Philadelphians, Chinese, and Chinese Philadelphians: Narrating First Encounters

Following independence from Great Britain, it became especially important for America to create ties to the rest of the world that had previously not been necessary under British rule. Demand for commodities like tea, porcelain, and silk meant that American merchants had to quickly find a way to establish trade routes with China directly. Along with New York and Boston, Philadelphia became a key city from which vessels like the one shown below departed for Canton (now Guangzhou).

Detail of a watercolor painted by Jacob Peterson capturing the Helvetius, a ship belonging to Stephen Girard used in trade with India and China. This image was captured from Philadelphians and the China Trade 1784-1844 by Jean Gordon Lee found in HSP’s collection.

I decided to start my research by examining the different materials available at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania connected to the China trade, and from those materials, I was able to piece together a rough outline of what a voyage on such a scale would look like.

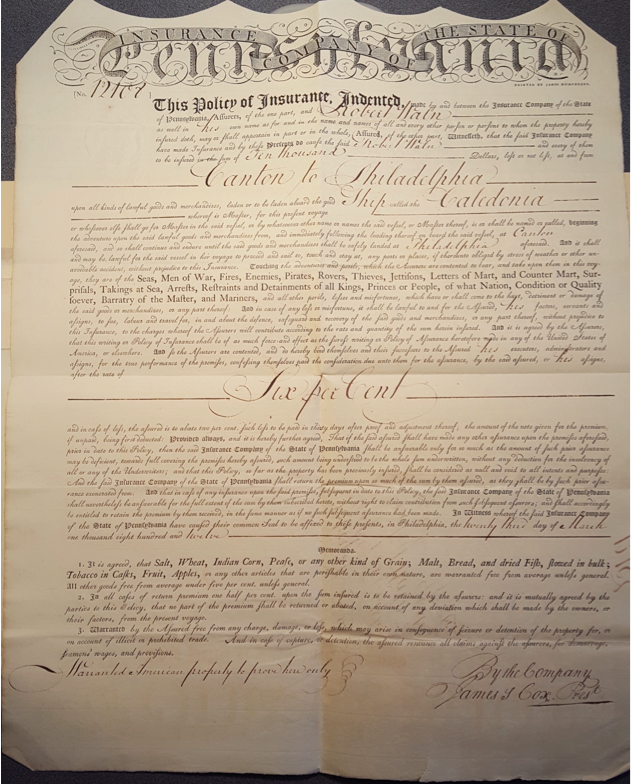

This insurance policy for the Calcedonia’s trip from Philadelphia to Canton and back is dated March 23, 1812. From the Robert Waln papers.

Within the Robert Waln Papers, I found a series of insurance policies for his ship, the Calcedonia, that was bound for Canton. From what I can make of the script, “the Assurers are contented to bear, and take upon them in this voyage… Seas, Men of War, Fires, Enemies, Pirates, Rovers, Thieves, Jettisons, Letters of Mart, and Counter Mart, Surprisals, Takings at Sea, Arrests, Restraints and Detainments of all Kings, Princes or People, of what Nation, Condition, or Quality soever, Barratry of the Master, and Mariners, and all other perils, losses and misfortunes, which have or shall come to the hurt, detriment, or damage of the said goods or merchandises, or any part thereof.” This appears to be quite a comprehensive list, and I have little doubt of its necessity, especially given the amount of risk associated with such a voyage.

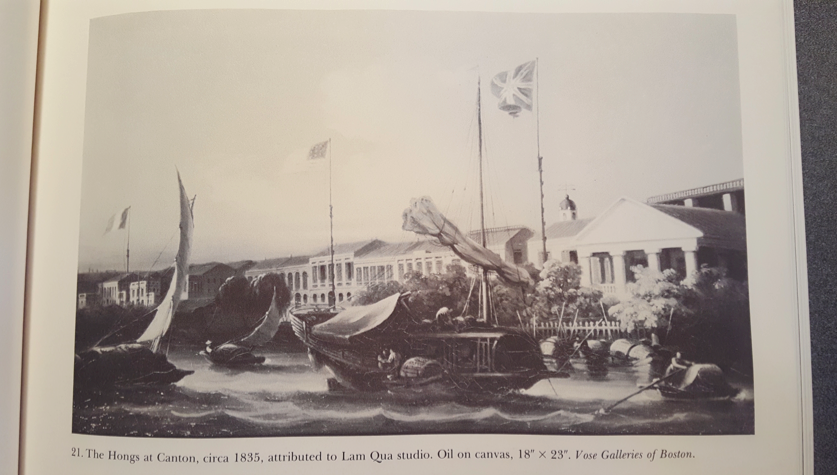

A detail from Carl Crossman’s The China Trade; Export Paintings, Furniture, Silver & Other Objects depicting a painting of the Hongs at Canton.

