Over the past few years, mustaches and beards have made a comeback as the must-have facial hair accessory. Handlebar, English, Walrus, and Imperial mustaches, to name a few, grace the faces of men young and old on today’s streets and screens. However, many of these facial accessories pale in comparison to the hirsute men of the Historical Society of Frankford. Within their collections, one can find some truly inspiring mustachioed and bearded men. Organized in 1905 and chartered in 1920, The Historical Society of Frankford is located in the Frankford neighborhood of Northeast Philadelphia. Their mission is to “collect, preserve, and present the history of Northeast Philadelphia and the region.”

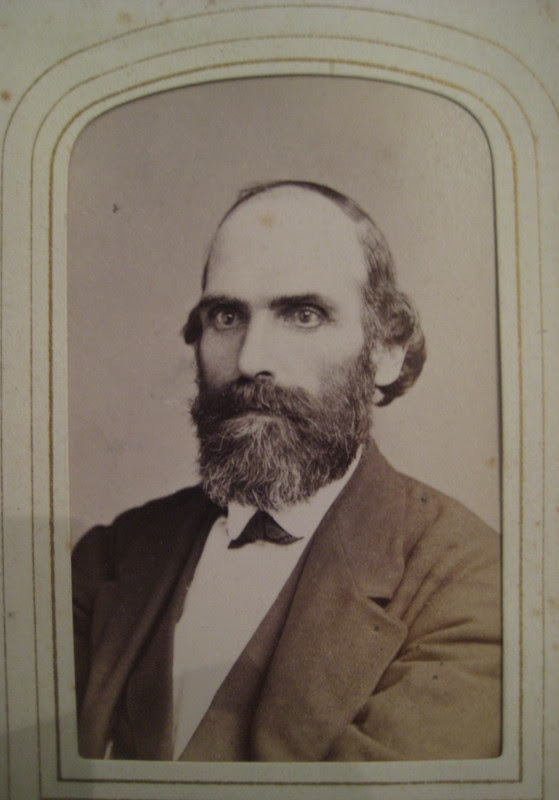

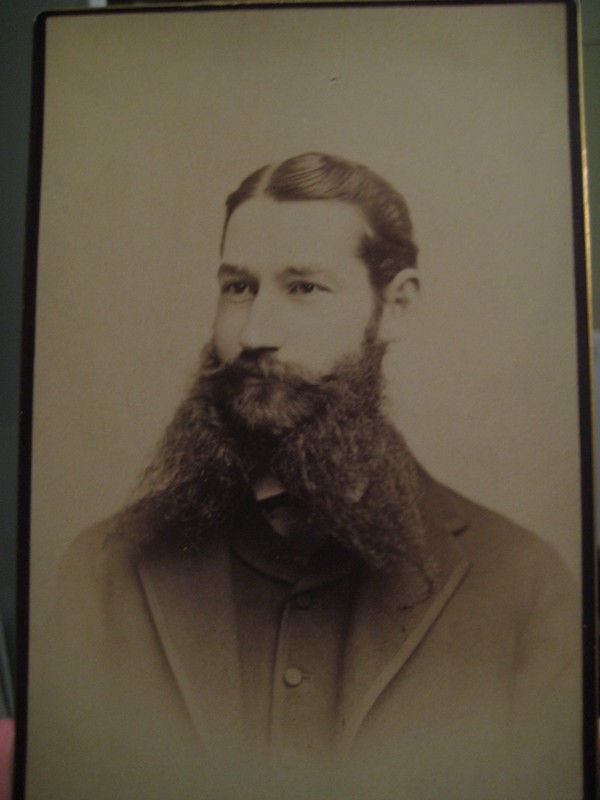

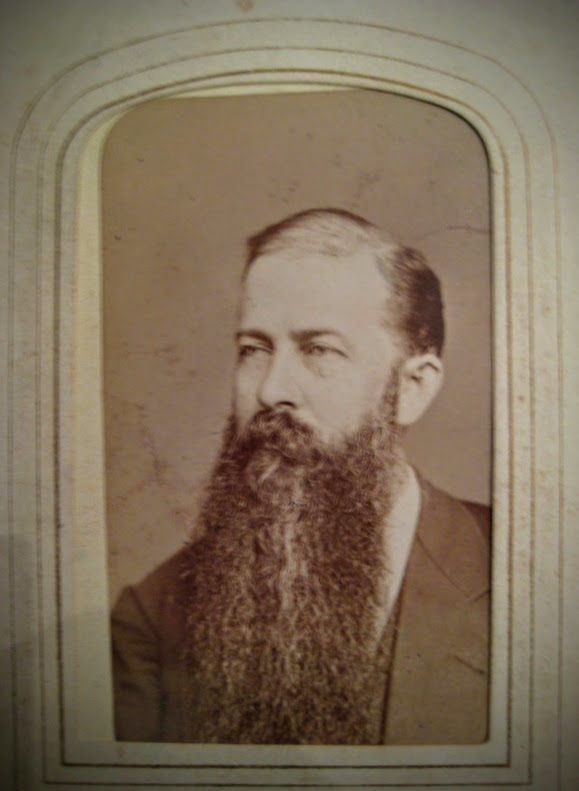

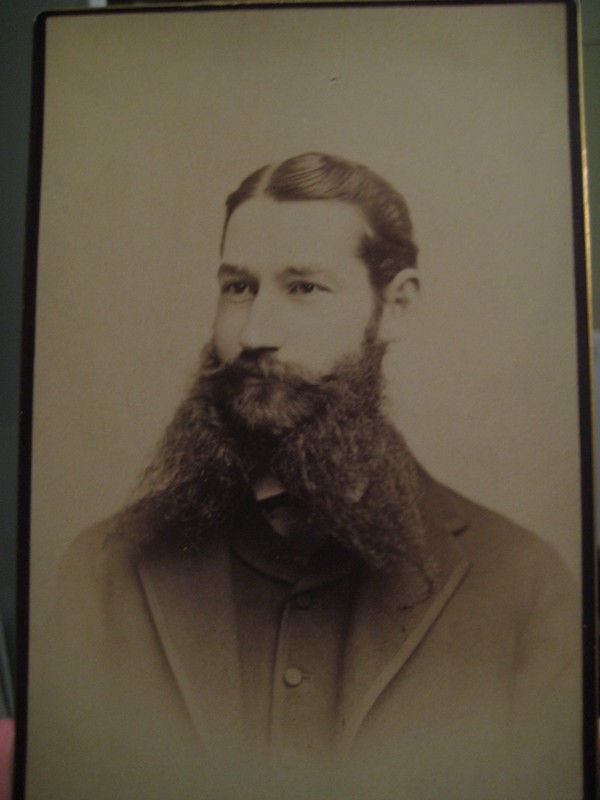

Take, for example, this gentleman. In addition to the stylish length, the streak of grey hair shows a level of confidence in his appearance and compliments his balding head.

