I Got My DNA Test Results: Now What?

Sydney F. Cruice Dixon Appears on NBC10

Historian Edward Lengel reflects on the Lost Battalion of WWI

HSP’s Lee Arnold Receives Genealogy Award

Journalism as Protest: Voices from Young Black Philadelphians in the Late 1960s

By Madison Arnold-Scerbo, an intern from Haverford College

“We feel the future belongs to us, but we must take action to make sure we get ‘that’ kind of future, not the kind those in power now are willing to ‘give’ to us. Nobody gives you anything, especially freedom – this you must fight for” (The Black Ghetto, Sept-Oct 1968)

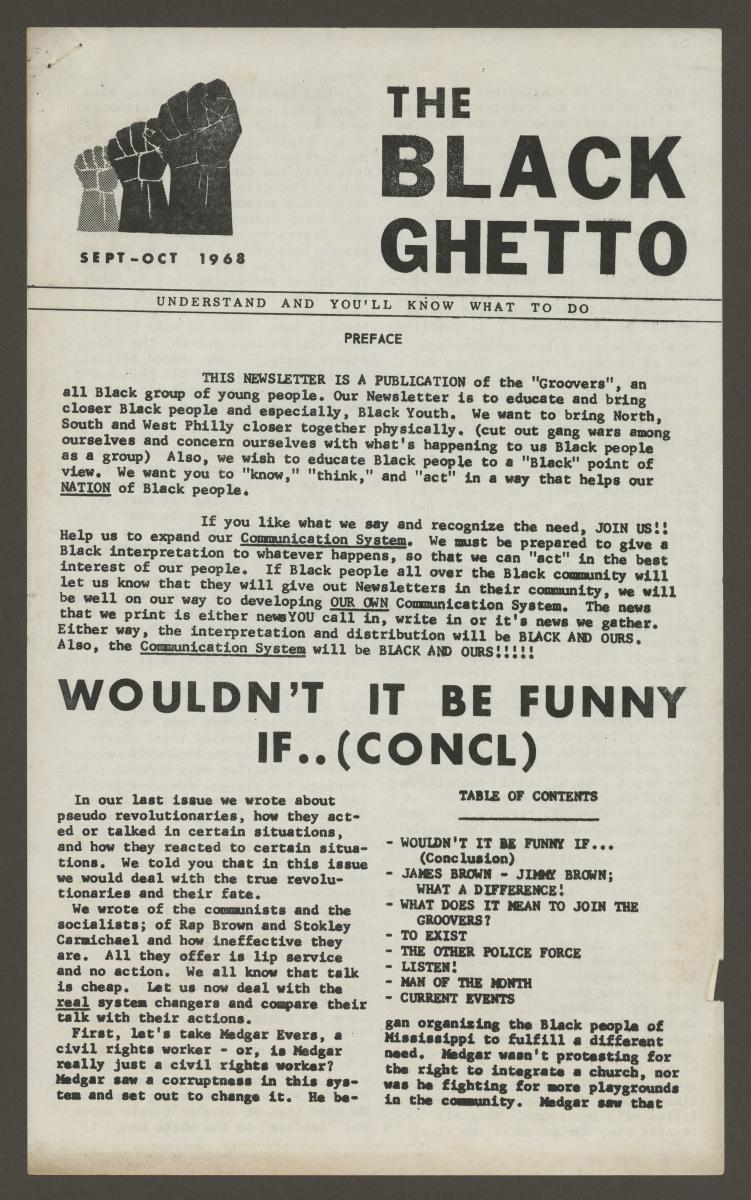

The Black Ghetto was a newsletter created by young black folks in Philadelphia who called themselves the “Groovers.” The goal of the newsletter was to bring people from different Philadelphia neighborhoods together in order to address problems facing the entire black community while eliminating gang violence. The Groovers also sought “to educate Black people to a ‘Black’ point of view.” Their newsletters included coverage of current events and issues concerning the black community. As part of this coverage, the Groovers regularly touched upon a number of themes including police brutality, institutional racism, and black identity.

The Black Ghetto front page, Sept-Oct 1968

The Black Ghetto is just one example of the many different student publications created in Philadelphia in the late 1960s. Creating and circulating newspapers was one way that black young adults in Philadelphia spoke out about their lives in that period. These publications gave them a chance to convey their experiences on their own terms and to communicate with each other and the general public. As the slogan of one such publication proclaimed, “say what we wanna say the way we wanna say it!!”

The Thelma McDaniel Collection at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania contains an impressive collection of student publications that gives a sense of the goals of young black Philadelphians and the ways that they imagined creating social change in the 1960s and 1970s.

“What would happen if the ‘gangs’ themselves took a stab at inner-city communications? What if they tried to put out a newspaper themselves? Dig it now. They did.” (Dig This Now, Vol. 1 No. 3 Monday July 21, 1969).