With all of the necessary documents in order, a ship traveling from Philadelphia to Canton would then undergo a voyage lasting several weeks before finally arriving at the mouth of the Pearl River. There at the Whampoa checkpoint, merchants would secure a translator and stock up on necessary supplies before being conveyed up the river to Canton. From there, business could commence.

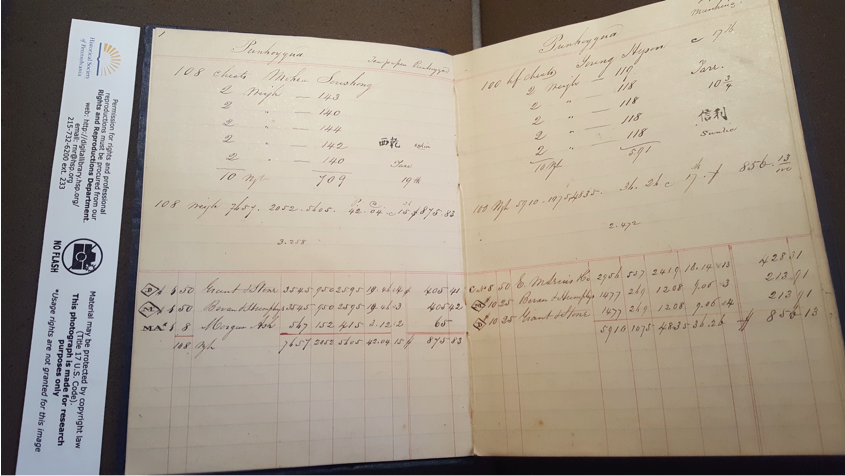

A “Tea Weighing Book” I found in HSP’s collection belonging to an anonymous merchant. On the left page is a tally of the prices for “Bohea Souchong,” a black tea from Fujian province, while on the right is a tally for “Young Hyson,” a green tea from Anhui province. The Chinese characters found on both most probably refer to the company from which the teas were purchased, and the heading “Punhoyqua” most probably refers to the name of the Co-Hong merchant with which this transaction took place.

Among the letters of another Philadelphia merchant, Joseph Archer, I found a narration of what sorts of struggles came with that sort of business. In a letter from Canton dated October 24, 1833 addressed to his “dear friend” Jon Cryder Esq. in London, Archer writes that:

“All sales are made here at the risk of the consignee. I know of no instance of guarantee on the part of the seller. Under the old system of doing business in Canton where all the sales and investments or nearly so were made through the Hong Investments, very little or no risk was incurred, but of late years the system of doing business has undergone a very decided change for the worse in this respect. The few men… who are now members of the Hong have confined themselves for several years back, almost exclusively to the Company’s business and sales are now necessarily made to the [proofer?] Hong merchants and to another clap of men who are termed Outside Merchants and who are doing business under the Hong Merchants, as [Jurors?] or Clerks. Some of these men are respectable and [possess?] some property; but the system is entirely illegal and in case of death or fraud of the party, you have no redress whatever under the law of China."

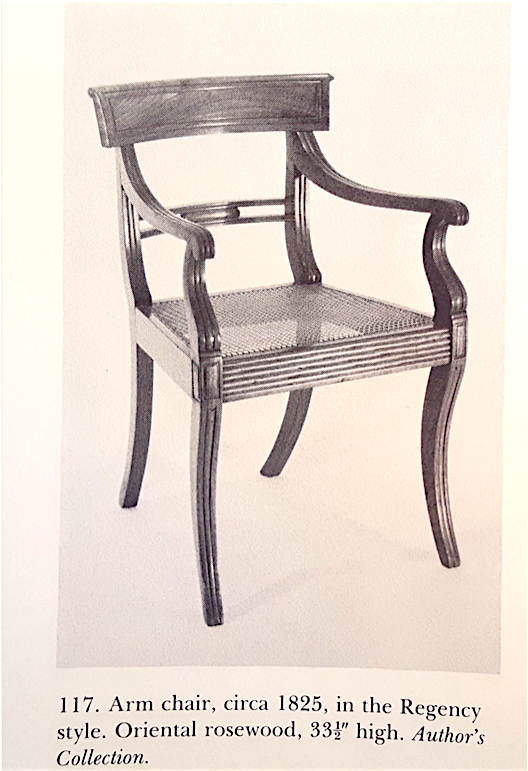

A detail from Carl Crossman’s The China Trade depicting a wooden chair made in China.