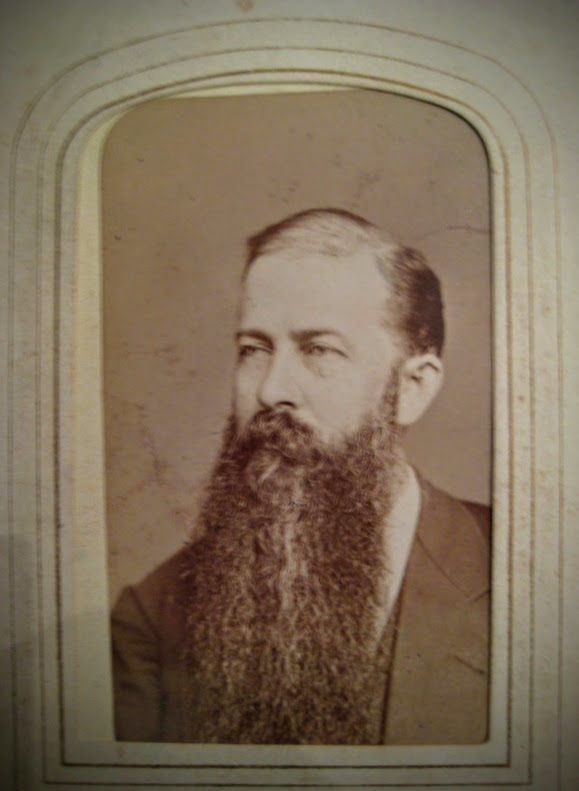

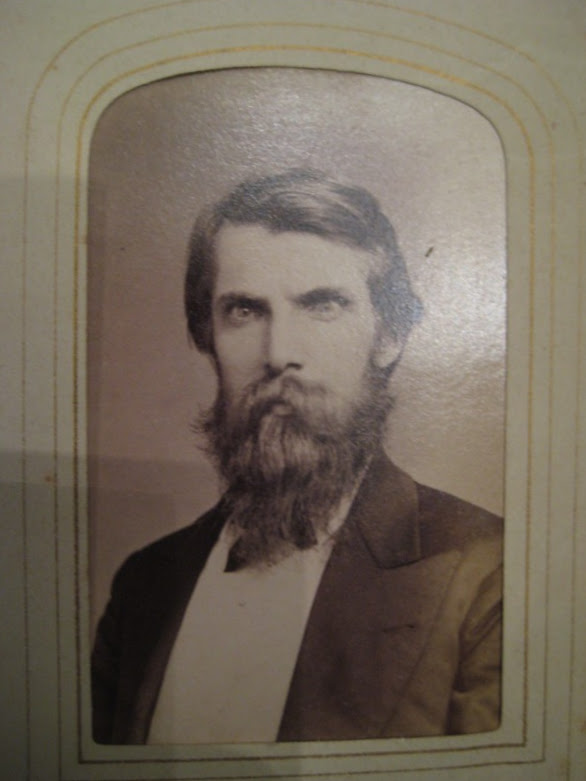

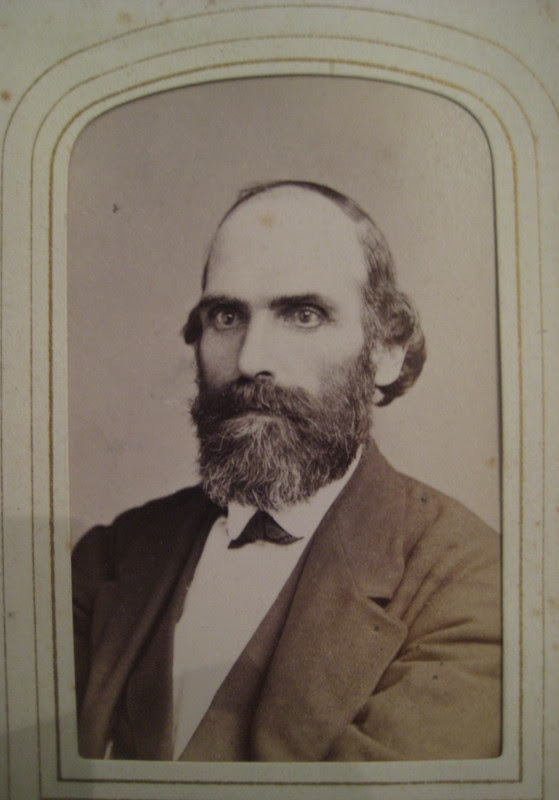

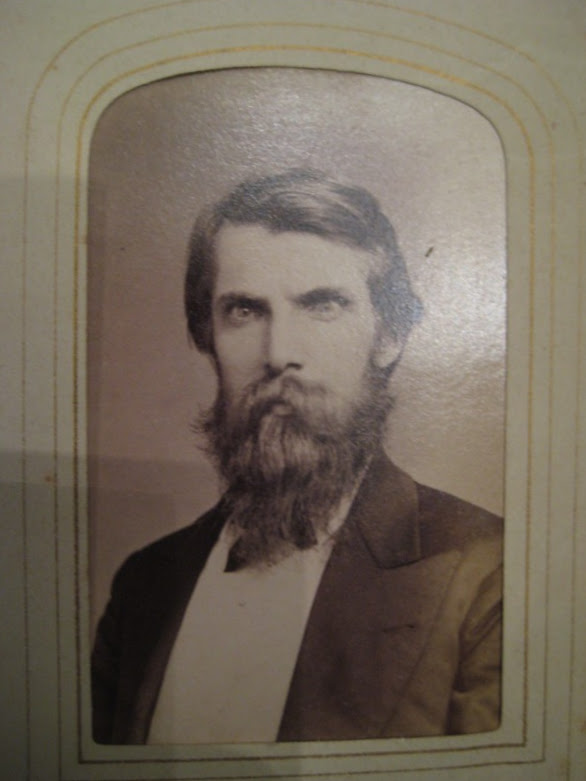

He can be found in one of the many family photograph albums from the late 18th and early 19th centuries held by the Historical Society of Frankford. Although many of the individuals in these albums are not identified by name, their noble beards and mustaches make them stand out as fashionable men of their time. Here are a few more notable facial accessories from the family photograph albums:

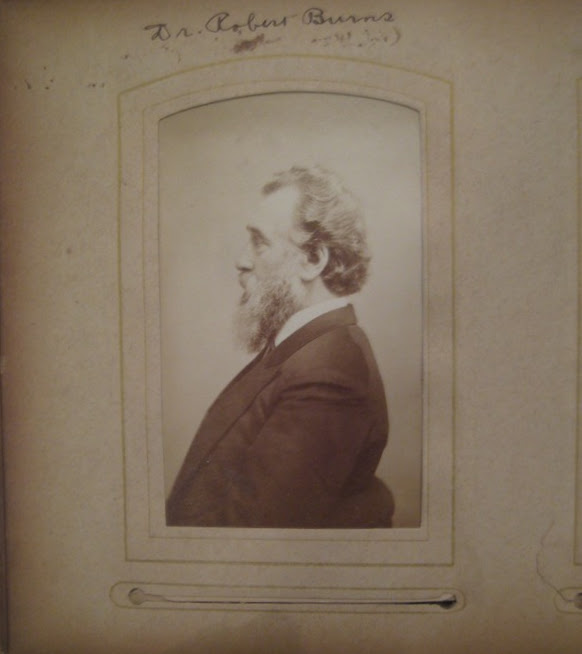

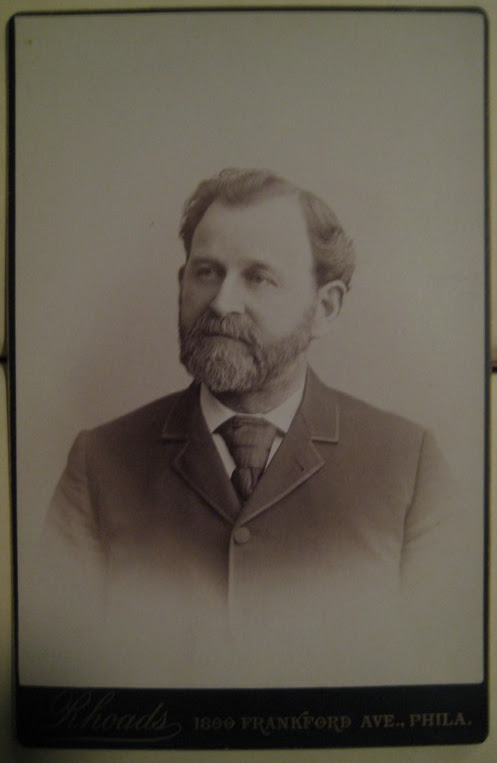

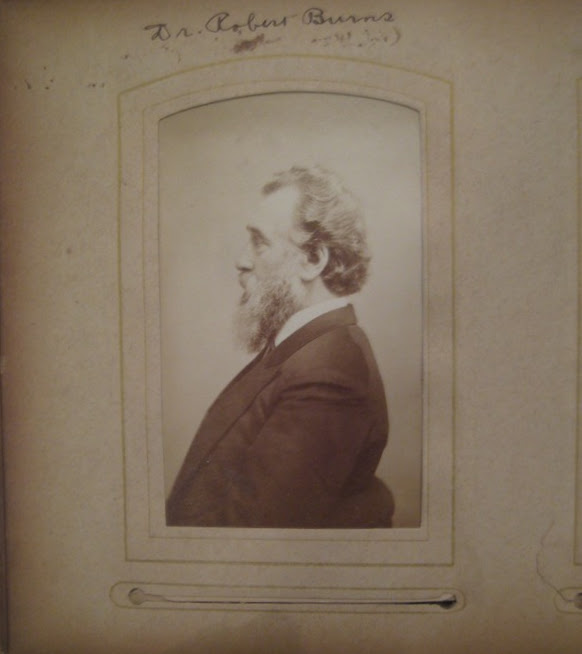

The Historical Society of Frankford’s collections also include several photograph collections such as the Lincoln Cartledge photograph collection, the T. Comly Hunter photograph collection, the Guernsey Hallowell photograph collection, and collections of cabinet cards and daguerreotypes, to name a few. The gentleman below can be found in the Society’s cabinet card collection.