Dig This Now was a newspaper published by teenagers from “Francisville and the adjacent ghetto areas.” It received funding from the Urban Coalition of Temple University as well as from advertisements and paper sales (10 cents per copy or one year of 24 issues for $2.50). Dig This Now was largely a celebration of Black artists: it published poetry, short prose pieces, photos, and illustrations submitted by young people throughout Philadelphia. The paper also alerted readers to events in Philadelphia that showcased black artists, like a weeklong Black Arts Festival or a production of one of Lorraine Hansberry’s plays.

Another notable student publication from this time was Black Torch: The Voice of Black Students, a paper put out by students at Temple University. Black Torch regularly included news, information about upcoming events, and even a crossword puzzle. When Temple University proposed an expansion in the late 1960s that would displace a number of low-income black Philadelphians, Black Torch ran an impassioned article calling for black students to organize in opposition to the project. Each issue of Black Torch also included a short description of “the mother continent” of Africa since “No knowledge of the Black American is complete without knowledge of the mother continent as it stands today.” As with the other papers, this array of content was intended to engage young black Americans with questions of identity, community, and justice.

Black Ghetto, Dig This Now, and Black Torch are just a few samples among similar periodicals in the collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Some of the publications primarily covered hard news while others contained a more diverse array of written and visual work, but they shared a number of common goals: broadcasting black voices that were traditionally silenced by white power structures, mobilizing young black Philadelphians, and exploring questions of black identity and community in contemporary America. At their core, these newspapers allowed students to voice their concerns and stand up for what they believed in during a period of unrest and racial tension in Philadelphia.

Fifty years later, the racial discrimination of the late 1960s persists. Where young black Philadelphians once created newspapers and journals to address the wrongs they experienced, contemporary black Americans have capitalized upon social media as a tool for mobilization and expression. Hashtags, Twitter threads, and articles shared on Facebook have brought a unique set of benefits and challenges as a new generation attempts to confront systemic racial injustices.

References:

McDaniel, Thelma. Thelma McDaniel Collection. Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Though It Failed, the Treaty of Fort Pitt Was the First of Its Kind

Philadelphia N.O.W Motivates Women to Fight for Equality

By Gina Reitenauer, Intern from Syracuse University, and Nina Kegelman, C. Dallett Hemphill Undergraduate Intern of the McNeil Center for Early American History

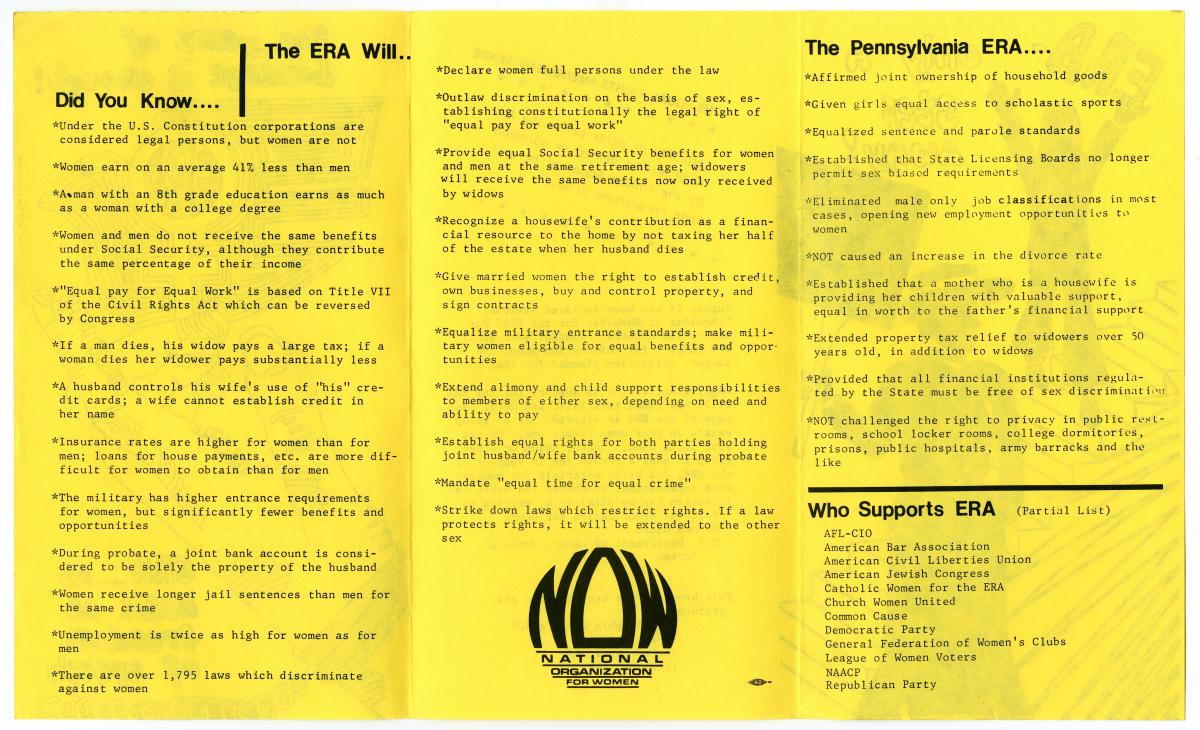

In 1966, a group of feminists established the National Organization for Women (N.O.W.) in order “to take action to bring women into full participation in the mainstream of American society now, exercising all the privileges and responsibilities thereof in truly equal partnership with men.” By the late 1960s, the Women’s Liberation Movement had spread across the country to cities such as Philadelphia, which became a seminal spot for feminist activism.

