The Village Improvement Association of Doylestown

In 1895, a group of fourteen women in Bucks County, Pennsylvania joined together to improve the quality of life in their community, forming the Village Improvement Association (VIA). Twenty-eight years later in 1923, the same group founded the Doylestown Hospital. Today, the Village Improvement Association of Doylestown is over 120 years old, has over three hundred and fifty members, host annual fundraisers, oversees a retirement community in addition to Doylestown Hospital, and continues to support projects improving the quality of life in Bucks County.

The VIA is an extraordinary group of women and is the only women’s club in the nation to own and operate a hospital. In addition to all that they do to improve the community of Bucks County, the VIA owns and maintains the James-Lorah Memorial Home, which also serves as their headquarters.

The James-Lorah Memorial Home is a 17-room Federal style building located on North Main Street in Doylestown, PA. The building was the home to Miss Sarah M. James, a charter member of the Village Improvement Association in 1895, and was bequeathed to the VIA in 1954 upon her death, including the home’s contents and a trust fund for its maintenance.

The house itself has a fascinating history. The north wing of the home was originally a saddler’s shop, built in the early 1800s. In 1824, the building was purchased by Abraham Chapman and gifted to his grandson, Henry, who used the property as his law office. In 1884, Henry expanded the building by adding the main section of the house. Noted historian and archaeologist Henry Chapman Mercer was born in one of the bedrooms in 1856.

In 1869, the home was purchased by Dr. Oliver P. James, a physician. Dr. James resided there with his wife, Sara Gordon James, son Oliver, and two daughters, Martha and Sarah. In 1896, Martha married the Reverend Dr. George H. Lorah, a Methodist minister. The house became the summer home of Sarah James and the Lorahs following the deaths of Dr. and Mrs. James and their son Oliver. When Martha Lorah passed unexpectedly in 1918, Sarah James and Dr. George Lorah received a special dispensation from the Methodist church to continue living together as brother and sister-in-law.

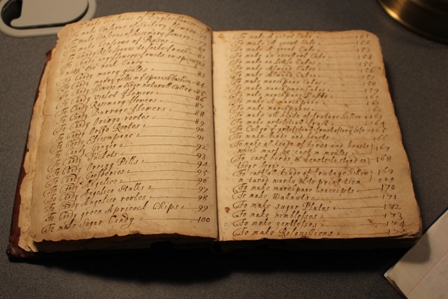

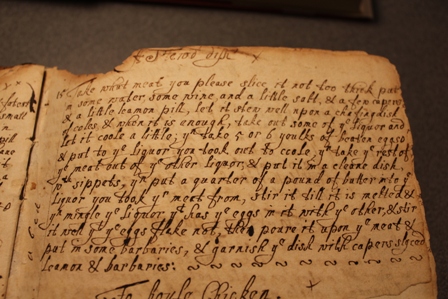

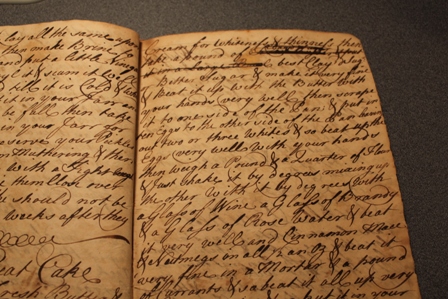

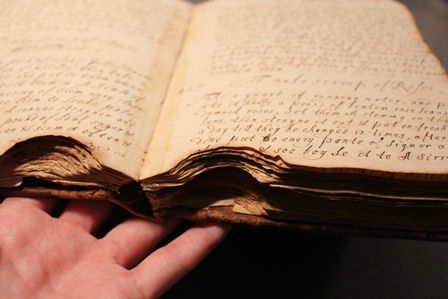

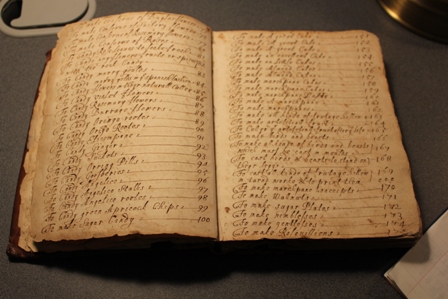

The James-Lorah Home provides a unique glimpse into the lives of the James and Lorah families. The home contents bequeathed to the VIA included not only the furnishings, but also books, papers, memorabilia, and ephemera amassed over the years by the James and Lorahs.

Dr. George Lorah, in addition to being a Methodist Minister, was an avid poet. The collections at the James-Lorah Home include many of his handwritten poems, as well as clippings of poems from his church’s publication, “The Green Street Banner.”

The Bogie Man, written by Dr. George Lorah

One of a few albums in the collection, From Over the Sea, consists of pressed flowers and fauna from travels abroad by Sarah, Martha, and Dr. George. In addition to this album, there are pressed flowers that can be found elsewhere in the collections.

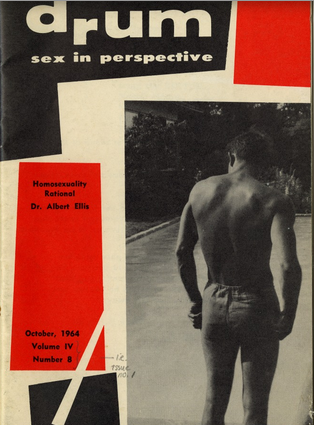

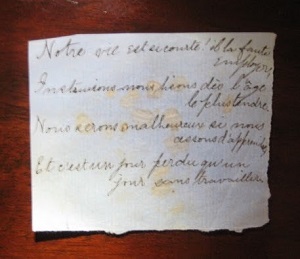

A rather unexpected find during our survey visit was the following note, tucked into a Bible in one of the bedrooms of the home.

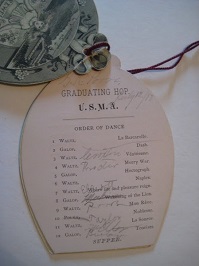

The collection also contains materials from Sarah and Martha’s youth, including several dance cards. Popular in the 19th century, dance cards were distributed to ladies attending formal dances and balls. Gentleman would choose the evening’s dance they wished to share with the lady, and sign his name next to it. The dance card below belonged to either Sarah or Martha, from the United States Military Academy (West Point) Graduation Hop in 1883.

The James-Lorah Memorial Home contains many more details of the lives of the James and Lorah families, as well as the Village Improvement Association of Doylestown. If you’re interested in learning more about the VIA or the James and Lorah families, contact the Village Improvement Association!