich man’s park” . . . “inaccessible to the people.” When the City Council was granted control in 1855, it assumed the grounds were “in their actual possession,” and they ordered them to be enclosed, thus excluding the Philadelphians to whom the park was originally dedicated.

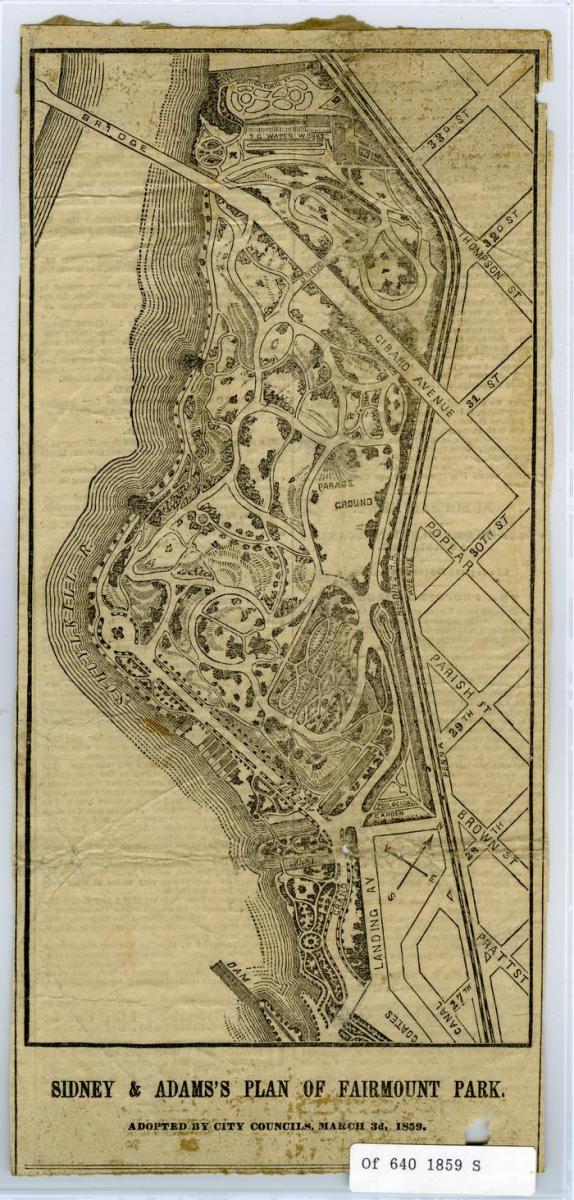

Sidney and Adams Plan of Fairmount Park, adopted by Philadelphia City Council on March 3, 1859

While the park quickly became a contested space over which different groups tried to exercise control, the original proponents of the park had the opposite goal in mind: the park was to become an equal-opportunity healer. Charles S. Keyser, credited as Fairmount’s “creator,” writes of the park that “The air that blows about it is the common property of the poorest as of the wealthiest” and “the water that flows along it is the common heritage of all.” He continues to exalt how “Its verdure grows for the eyes of the little child ignorant for the meaning of property, and for the old man who has long outlived the hope of acquiring it.” Keyser’s comments allude to a nostalgia felt among the city’s people for not only the agrarian vision on which Philadelphia was founded, but for pre-agrarian times free from property and societal division. His comments read as a cry for communal experience, yet somewhere in Fairmount’s history this vision became muddled by the conflicting vision to use the park as a resource for economic development.

David J. Kennedy landscape painting of Sedgely mansion, which the inscription states "was situated on the East bank of the Schuylkill...north of and adjoining Lemon Hill"

The establishment of Philadelphia’s public parks, particularly Fairmount, has always been seen as a matter of preserving public health. At the same time, however, these parks historically excluded large demographics of Philadelphia's population. The history of Fairmount Park illustrates how sometimes the fraction of the “public” that public health initiatives aim to protect, is indeed a fraction, and oftentimes the most privileged fraction least in need of restorative care. As Philadelphia and the world enter an age of ever-increasing urbanization, the healing properties of urban greenery will be much discussed. It is in these conversations that we must remember the message of Fairmount’s founders to include the entire public in the city’s quest for improved public health.

Fiona Bruckman is a sophomore at Vassar College pursuing a degree in history.