This oversized photograph found in the records of Frankford Hospital captures a moment on one of the floors of the hospital. Unfortunately, the lighting made it difficult for the photographer to capture the gentleman in the wheelchair – resulting in an artistic interpretation of the missing man, mustache included. Although he may not have sported such a fine mustache, it clearly adds to the image.

Nearly half of the Frankford Cricket Club Cricket Team boasts bushy mustaches, most likely to help them become more aerodynamic as they run between wickets. Here, they are photographed at the Halifax Cup, a Cricket tournament that still takes place today in Philadelphia. Even though they lost (beat by Germantown Cricket Club), Team Captain William W. Foulkrod (front row, center) had the highest batting average for the team and fourth highest overall for the Cup. It must have been the mustache!

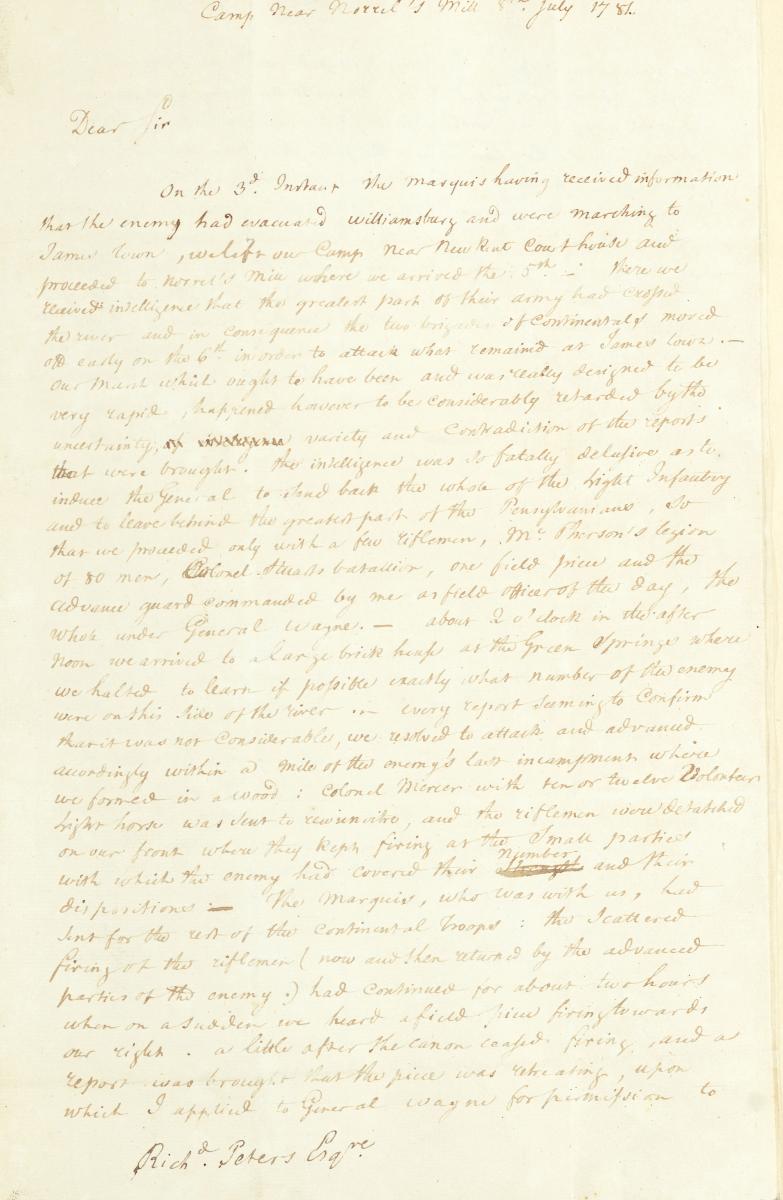