On January 11, 1968, Ernesta Ballard and former N.O.W. president Wilma Scott Heide founded the N.O.W. Philadelphia Chapter. Their primary objectives included adding the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to the Pennsylvania Constitution, repealing Pennsylvania’s abortion ban, and eradicating sex discrimination. Two organizational slogans captured the chapter’s aspirations of ERA ratification and securing reproductive rights: “We won’t be satisfied until the ERA’s ratified” and “Keep your laws off our bodies.” Philadelphia N.O.W. also spurred the creation of systems and networks that would support and empower women in the community.

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s “National Organization for Women: Philadelphia Chapter Records” documents the chapter’s activities between 1968-1977 through photographs, newsletters, articles, correspondence, posters, and pamphlets.

Philadelphia N.O.W. sent the largest delegation to the ERA ratification march in Washington D.C. in July 1978, and assisted other chapters in local ratification. A brochure about the benefits of the ERA states that ratification would “Declare women full persons under the law.” While the ERA was never ratified, HSP’s collection highlights N.O.W.’s impressive and persuasive efforts.

Posters in HSP’s collection show N.O.W.’s fight to remove limitations on abortion and hold rapists accountable. Proclaiming “Our bodies, our lives, our right to decide!” and “Sisters Unite, Disarm Rapists!”, these posters demonstrate the organization’s commitment to gender equality by promoting women’s physical agency. Records show that the chapter created a full network of support by providing mental health counseling, divorce referral forms, and listing sexual assault crisis lines.

Philadelphia N.O.W. increased access to childcare, education, employment opportunities, and support systems that enabled women to engage with their community as men did. One of the local organization’s most impressive achievements, ensuring the official preclusion of job listings separated by gender in Philadelphia newspapers, came in 1973. The N.O.W. Newsletter advertised “underground childcare services” for working mothers and promoted groups like the Society of Women Engineers that positioned women to gain work experience and mentoring.

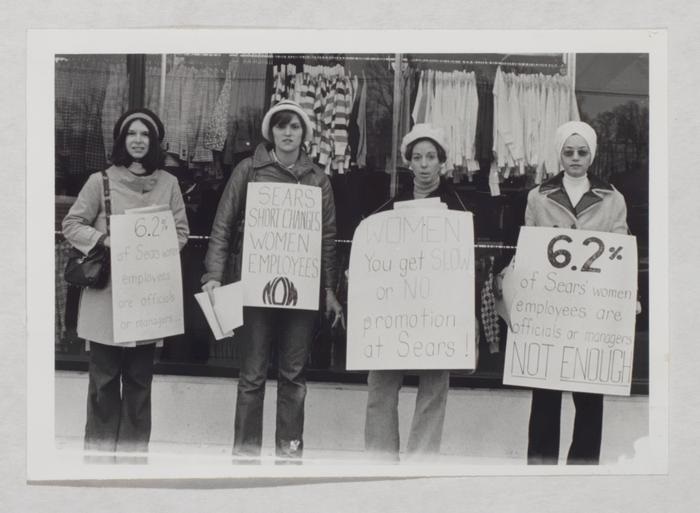

Women protest outside Sears over employment issues (no date).

The chapter was unafraid to call out companies and individuals who criticized or obstructed their feminist goals by putting them on a “Not Now List.” They also hosted “The Barefoot and Pregnant Award,” an ironic means of “honoring” someone who deliberately thwarted women’s rights. Remarks from a Barefoot and Pregnant Award Ceremony are in HSP’s collection. These tongue-in-cheek style designations perhaps prefigured the ways women confront sexism today, often taking to Twitter in order to belittle perpetrators of sexual assault or harassment.

By encouraging women to take matters into their own hands, stand up to sexism, and engage politically, NOW has played a significant role advancing legal and societal changes in favor of women’s rights. However, many of the same issues—poverty, lack of healthcare and childcare, sexual assault and harassment, threats to reproductive rights and LGBTQ rights, and negative media representation—that appear in the Philadelphia Chapter records still affect women today. Recently, worldwide women’s marches, political participation in record numbers, artistic activism, and increased intersectionality all combat gender discrimination, giving more attention to factors such as race, class, sexuality, and ability.

As we revisit the Women’s Liberation Movement during the 50th anniversary of 1968—its pivotal year—HSP’s collection of N.O.W. Philadelphia Chapter records provides interesting insight into the history feminism in the United States and the evolving debates on the subject of women’s rights.

References:

Toll, Jean Barth and Mildred S. Gillam, ed. Invisible Philadelphia: Community through Voluntary Organizations. Philadelphia: Atwater Kent Museum, 1995.

National Organization for Women. Philadelphia Chapter Records (Collection 2054), The Historical Society of Pennsylvania.