Archer continued: "In case of failure of any of the Hong Merchants, the Co. Hong is liable for all debts due to foreigners (of this you are no doubt aware) but the manner in which such debts are paid, in installments of 12 or 10 pct. per annum, amounts at last to almost a total loss...

"The Old Hong Merchants deny altogether being responsible for the debts of those who were appointed at the requisition of the Company [34?] years ago and subsequently. This is a question yet to be decided by the legal authorities; the foreigners contend that they are one and all members of the Co. Hong and are individually and collectively liable for each other’s debts.”

Detail from Ellen Decker’s After the Chinese Taste: China's Influence in America 1750-1930, a book in HSP’s collections. Shown here is a chest of drawers with details of fantastical creatures and scenery from China. Imports like these were the majority of what informed the public about Chinese culture.

Joseph Archer’s letter book, being the very first item I examined during my research, was more puzzling than enlightening at the time, especially with regards to the mentioned Hong and Co-Hong merchants. It was only after further inquiry from some secondary sources I examined at HSP that I was able to understand what it was Archer was referring to. During the Qing Dynasty, permission for foreign trade was only granted to a few merchants in Canton known as Co-Hongs, and foreign traders would conduct transactions and limit their activities to their country’s respective “Hong.” Thus armed with this knowledge, what Archer describes to his friend in this letter here is actually quite exciting—these “Outside Merchants” who operate underneath the Hong merchants are actually working illegally, and thus the Co-Hongs are technically not liable for the debts that their agents incur… a potentially disastrous situation for the unlucky foreigner.

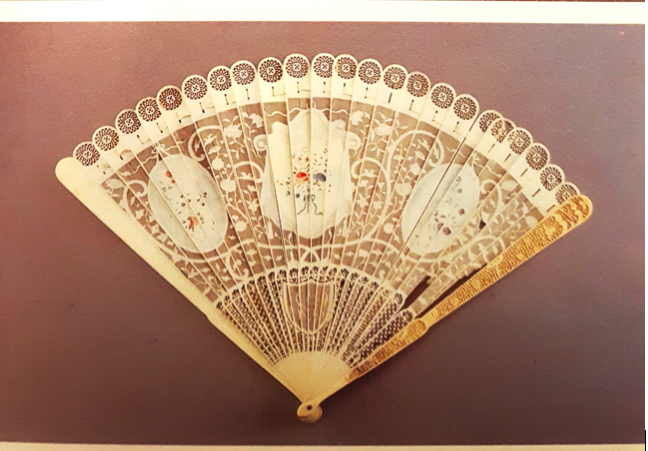

A detail from Jean Gordon Lee’s Philadelphians and the China Trade, 1784-1844 as found in HSP’s collection. This silk fan is one of the many imports from China that Philadelphians would have purchased.

However say that all does go well during these transactions. Having obtained the tea, silk, furniture, fans, and other goods, next comes the voyage back to Philadelphia. There, products from China were sold as exotic luxuries to the ladies and gentlemen who could afford them.

A detail from Carl Crossman’s The China Trade depicting samples of silk that could be imported.

But just as their knowledge of China is incomplete and obtained only from limited accounts and the objects they have purchased, my quick recount of the China trade is also imperfect. As the passage from Joseph Archer’s letter reveals, many obstacles to conducting trade presented themselves in the form of cultural and systemic disparities, and very little of what I looked at offers a glimpse at the lasting impacts of the China trade on the people of Canton. Perhaps some more digging through the HSP archives might remedy that…

Join me next time as I look at the founding of Philadelphia’s Chinatown and the first stirrings of Chinese American activism!

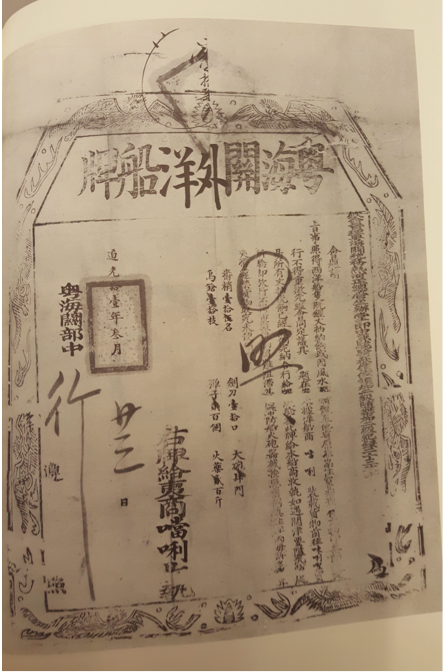

A detail from Carl Crossman’s The China Trade. Above is a certificate granting permission for a vessel to leave Canton.