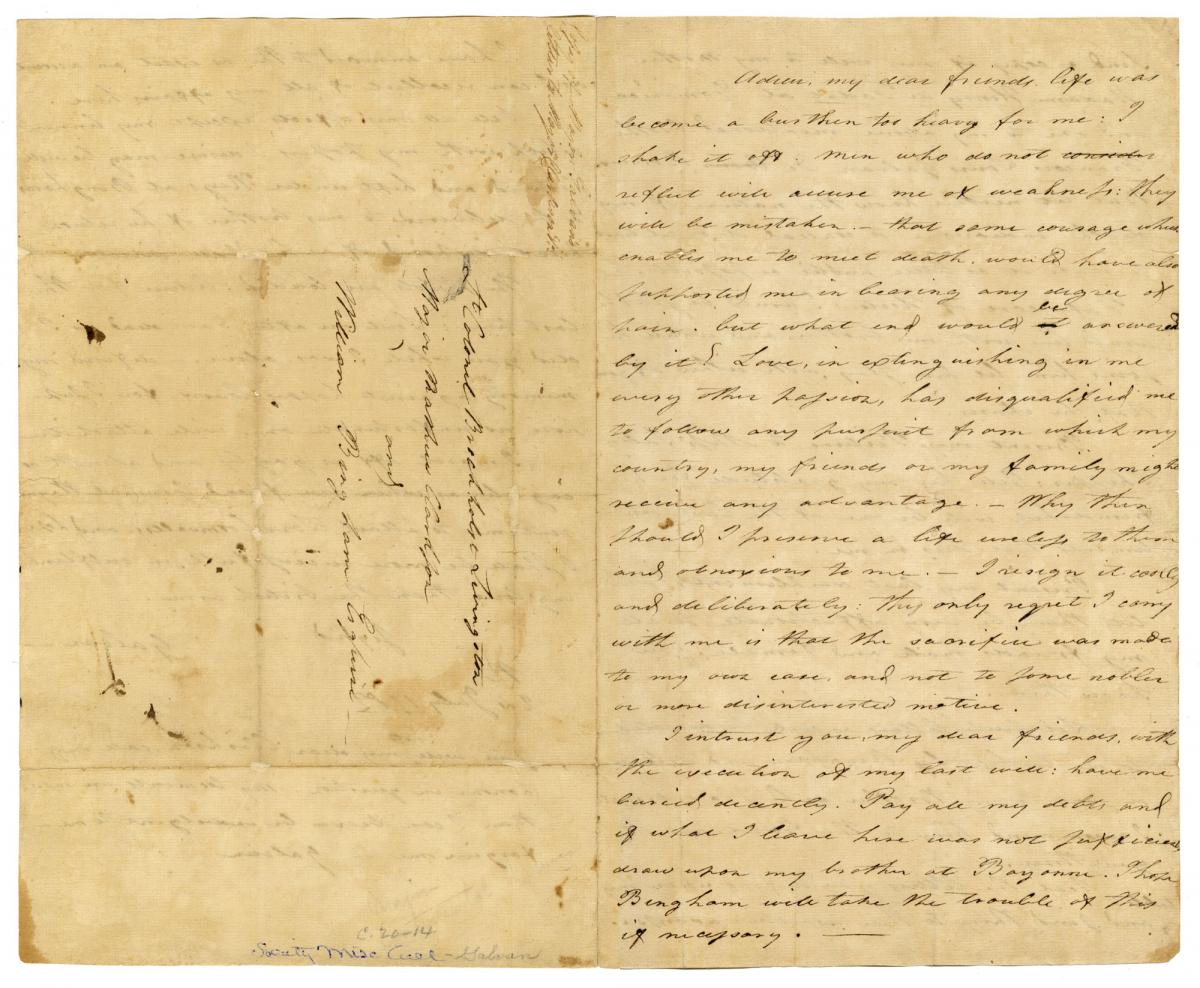

Special mention must be made for the beard of Abraham Lincoln, found in multiple states throughout the J. Friend Lodge Collection. Donated to the Historical Society of Frankford upon the death of John Friend Lodge, it is an extensive collection of books, articles, manuscripts, photographs, and autograph books relating to the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln, and Americana.

In addition to serving as an excellent collection documenting the state of Abraham Lincoln’s facial hair, it offers an extensive source of published material about the life of Lincoln. The impressive autograph collection also includes the signatures of notable military figures, politicians (including presidents), and authors such as Ulysses Grant, General George Meade, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Theodore Roosevelt, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Walt Whitman.

