When archivists and records management types talk about documents, we often talk about their "life cycle." The life cycle of a document can be a complex system of users, creators, and formats, but at its most basic, the life cycle has two parts: 1) useful to original users for the original purpose and 2) not useful to original users for the original purpose. When a document enters the second phase of its life cycle -- its afterlife -- it becomes potential archival material. In a document's afterlife, it is of value to an entirely different set of people. Letters are no longer valuable to their recipient or writer, but they are of great interest to historians, family members, and other researchers. Bills are no longer needed by the company that issued them, but people studying the history of that company might want to take a look.

And the same is true of cemetery records. These documents were originally intended to help a cemetery keep track of burials, schedule lot maintenance, decide how deep to dig graves, and generally keep a handle on all aspects of the business. But now, records like those from the Woodlands Cemetery Company in Philadelphia are of great value to genealogists and family historians.

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania has a few cemetery collections, including Woodlands, the Ronaldson Cemetery, the Sandy Bank Cemetery, and the Methodist Episcopal Union Cemetery. (For a better idea of our materials, search our online catalog, Discover, for "cemetery.")

The Woodlands Cemetery Company records include information that might be of interest to genealogists in several different formats. The financial records can tell you who paid for which graves, who paid for perpetual care of lots, and who requested special care of additions to their family lots. This collection also has a large amount of correspondence specifically about burials and the care of lots. These letters are the place to look if you want to know how a lot was inherited by ancestor X or who paid for flowers to be annually placed on ancestor Y's grave.

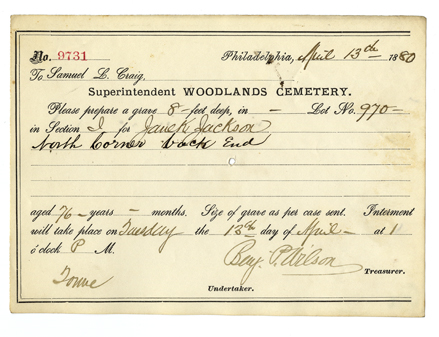

But the heart of this collection is thousands of small cards like this one:

These burial records are organized by year and span from 1845 to 1975, so if you know the year in which your ancestor died, they can give you quite a bit of information about their death. A typical burial permit in this collection contains the following information:

- A record number, which can correspond to a work order, piece of financial documentation, or other internal paperwork elsewhere in the collection.

- A date, usually not the date of death, but rather the date on which someone filled out the paperwork to request the burial.

- Location of the lot and grave, sometimes more specific than others.

- The name of various cemetery staff, like the superintendent and treasurer named above.

- Depth of the grave. This was important since many families used the same lot for generations, so they would specify a depth to entire the most efficient use of the land. If your ancestors were at 12 and 9 feet, your grave would have to be at 6.

- The name of the decedent. In cases of stillborn or very young babies, this will often be blank or will simply say "Smith baby" or "stillborn child of John and Margaret Smith."

- Age of the decedent.

- Date of burial.

And of course some burial records deviate slightly from this format. Some include information about the funeral service, the cause of death, or instructions to the gravediggers. So even if you don't know what you're looking for, it's good to browse. While processing this collection I was surprised multiple times by being able to piece together narratives, like a mother dying from complications of childbirth and 19th century healthcare (which I mentioned in this blog post over at Fondly, Pennsylvania, HSP's archives and conservation blog).

Cemetery records might seem morbid or depressing at first glance, but for genealogists the best way to discover how someone lived might be to start with their death.