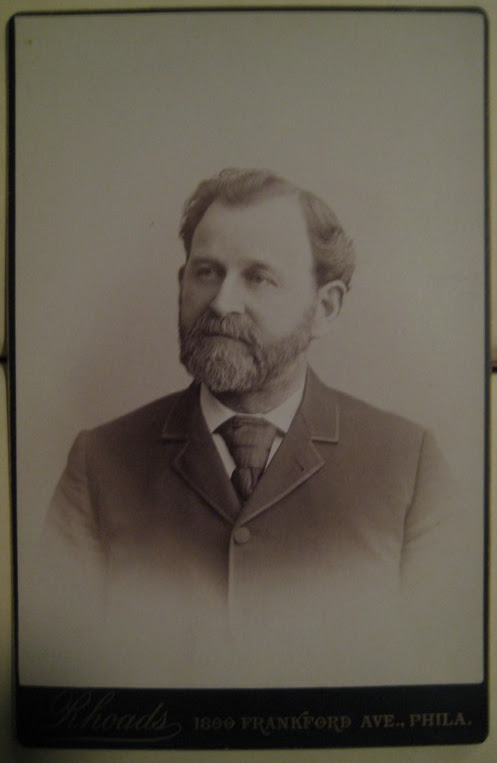

The Tomlinson, Peters, and Foehr Papers contain a variety of materials, a majority of which document the Tomlinson family, the Peters and Foehrs having married into the Tomlinson family. Dr. Jonas T. Peters, photographed here with an amazing French fork beard, was the younger brother of Mary R. Peters, who married Thomas Pierson Tomlinson.

Dr. Peters worked as a dentist in Norristown, PA. Surely, his patients must have appreciated his robust facial hair!

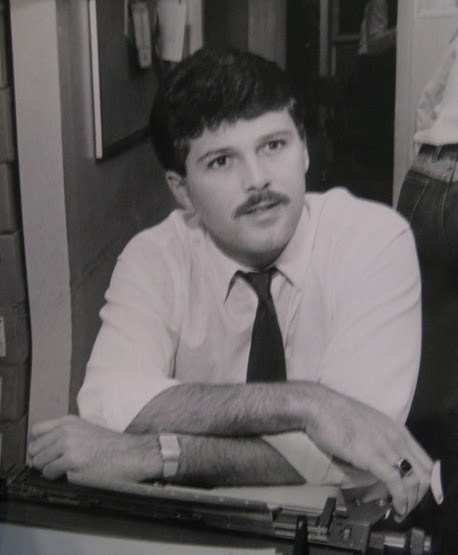

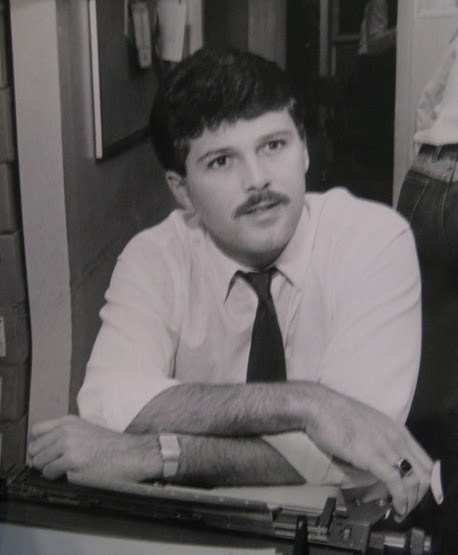

Of course, moustaches were not only found in late 18th century and early 19th century photographs at Frankford. The News Gleaner records at the Historical Society of Frankford include a large collection of photographs from the newspaper’s run, including this great shot of Lou Tilley, anchor at KYW TV3 in the 1980s and 90s.

Unfortunately, he no longer has this marvelous moustache.

Of course, there is much more to the Historical Society of Frankford than just beards and mustaches. In addition to preserving examples of glorious facial hair, the Historical Society of Frankford documents significant people, places, and organizations of the Northeast. Noteworthy collections not mentioned here include the Wright’s Industrial and Beneficial Institute records, the Magarie Andrews Smith papers, the Yellow Jackets football team (precursor to the Philadelphia Eagles) collection, and an extensive collection of deeds, to name a few.

Take a visit to the Historical Society of Frankford to learn more about the history of Philadelphia, the Northeast, and Frankford!